George Washington and the 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic

The year 1793 was one of the worst in history for the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It had been one of hottest and driest that folks in Philadelphia could ever remember. The dirty river stank unbearably, and the city was infested with swarms of flies and mosquitoes. Death laid its hand upon the city, making itself known first at the Arch Street Wharf.1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic

On August 19th, the plague that raged within the city was diagnosed by one of its doctors as yellow fever. For one hundred days and nights, the city was seized with the horrors of this plague. At this point, Philadelphia was the largest seaport in our young nation and was also its capitol. Both trade and the federal government were paralyzed. Many sought to leave the city, and those who remained were forced to care for the dead and dying. In the early weeks of the plague, victims were dying at a rate of seventeen a day, then twenty, and then forty. Not knowing the cause of the disease, doctors and citizens alike resorted to the use of ludicrous preventatives. But more died.1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic

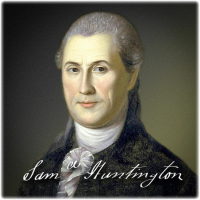

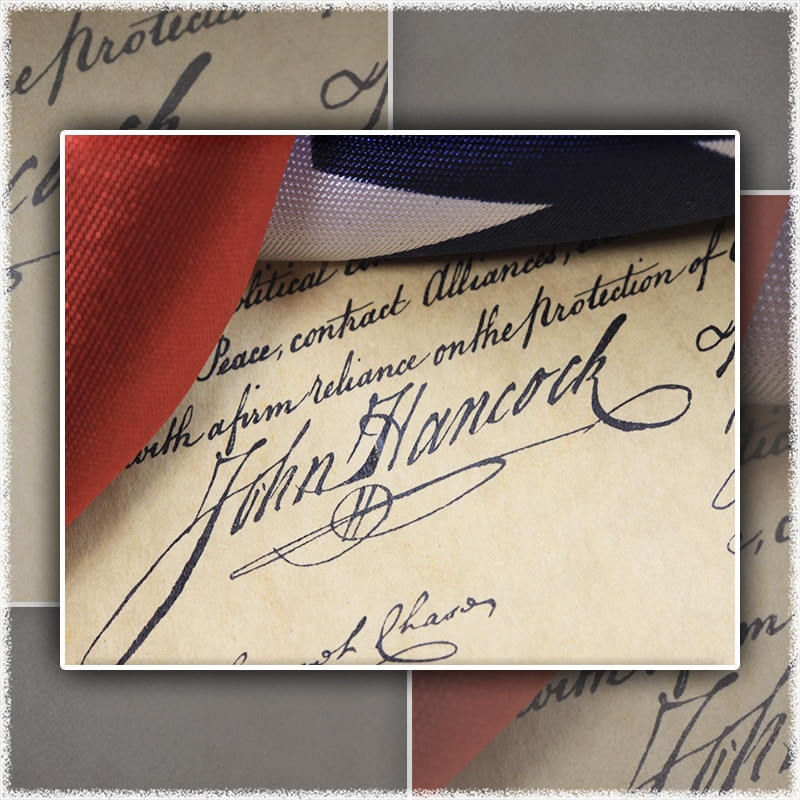

As the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 was laying its cold hand upon America's temporary capitol of Philadelphia, plans for the development of the new capital city of Washington were being realized. Before the United States Capitol was used by the Senate or House of Representatives, it was used as a church—or perhaps more accurately as churches. In his plans for America's new capital, Peter L'Enfant chose Jenkins Hill as the site for the Capitol building, and on September 18, 1793, President Washington laid the cornerstone for the new Capitol of Washington. But in Philadelphia where Congress under the new United States Constitution had temporarily convened, a yellow fever epidemic was raging, claiming the lives of nearly 5,000 people between August 1 and November 9. Three leaders labored vigorously to stem the tide of death in Philadelphia, one white and two black men.

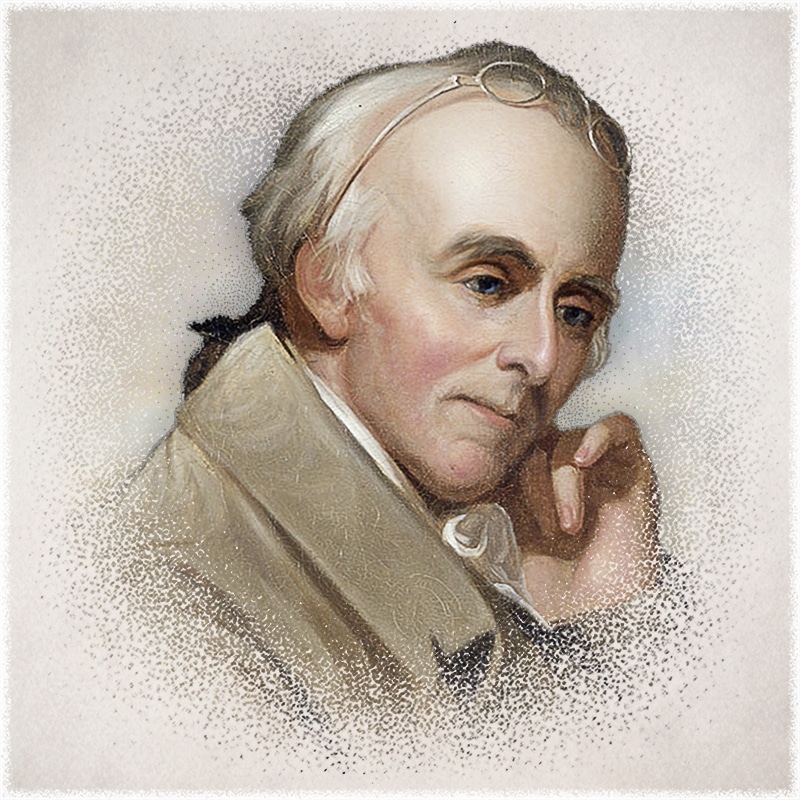

The first of the three was Founding Father, Dr. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence and Surgeon General of the American Revolutionary Army. Dr. Rush was the most well-known physician in America at the time and a deeply committed evangelical Christian. Educated at Princeton and imbued with Calvinism, Dr. Rush became a Methodist in his theology after having read John Fletcher's Checks to Antinomianism. In his autobiography, Dr. Rush noted he had been raised and educated under the Calvinistic Westminster Confession, then observed…

I then read for the first time Fletcher's controversy with the Calvinists, in favor of the universality of the atonement. This prepared my mind to admit the doctrine of universal salvation, which was then preached in our city by the Rev. Mr. Winchester. It embraced and reconciled my ancient Calvinistical and my newly adopted Arminian principles.[1]

Two other men were of great assistance in fighting the epidemic—both of whom were Christian ministers. Two black ministers and their parishioners were part of the massive effort to minister to the sick and dying of Philadelphia. Richard Allen (February 14, 1760 – March 26, 1831) was the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the first independent black denomination in the United States. Born into slavery in Delaware, Richard and two of his siblings began to attend the local Methodist Society, which welcomed both slaves and free blacks. At the age of seventeen, Richard joined the Methodists, and in 1780, purchased his freedom. In 1784, Richard was licensed as a Methodist preacher at the Christmas Conference that established American Methodists as a separate denomination under the leadership of Francis Asbury and Dr. Thomas Coke. Also present at the Christmas Conference was Harry Hosier, traveling companion of Asbury; the state of Indiana takes its nickname from Harry Hosier (see our article, Harry Hosier: Preacher Gives Indiana Its Nickname). In 1786, Richard became a preacher at St. George's Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but in time, began the African Methodist Episcopal Church, where free blacks and slaves could worship without racial oppression.

Absalom Jones (November 7, 1746 – February 13, 1818) was the second black minister who offered extensive care to the sick and dying of the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic. Like Allen, Absalom Jones was also born into slavery in Delaware. Taken to Philadelphia by his owner, Absalom married an enslaved woman of a neighbor in 1770; the ceremony was performed by the first chaplain of the Continental Congress, Episcopal minister, Rev. Jacob Duché—remembered for his first prayer at the opening of the First Continental Congress. In 1778, Absalom purchased his wife's freedom, thereby also freeing their children. In 1784, Absalom's owner manumitted him, providing for his freedom. Three years after receiving his freedom, Absalom and Richard Allen established the Free African Society in Philadelphia, a mutual aid society for African Americans of the city.

Absalom became a lay minister at the interracial congregation of St. George's Methodist Episcopal Church of Philadelphia, where Richard Allen also was a minister. But in 1792, Absalom and Richard were told they could not be seated or kneel on the first floor but had to be segregated from other members by sitting against the wall or in the gallery or balcony. After prayer, Richard, Absalom, and most of the church's black members walked out. Absalom united with the Episcopal Church to found the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the first black church in Philadelphia which opened its doors on July 17, 1794. Absalom was ordained a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

The year after they left St. George's Methodist Church, Richard and Absalom united with Dr. Rush in an effort to minister to those struck by the yellow fever epidemic. During the 1742 yellow fever epidemic in Charleston, South Carolina, Dr. John Lining had been led to believe African slaves appeared to be affected at lower rates than whites. Relying on Dr. Lining's observance, Dr. Rush assumed that blacks possessed a higher natural immunity and wrote a letter to the newspapers of Philadelphia under the pseudonym "Anthony Benezet," a Quaker who had provided schooling for blacks. In his letter, Dr. Rush suggested that blacks possessed grater immunity and solicited them to offer their services to attend the sick. Richard and Absalom immediately responded and organized nurses to assist in the effort. However, Dr. Lining's observation and Dr. Rush's reliance upon it proved false in Philadelphia, with blacks succumbing to the epidemic in proportionate numbers to whites.

On September 26th, ninety-six victims succumbed to the ravages of the plague. That number increased until October 11th, when 119 died in one day. Gravediggers worked around the clock. In fear, family members fled from each other, concerned that loved ones would communicate the fever to them. By mid-October, the mortality rate peaked when autumn's frosts began, bringing the epidemic to an end in November. Nearly one-tenth of the population of Philadelphia had succumbed to the fever. President Washington, along with his family, remained in Virginia, but there was no one to advise him.

With the onset of autumn, the plague began to recede. The frost came and began its work of killing the disease carrying mosquitoes. Though the specter of death receded with the advance of winter, its presence was still deeply felt. Those citizens who survived were so numbed by the loss of so many family and friends that it left them unable to pick up their lives.

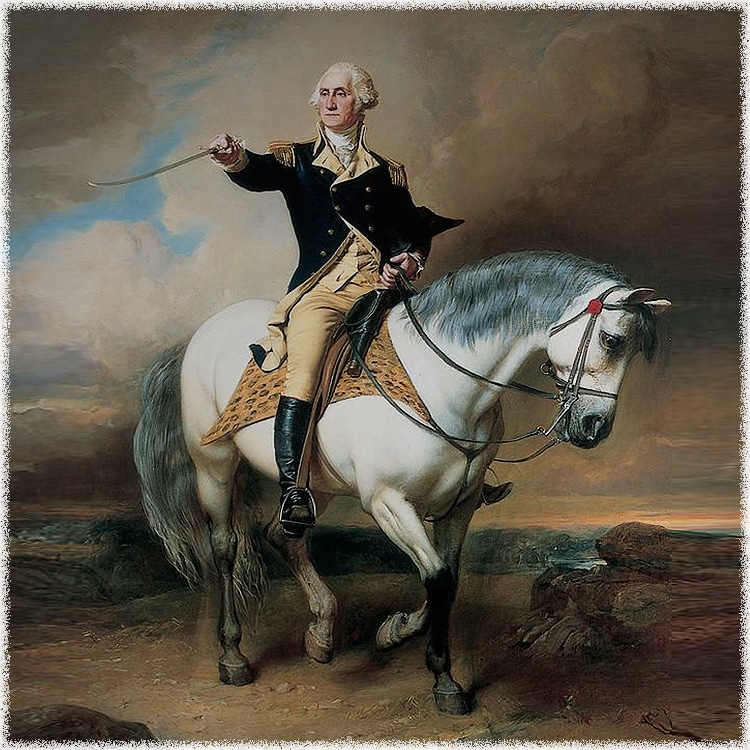

In this state, the city of Philadelphia remained until early November. On the morning of November 11th, a lone figure began to make its way into the city. From behind curtains, citizens peered through their windows at the solitary gentleman that was breaking the silence of the town. Mounted upon a great white horse, the tall man slowly made his way through the city, slightly bowing at any sign of life that peered out at him from drawn shades or cracks in doorways. But this man was no stranger to the citizens of the nation's capital. From homes, gaunt figures began to appear, window sashes thrown open as muffled voices were once again heard in the streets, as this figure breathed hope in the citizens of Philadelphia. That morning, by his very presence, George Washington gave new life to the corpse of Philadelphia, just as he had assisted in the birthing of a young nation.

More than two centuries ago, the Father of America broke the clutch of death and bondage that gripped the city of Philadelphia, simply by riding down the forsaken streets of the town that was then the nation's capital. The very presence of George Washington was sufficient to revive the spirit of the city of Philadelphia and the hope of a fledgling nation. But more than two millennia ago, Jesus Christ promised his followers that his Father attended the funeral of every sparrow and arrayed the lilies of the field in opulent apparel, and if the Father cared so much about those things that quickly perish, how much more the Father cares about those who seek His highest willingness (Matthew 6:25-34). Living in a fallen world, we take comfort and encouragement from the presence of heroes and heroines, but how much more the followers of Jesus Christ should take real comfort from the One who has promised, "I will never leave you, nor forsake you" (Hebrews 13:5).

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] It is likely John Fletcher's Checks to Antinomianism was the single greatest influence in the decline of Calvinism's theological dominance in America. See Benjamin Rush, A Memorial Containing Travels through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush, Born Dec. 24, 1745 (Old Style) Died April 19, 1813, Written by Himself; Also Extracts from His Commonplace Book as Well as a Short History of the Rush Family in Pennsylvania, Published Privately for the Benefit of His Descendants (Lanoraie, PA: Louis Alexander Biddle, 1905), 125.