The Christian Origin of the Red Cross

Like so many institutions, organizations, and benevolent agencies, the Red Cross had its origin in the Christian Faith. As noted below in the brief thumbnail sketch, the Christian faith of banker and businessman, Henry Dunant, was the impetus behind the compassion that has been and continues to be extended to millions around the world. The warm Christian hearts of his parents touched their own community but flowed more intensely through their son to a deeply troubled and hurting world.Red CrossChristian Origin of the Red Cross

Article ContentsChristian Origin of the Red Cross

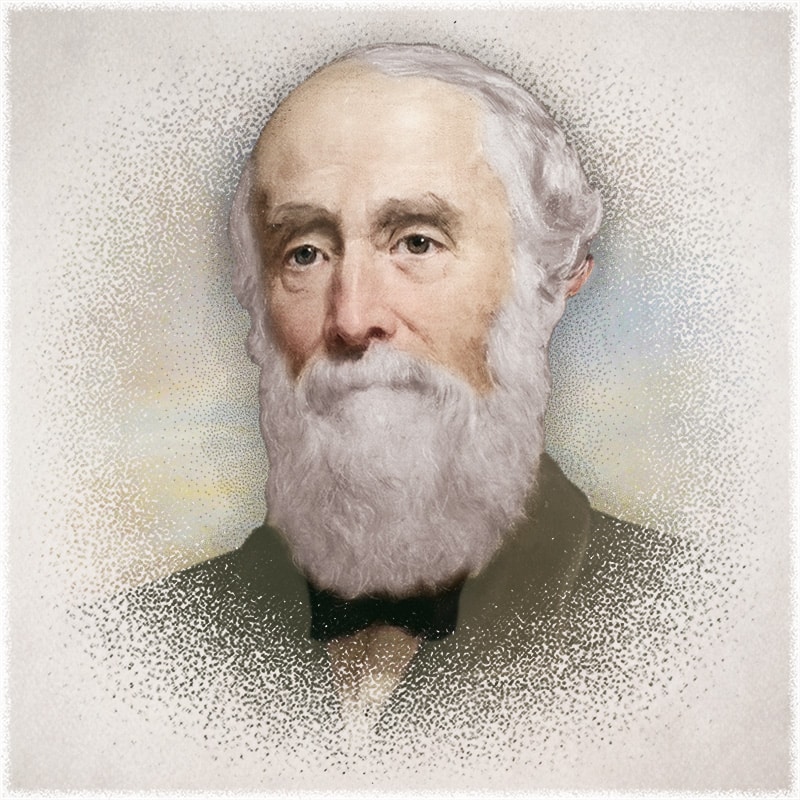

Jean Henri Dunant (May 8, 1828 - October 30, 1910), known to the world as Henry Dunant, was born in Geneva, Switzerland to a devout Christian Calvinistic family. Geneva had been the city where Protestant leader, John Calvin, had expended nearly all of his ministerial life. Though the followers of Protestant reformer, Huldrich Zwingli, and John Calvin joined forces in 1549 to become the Reformed Church, the system of theology that characterized this tradition has always been known as "Calvinism," and less commonly as "Reformed theology." The epicenter of Calvinism was the cradle in which Henry Dunant was raised.

His parents, Jean-Jacques Dunant and Antoinette Colladon Dunant, were individuals of significant influence in Geneva society. An obvious influence was exercised over Henry by his parents who were both engaged in social work—his father helping orphans and parolees through his work in a prison and orphanage, while his mother gave assistance to the sick and poor. These parental influences vividly impressed themselves upon young Henry and prepared him for the contributions he would make to the world.

In 1814, an evangelical revival (or Reveil) movement arose within the Swiss Reformed Church of Western Switzerland and Southern France. The influence of this revival continued to linger and, in time, came to exercise influence over the spiritual life of Henry. As is true of all vital Christianity, spiritual interests necessarily influence a believer's relationship to the world around him. It was also true for Henry, who at eighteen, joined the Geneva Society for Alms giving, and the following year, he and his friends formed the "Thursday Association" for the purpose of meeting together to study the Bible and help the poor, engaging also in visiting prisons and engaging in other social benevolent work. The breadth of his faith at this era of his life is reflected in a letter he addressed to the Protestant ministry of his area:

Dear Friends and Brothers,

A group of Christian young men has met together in Geneva to do reverence and worship to the Lord Jesus Whom they wish to serve and praise. They have heard that among you, too, there are brothers in Christ, young like themselves, who love their Redeemer and gather together that under His guidance, and through the reading of the Holy Scriptures, they may instruct themselves further. Being deeply edified thereby, they wish to unite with you in Christian friendship. Therefore, we hasten, dear brothers in Christ, although we do not have the happiness of knowing you personally, to assure you of our deep fraternal affection. We beg you to exchange correspondence with us in order to keep intact this Christian affection among the children of the same Father, that some of us may be profited to the greater glory of the Lord. We approach you, too, as a witness to the world that all the disciples of Jesus, who acknowledge and love Him before God as their sole refuge and sole righteousness, are no other than one great spiritual family whose members love one another sincerely, even though they be strangers, in the sign of the Dearly Beloved Who is their Guide, their Friend, their God and their Lord . . .[1]

Begins Career in Banking (1849)

One might suppose that a person like Henry who came to influence the lives of millions would have had few trials and struggles, but just the opposite is often true of those who have left a legacy for good. In 1849, at the age of 21, Dunant was forced to leave Calvin College because of his poor academic performance and begin an apprenticeship with the Lullin et Sautter Bank. After he successfully completed his apprenticeship, he remained on as an employee. This work was to open doors of future opportunity.

Initiates YMCA in Geneva (1852)

On November 30, 1852, Henry established the Geneva chapter of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). Only eight years earlier (June 6, 1844), a Christian draper, George Williams, opened the first YMCA in London for the purpose of improving "the spiritual condition of young men engaged in the drapery, embroidery, and other trades." Three years after Henry Dunant established the YMCA chapter in Geneva, he took part in the Paris conference that established the YMCA as an international organization. To this day, Henry Dunant remains one of the most influential individuals associated with the rise and progress of the YMCA.

The years that followed Dunant's initial relationship to the YMCA were some of the most important years in terms of preparation for that for which he would be remembered. In 1853, Dunant visited Algeria, Tunisia, and Sicily on business for a company devoted to the development of the "colonies of Setif". Successful in his business efforts, he wrote his first book titled, An Account of the Regency in Tunis (published in 1858). In 1856, he created the Financial and Industrial Company of Mons-Djemila Mills, an agricultural and trading company based in French-occupied Algeria. He had received a land grant but details concerning land and water rights had not been sufficiently clarified between Dunant and French colonial officials, and the authorities were uncooperative in resolving the issues. To clarify and resolve matters, Dunant proposed to take his concern directly to the French emperor, Napoleon III, who was at that time engaged in war in Lombardy. Napoleon was allied with the Piedmont-Sardinia forces against Austria, who had occupied much of modern-day Italy.

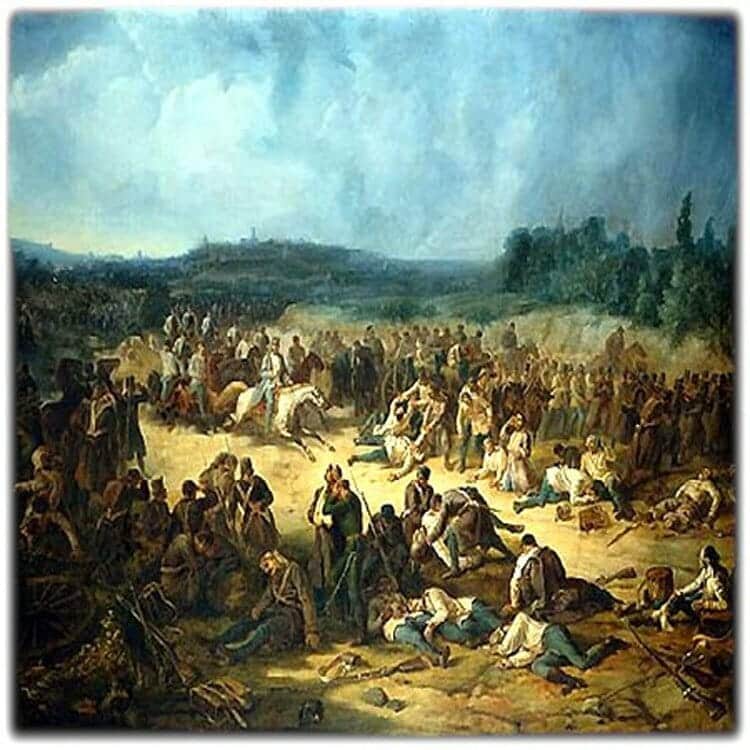

The Battle of Solferino (1859)

Napoleon had located his headquarters in the small town of Solferino (Italy), and it was there Dunant traveled to personally meet him. As he neared Solferino on the evening of June 24, 1859, he came upon the sight of thirty-eight thousand wounded, dying, and dead soldiers on the battlefield near Solferino. As many as 300,000 soldiers are believed to have fought in this battle that day-which was part of the Second Italian War of Independence. Horrified by the sight of such suffering, Dunant was deeply troubled that little or no effort was being made to tend the wounds of the soldiers and comfort the dying. In disbelief, he began to organize the civilian population, especially the women and girls of the town, to render aid to the wounded and dying. Helping to erect a makeshift hospital, he personally secured needed supplies and materials to render assistance to the mass of humanity—regardless of the political allegiances of the soldiers. To assist in his efforts, Dunant secured the release of Austrian doctors captured by the victorious Napoleon and his French forces.

A Book Begins the Red Cross (1862)

Returning to Geneva in early July, he penned a book concerning his experience, which he titled, A Memory of Solferino (Un Souvenir de Solferino, published in 1862). In it, he vividly depicted the battle and its tragic aftermath of suffering. The following extended quote is representative of his effort:

If a battalion is driven away another replaces it; each hill, each height, each rocky eminence becomes a theatre for an obstinate struggle.

On the heights, as Well as in the ravines, the dead lie piled up. The Austrians and the allied armies march one against the other, killing each other above the blood-covered corpses, butchering with gunshots, crushing each other's skulls or disemboweling with the sword or bayonet. No cessation in the conflict, no quarter given. The wounded are defending themselves to the last. It is butchery by madmen drunk with blood.

Sometimes the fighting becomes more terrible on account of the arrival of rushing, galloping cavalry. The horses, more compassionate than their riders, seek in vain to step over the victims of this butchery, but their iron hoofs crush the dead and dying. With the neighing of the horses are mingled blasphemies, cries of rage, shrieks of pain and despair.

The artillery, at full speed, follows the cavalry which has cut a way through the corpses and the wounded lying in confusion on the ground. A jaw-bone of one of these last is torn away; the head of another is battered in; the breast of a third is crushed. Limbs are broken and bruised; the field is covered with human remains; the earth is soaked with blood.[2]

Dunant distributed his work to many leading political and military figures in Europe with the hope that a neutral organization could be organized and established to provide care for wounded soldiers. His hope was soon to be realized.

To promote his idea, Dunant began to travel throughout Europe, but his strongest support was to come from his hometown. On February 9, 1863, at a meeting of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, Dunant's recommendations were examined, assessed by the members, and a five-person committee was established to further pursue and implement his ideas. Dunant was made one of its members. A few days later, on February 17, 1863, the selected five-person committee convened for the first time—the date the International Committee of the Red Cross regards as its founding. Later that same year, in October, fourteen nations took part in a conference organized by the committee to improve the care of wounded soldiers.

The Geneva Convention Follows (1864)

The natural result of the formation of the Red Cross was to seek universal compliance with humane treatment of soldiers during periods of war. Less than a year later after the first international meeting, on August 22, 1864, the Swiss Parliament convened a conference which resulted in the composition and signing of the First Geneva Convention. Dunant undertook the responsibility of the accommodations for the representatives of the twelve participating nations.

First Geneva Convention (1864)-concerned with sick and wounded armed forces;

Second Geneva Convention (1906)-assistance of sick and wounded armed naval forces;

Third Geneva Convention (1929)-concerned with treatment of prisoners of war;

Fourth Geneva Convention (1949)-concerned with protection of civilians during war.

The four Conventions are referred to as the "Geneva Conventions of 1949" or simply the "Geneva Conventions". They have been modified by three amendment protocols.

Protocol I (1977)-concerned with victims of international armed conflicts;

Protocol II (1977)-concerned with victims of non-international armed conflicts;

Protocol III (2005)-concerned additional distinctive emblem.

Out of the Christian heart of Henry Dunant was birthed, not one, but two great influences for good—the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention. As noted below, his efforts would result in a third influence that extended to the Muslim world.

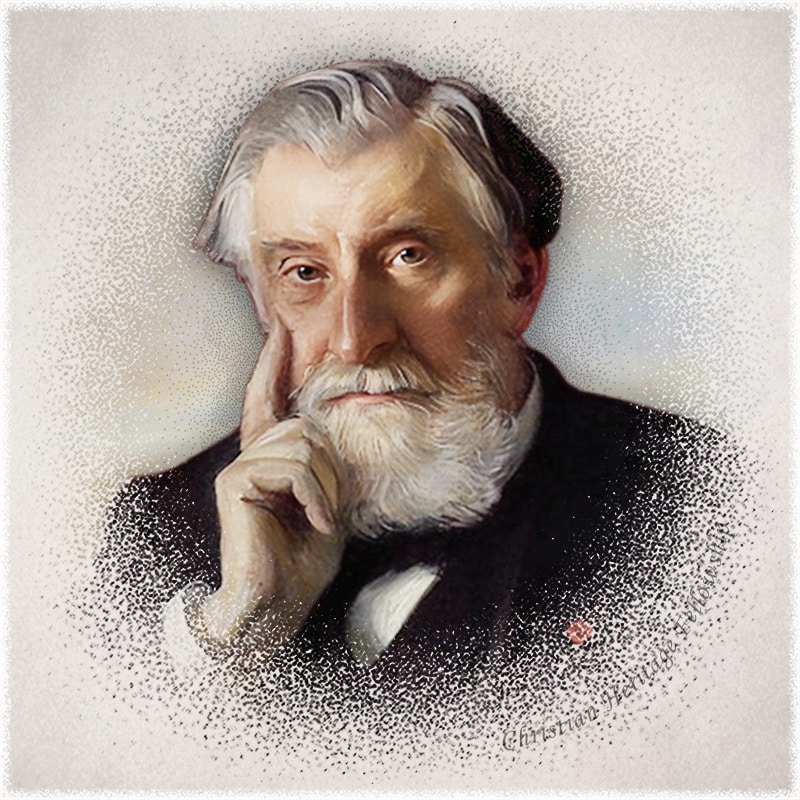

As a result of his humanitarian efforts, Dunant's business in Algeria suffered. Tragically, bankruptcy ensued, and family and friends who had invested in his ventures suffered loss along with him. In August 1867, Dunant resigned as Secretary of the International Committee of the Red Cross and in September withdrew completely from the Committee. Gustave Moynier, a member of the ICRC, who had rivaled Dunant for some time was responsible for much of the humiliation and rejection of Dunant from this time forward. From the inception of the ICRC, Moynier had resisted Dunant's leadership. Strangely, Moynier, who showed no compassion for Dunant, came to be the leader of the organization that best represented the compassion of Henry Dunant.

Dejected, Dunant left Geneva never to return, settling first in Paris where he was reduced to sleeping on park benches. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, he visited the wounded that were taken to Paris. Following the war, he travelled to London where he endeavored to organize a diplomatic conference addressing issues related to prisoners of war. The Russian Tsar encouraged him, but England was not receptive to his ideas.

Eventually Dunant began to receive modest support from a distant family member that enabled him to move to Heiden, Switzerland in 1887. Here he spent the remainder of his life, living in a hospital and nursing home after April 1892.

Return to Public Attention (1895)

For nearly thirty years, Henry Dunant was obscured from public attention. He never rose above the experience of bankruptcy and personal assaults of Moynier, but he was not to be entirely forgotten by the world. Return to the attention of Europe and the world was to be facilitated by Georg Baumberger, the chief editor of the St. Gall newspaper, Die Ost schweiz. In September 1895, Baumberger wrote an article on Dunant after having met and conversed with him in Heiden a month earlier. The article, "Henri Dunant, the Founder of the Red Cross," also appeared in a German magazine, Uber Land und Meer and was reprinted in other periodicals throughout Europe, resulting in revived attention from dignitaries throughout Europe, including a note from Pope Leo XIII. Gratitude was further expressed through awards and financial appreciation. The latter greatly improving his financial standing.

Receives First Nobel Peace Prize

After the memory of the work of Henry Dunant was revived throughout Europe, he continued to enjoy notoriety that was denied to him for so many years. Perhaps one of the greatest accolades was the bestowal of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 to Dunant and French pacifist Frederic Passy, founder of the Peace League. A bitter-sweet congratulations was offered by the International Committee of the Red Cross that read,

There is no man who more deserves this honor, for it was you, forty years ago, who set on foot the international organization for the relief of the wounded on the battlefield. Without you, the Red Cross, the supreme humanitarian achievement of the nineteenth century would probably have never been undertaken.[3]

Tragically, the end of Henry Dunant's life is reflective of what must have been his response to the betrayal of Gustave Moynier and family and friends. Toward the end of his life, he renounced Calvinism and became skeptical of life in general, at times insisting that the cook at the nursing home where he stayed taste the food in his presence to ensure that he would not be poisoned.

On October 30, 1910, Henry Dunant died after sending the Italian queen his biography written by a schoolteacher, Rudolf Muller. His final words were, "Where has humanity gone?" As a demonstration of its appreciation, the city of Heiden, where he spent his latter years, memorialized his life and service with the Henry Dunant Museum.

Few men have left a legacy of compassion exceeding or attaining the degree bequeathed to it by Henry Dunant. As the Father of the Red Cross and Geneva Convention, he was by default the impetus behind the Red Crescent of the Muslim world, and the YMCA will always claim him as one of their early luminaries. It was not atheism or agnosticism that conceived these institutions of compassion, and it was not Islam, Buddhism, or another world religion. In contemporary society, atheists and the irreligious are attempting to rehabilitate their public image, but irreligion cannot boast of a legacy of compassion and blessing. Likewise, other world religions are reflective of the cultures they have produced, and "Christian" nations bless the world to the degree they conform their cultures to the evangelical Gospel of Jesus Christ. As an evangelical, Henry Dunant was a stream of influence in the larger current for good which has flowed from the cross and person of Jesus Christ.

May God give the world more Henry Dunants raised in homes where moms and dads are examples of godly Christian living!

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Martin Gumpert, Dunant, The Story of the Red Cross (New York: Oxford University Press, 1938): 22.

[2] Henri Dunant, Origin of the Red Cross: "Un Souvenir de Solferino." Translated by Mrs. David H. Wright (Philadelphia, PA: The John C. Winston Co., 1911), 7-8.

[3] Wikipedia, " Henry Dunant" (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Dunant, June 21, 2013).