Harry Hosier: Preacher Gives Indiana Its Nickname

In America, both the white and black communities have lost a sense of the influence that the Christian faith has exercised upon each respective community. Unable to recount pivotal historical details concerning the formative influence of Christianity upon America, the fraudulent claims of secularism and irreligion appear most plausible to the un- or ill-informed. Concerning the origin of the state nickname, "Hoosier," this fact is reflected by Indiana's most dedicated historians. For many years, speculation has dominated the discussion concerning the origin of this nickname, and for some, an answer is not forthcoming. The Indiana Historical Society, as reflected in the following statement, also is not prepared to answer the question of the origin of the state nickname:

How did Indiana get its nickname as "The Hoosier State"? And how did people from Indiana come to be called "Hoosiers"? There are many different theories about how the word Hoosier came to be and how it came to have such a connection with the state of Indiana.[1]

Despite the secular climate of American social life that does not readily acknowledge or welcome religious influence upon any sphere of culture, the fact is that the most plausible explanation for the origin of Indiana's nickname is the influence of a black preacher–Harry Hosier.

Article Contents

In Washington, D.C. stands a memorial dedicated by President Calvin Coolidge to the untiring efforts of Francis Asbury, Bishop of the Methodist Church in America. On August 17, 1771, John Wesley presented a special plea to his itinerant preachers at the Bristol conference in England for ministers willing to labor in America. Francis Asbury responded and almost immediately set sail for the New World, landing in Philadelphia on October 27 that same year. As a result of Asbury's tireless efforts, Methodism became the largest Protestant denomination in America during the nineteenth century. But, like many mainline denominations, much of American Methodism lost its evangelical message throughout the twentieth century and embraced the destructive influences of liberalism. As an itinerate minister, Asbury travel widely throughout young America, often showing his ministers the way by venturing into the wilderness frontier. As a result of his extensive travels, Asbury became the most widely recognized figure during that era of American history–likely more widely recognized than the Father of America, George Washington.

In his extensive travels, Bishop Asbury often was accompanied by traveling companions who were preachers themselves. One of Asbury's traveling companions was Harry Hosier, his last name being spelled in various ways, including Hoosier, Hosier, Hossier, Hersure, Hoshure, Hosure, and Hoshur.[2] To those who knew him best, he was better known as "Black Harry." Harry was born a slave near Fayetteville, North Carolina about 1750. Sold apparently to Henry Dorsey Gough, Harry came to reside outside of Baltimore, Maryland. Under the influence of the prayer of a slave[3] and the preaching of Bishop Asbury,[4] Mr. Gough became an influential Methodist. Building a chapel near his mansion of Perry Hall, Gough regularly assembled both whites and blacks for morning and evening prayers.[5]

Harry Hosier was released from slavery, converted to Christ, and became the first African local preacher of American Methodism.[6] From all indications, Bishop Asbury became acquainted with Harry Hosier in 1780. In the Journal of his travels in North Carolina, Asbury recorded the following entry for June 29, 1780:

Read several chapters in Isaiah. I have thought if I had two horses, and Harry (a colored man) to go with, and drive one, and meet the black people, and to spend about six months in Virginia and the Carolinas, it would be attended with a blessing [from the Lord].[7]

In less than a year, Bishop Asbury's desire became a reality. While traveling through Virginia, he called attention to a new innovation in his ministry and recorded it in his Journal for Sunday May 13, 1781:

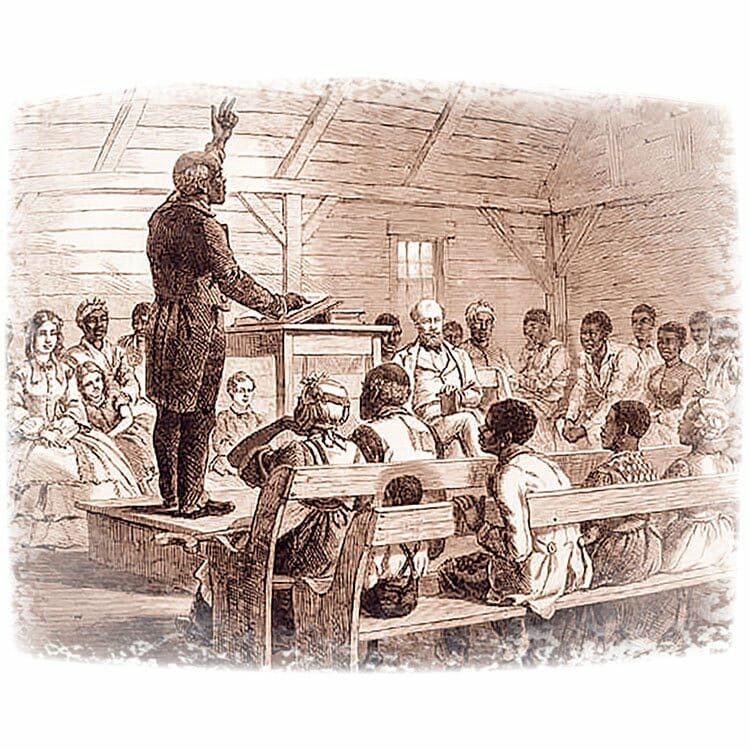

Preached at the chapel; afterward Harry, a black man, spoke on the barren fig-tree. This circumstance was new, and the white people looked on with attention.[8]

A little more than a week later, Asbury preached on "purity of heart," and Harry preached to the "Negroes," telling "them they may fall from grace, and that they must be holy."[9] For his preaching against "eternal security," Hosier was particularly disliked by Virginia Baptists, who as disciples of Calvinism preached that those who were once in grace would always remain in grace.[10]

From this small, seemingly insignificant beginning arose one of the most influential preachers of early America–Black or White. In the years that followed, Harry Hosier became one of the most distinguished American preachers. Signer of the Declaration of Independence and one of three of the most important Founding Fathers,[11] Dr. Benjamin Rush, was so impressed with Harry's ability as a preacher that he said, "making allowances for his illiteracy he was the greatest orator in America."[12] Contemporary of Asbury, Methodist Bishop, Dr. Thomas Coke, was also deeply taken by Hosier's preaching ability and exclaimed: "I really believe he is the best preacher in the world. There is an amazing power attends his preaching . . . "[13] Another of Bishop Asbury's traveling companions, Rev. Henry Boehm, noted Harry's ability, saying, "Crowds flocked to hear him, not only because he was a colored man, but because he was eloquent."[14]

How Indiana Received Its Nickname

Prior to the rise of the Second Great Awakening in the 1790s, Harry Hosier had traveled for nearly a decade within Methodist circles, accompanying some of the most well known Methodist leaders of the late-eighteenth century on evangelistic tours.[15] Though illiterate, Harry Hosier preached as far north as New England, and Asbury's Journal records the fact that Hosier also preached in the territory previously known as the Middle Colonies, and there can be little doubt, that–as traveling companion of Bishop Asbury–Hosier would have preached in his natal southern states. Thus, the influence of Harry Hosier spanned the entire nation. Along with the growing number of Methodists, Hosier's impact was very extensive, so it is only natural that his name should become associated with those who attended his preaching appointments and who held to his Methodist theology.

In 1995, Professor William D. Piersen of Fisk University (Nashville) published an article titled, "The Origin of the Word 'Hoosier': A New Interpretation," in the Indiana Magazine of History.[16] In his article, Piersen described those who had attended the camp meetings, conferences, revivals, Love Feasts, and other religious gatherings where Harry spoke over a period of nearly a quarter of a century. As a former slave, Harry found a natural home among the Methodists who preached against slavery and who often worshipped with former slaves on the American frontier. Because of this close fellowship, writes Piersen, ". . . it does not seem at all unlikely that Methodists and then other rustics of the backcountry could be called 'Hoosiers'–disciples of the illiterate black exhorter Harry Hoosier..."[17] Piersen continues:

It is likely that, as memories of the preacher "Black Harry" slipped away, and as the white people of the frontier adopted the nickname Hoosier for themselves, the term lost its original racial connotations ... and came to mean simply an illiterate, ignorant, and uncouth yahoo.[18]

Such nicknames for religious adherents are common in history. The term "Methodist" appears to have been given to John Wesley and his followers because of their methodical approach to Christian living. While some terms that have been applied to Christians of varying theological background have continued as terms describing those groups, sometimes the origin of those terms or expressions and their application are altogether lost. Such is the case for the expression "red neck." The first recorded use of the expression "red-neck" occurred in 1830 as an expression of derision for frontier Presbyterians in North Carolina.[19] Such derogatory religious expressions were used on the American frontier. However, it may be that these evangelical Methodists were proud of the expression and regarded it as a badge of honor, rather than a label of dishonor.

Harry Hosier's listeners pushed out of the Appalachian Mountains into the Mid-West, many of whom settled in present-day Indiana. The fact that Methodists were influential in the settlement of Indiana is further support of the fact that a black Methodist preacher gave Hoosiers their nickname.

Bishop Asbury's Journal records the fact that as late as spring 1803, Hosier continued to travel with him,[20] but sometime after this, this great preacher–Harry Hosier–turned away from Christ. Thankfully, he was restored to a living faith in Christ before his death in 1810. Another traveling companion of Asbury reluctantly recounted this sad era of Hosier's life and his restoration to Christ in the following lines:

'Tis painful to mar a picture so beautiful [as the life of Harry Hosier]. Gladly I will leave it as it is. But, alas! poor Harry was so petted [for his speaking ability] and made so much of that he became lifted up [with pride]. Falling under the influence of strong drink, he made shipwreck of the faith, and for years he remained in this condition. He was afterward reclaimed, and died in peace in Philadelphia in 1810, and was buried in Kensington.[21]

For the thousands who flocked to hear Harry Hosier preach, the name "Hoosier" was a memorial to both the man and his message–of freedom from human bondage and freedom from the bondage of sin! People from Indiana should take pride in having the most distinctive state nickname, but they may justly exercise greater appreciation for the person whose name it was.[22]

Appendix: Boehm Remembers "Black Harry"

Reverend Henry Boehm was one of Bishop Asbury's traveling companions and one of the executors of Asbury's will. Prior to Boehm accompanying the Bishop, Asbury had other traveling companions who accompanied him, among whom was Harry Hosier or "Black Harry." On May 2, 1803, the Philadelphia Conference of the Methodist Church was convened at Duck Creek Cross Roads. It was here that Henry Boehm first met and heard Hosier preach. The Conference lasted for four days with sessions in which sermons were delivered by various ministers and were preceded by "powerful" prayer meetings. Boehm, deeply impressed with Harry Hosier, provides the following recollection in his journal and is presented here in an attempt to relate the influence of Hosier from an eye-witness of his ministry:

I heard, during the session, a number of admirable sermons: one from Richard Sneath, on Matt. vi, 10, "Thy kingdom come ;" another by Thomas Foster, from Isaiah xlv, 18, a profitable and pointed discourse; the power of God rested on the congregation. I also heard "Black Harry," who traveled with Bishop Asbury and Freeborn Garrettson. He was a perfect character; could neither read nor write, and yet was very eloquent. His text was, "Man goeth to his long home;" his sermon was one of great eloquence and power. The preachers listened to this son of Ham with great wonder, attention, and profit. I shall say something more concerning him.

. . .

Having heard this African preach, I have been asked a great many questions concerning him. The preaching of a colored man was, in those days, a novelty. Harry traveled with Bishop Asbury as early as 1782;[23] also with Dr. Coke, Bishop Whatcoat, and Freeborn Garrettson. Crowds flocked to hear him, not only because he was a colored man, but because he was eloquent. Mr. Asbury wished him to travel with him for the benefit of the colored people.

Some inquire whether he was really black, or whether Anglo-Saxon blood was not mixed in his veins? Harry was very black, an African of the Africans. He was so illiterate he could not read a word. He would repeat the hymn as if reading it, and quote his text with great accuracy. His voice was musical, and his tongue as the pen of a ready writer. He was unboundedly popular, and many would rather hear him than the bishops. In 1790, he traveled with Mr. Garrettson through New England and a part of New York. In Hudson, Mr. Garrettson says: "I found the people curious to hear Harry. I therefore declined, that their curiosity might be satisfied. The different denominations heard him with much admiration, and the Quakers thought, as be was unlearned, he must speak by immediate inspiration." Another time he says: "Harry exhorted after me to the admiration of the people." Again, near Gen. Van Courtland's, he says: "The people of this circuit are amazingly fond of hearing Harry." In Canaan, Conn., Mr. Garrettson preached, and says: "Harry preached after me with much applause." The same afternoon Mr. Garrettson preached in Salisbury, and adds: "I have never seen so tender a meeting in this town before, for a general weeping ran through the congregation, especially when Harry gave an exhortation."

Dr. [Benjamin] Rush heard him and admired his eloquence. Dr. Coke heard him preach, soon after his arrival in America, on the Peninsula, and said, "I am well pleased with Harry's preaching."

'Tis painful to mar a picture so beautiful. Gladly I will leave it as it is. But, alas! poor Harry was so petted [for his speaking ability] and made so much of that he became lifted up [with pride]. Falling under the influence of strong drink, he made shipwreck of the faith, and for years he remained in this condition. He was afterward reclaimed, and died in peace in Philadelphia in 1810, and was buried in Kensington.[24]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

Selected Works

"What Is a Hoosier?" Indiana Historical Society. Last modified Accessed February 15, 2016. http://www.indianahistory.org/teachers-students/hoosier-facts-fun/fun-facts/what-is-a-hoosier#.VsJyuRhS-B8.

Asbury, Francis. Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury: In Three Volumes. 3 vols., edited by Elmer T. Clark, J. Manning Potts, and Jacob S. Payton. Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon Press, 1958.

Boehm, Henry. The Patriarch of One Hundred Years Being Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, of Rev. Henry Boehm. 1982 reprint ed. New York: Nelson & Phillips, 1875.

Licorish, Joshua E., The Encyclopedia of World Methodism. 2 vols.Nashville: United Methodist Pub. House, 1974.

Piersen, William D. "The Origin of the Word 'Hoosier': A New Interpretation." Indiana Magazine of History 91, no. 2 (1995): 189-96.

Sanderson, John. Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia: R. W. Pomeroy, 1823.

Simpson, Matthew, Cyclopedia of Methodism. Revised ed. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1880.

Stevens, Abel. History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America. 4 vols. New York: Carlton & Porter, 1864.

Webb, Stephen H. "Introducing Black Harry Hoosier: The History Behind Indiana's Namesake." Indiana University. Last modified Accessed February 29, 2016. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/11895/17497.

[1] "What Is a Hoosier?," Indiana Historical Society, accessed February 15, 2016. http://www.indianahistory.org/teachers-students/hoosier-facts-fun/fun-facts/what-is-a-hoosier#.VsJyuRhS-B8.

[2] William D. Piersen, "The Origin of the Word 'Hoosier': A New Interpretation," Indiana Magazine of History 91, no. 2 (1995): 192.

[3] Piersen, "Origin of the Word 'Hoosier'," 192.

[4] Cyclopedia of Methodism, Revised ed., s.v. "Gough, Henry Dorsey."

[5] Cyclopedia of Methodism, s.v. "Gough, Henry Dorsey."

[6] Nolan B. Harmon, The Encyclopedia of World Methodism, s.v. "Hosier, Harry."

[7] Francis Asbury, Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury: In Three Volumes, 3 vols. (Nashville, Tenn.: Abingdon Press, 1958), 1:362.

[8] Asbury, Journal and Letters, 1:403.

[9] Asbury, Journal and Letters, 1:403.

[10] Piersen, "Origin of the Word 'Hoosier'."

[11] John Sanderson, Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence (Philadelphia: R. W. Pomeroy, 1823), 4:285.

[12] Abel Stevens, History of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America, 4 vols. (New York: Carlton & Porter, 1864), 1:174.

[13] Harmon, The Encyclopedia of World Methodism, s.v. "Hosier, Harry."

[14] Henry Boehm, The Patriarch of One Hundred Years Being Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, of Rev. Henry Boehm, 1982 reprint ed. (New York: Nelson & Phillips, 1875), 91.

[15] In addition to Asbury, Hosier also accompanied Thomas Coke, Freeborn Garrettson, Richard Whatcoat, Henry Boehm, and others. Harmon, The Encyclopedia of World Methodism, s.v. "Hosier, Harry."

[16] Volume 91, no. 2 (1995): 189-96.

[17] Piersen, "Origin of the Word 'Hoosier'," 193.

[18] Piersen, "Origin of the Word 'Hoosier'," 195.

[19] Piersen, "Origin of the Word 'Hoosier'," 193, 195.

[20] Asbury, Journal and Letters, 2:389. It appears this was the first time that another of Asbury's traveling companions, Henry Boehm, met Harry Hosier. See Boehm, Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, 88-92.

[21] Boehm, Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, 89-92.

[22] Stephen H. Webb, "Introducing Black Harry Hoosier: The History Behind Indiana's Namesake," Indiana University, accessed February 29, 2016. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/11895/17497.

[23] To be more exact, it was May of 1781. See, Asbury, Journal and Letters, 1:403.

[24] Boehm, Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, 89-92.

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Harry Hosier

Podcast: 'Harry Hosier: Preacher Gives Indiana Its Nickname,' by Dr. Stephen Flick.