Thomas Paine Argues, “No King But God”

A growing number in America have suggested that religion or Christianity should have no place in the political life of the nation. The Founding Fathers, however, never believed nor advocated irreligion. In fact, secularists cannot demonstrate a single occasion in any of the original Thirteen Colonies and subsequent Thirteen United States that irreligion or deism had any impact upon the political life of those individual states or the nation as a whole. The overwhelming majority of Founding Fathers were members of orthodox Christian denominations, and they took their faith with them into the political arenas of their states and fledgling nation. Thomas Paine

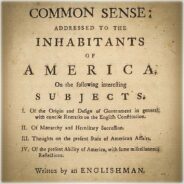

One of the individuals advocates of irreligion promote to push Christianity from the politics and the public arena in general is Thomas Paine, author of the widely acclaimed book, Common Sense. When Common Sense first appeared on January 10, 1776, it was an immediate success. One of the three most important Founding Fathers, Dr. Benjamin Rush, is reported to have reflected upon the publication of Paine's book, saying, "That book burst forth from the press with an effect that has been rarely produced by types and paper, in any age or country."[1] That Paine was not irreligious or anti-Christian at this point in his life is evident by the relationships he sustained with deeply committed evangelical Christians such as Dr. Rush. In fact, as one of Paine's biographers noted, "It was he [Dr. Benjamin Rush]who encouraged Thomas Paine to write Common Sense, for which Rush not only supplied the title but many of its ideas."[2] The influence of Common Sense was also noted by one of Paine's most bitter enemies: "The cannon of Washington was not more formidable to the British than the pen of the author of Common Sense."[3]Thomas Paine

Anti-Christian and irreligious forces will find no support in the Thomas Paine who wrote Common Sense for their suppression of religion in public life. In fact, Thomas Paine insists that human government must be based upon God's government.

Article Contents

When American colonists revolted against King George III for his denial of their rights as Englishmen and divinely created human beings, they appealed to the authority of a Higher Monarch—God. One of the reported mottos of the Revolution is reported to have been, "No king, but King Jesus." Historians and unbelievers seeking to deny the religious influence and origin of America have rejected this claim. In his brief online article, J. L. Bell summarized the arguments against the use of the motto, noting that historical details used by Christians to support the claims for the motto were inaccurate. Calling attention to the article "Fake History" that identified these historical discrepancies, he wrote:

• Samuel Adams had been in Lexington earlier that morning, not John.

• Jonas Clarke was town minister and thus by law not a “militia leader.”

• Clarke wasn’t on the common during the confrontation with the British.

• Most important, there’s no evidence for this exchange.

We have dozens of first-hand descriptions of the confrontation on Lexington common from 1775 and afterwards, coming from men on both sides of the conflict. Not one includes the words “No king but Jesus.”[4]

A survey of online articles will reveal those rejecting the "No king, but Jesus" motto point to the anachronisms or false historical data as proof that this or comparable expressions were not used by the American colonists. While secularists may call attention to the lack of the use of this particular expression ("No king, but King Jesus"), they cannot point to evidence that the Founding Fathers believed that they were not under the government of God. If they are correct, then it is one more stone removed from the foundation supporting the belief that America was founded upon Christianity—but they are not correct!

What many now fail to realize is that the Thomas Paine of the 1770s and 1780s (or the era of the American Revolution) was not the later Thomas Paine of the 1790s and early nineteenth century. Characteristic of much of his life, Paine soon found himself at odds with leading figures of the American Revolution. Following the War of Independence, he returned to England, where he was born. A few years later, he ventured to France (1790) where he was caught-up in the events of the French Revolution. Unlike the American Revolution, the French Revolution of 1789 and the many years that followed were the result of the godless influence of Voltaire, Rousseau, and the European "Intellectuals." From these wells of irreligion that sprang from the French Revolution, Paine drank freely and deeply—a fact that was reflected in his subsequent writings.

Though Paine produced other works, two writings defended the anti-Christian French Revolution and the philosophy that justified its horrors. The first of these two works, Rights of Man (1791), included thirty-one articles that argued in defense of revolution when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people.[5] The second work, The Age of Reason—published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807, was a traditional deistic attack upon Christianity, institutional religion, and denied the legitimacy of the Bible. Particularly the latter work amounted to a betrayal of the Founding Father's understanding of the foundation of human government.

It is not possible to argue that the latter Thomas Paine was the "real" influence upon the origin of America. No; it was the younger, Thomas Paine who exerted a religious influence upon the formation of America that was consistent with the Christian convictions of other Founding Fathers. Paine's Common Sense made no attempt to disparage or ridicule the Bible, but rather, employed Scripture and Christian thought to develop his arguments in favor of American independence. While a detailed analysis of this book would further support this claim, only a couple of extended quotes should be sufficient to convince the most candid readers.

First, the fact that the Bible is used favorably by Paine as part of his collage detailing his understanding of human government which began with the "Sovereign, the King of heaven":

The children of Israel being oppressed by the Midianites, Gideon marched against them with a small army, and victory, thro' the divine interposition [providence], decided in his favor. The Jews elate with success, and attributing it to the generalship of Gideon, proposed making him a king, saying, Rule thou over us, thou and thy son and thy son's son. Here was temptation in its fullest extent; not a kingdom only, but a hereditary one, but Gideon in the piety of his soul replied, I will not rule over you, neither shall my son rule over you. The Lord shall rule over you. Words need not be more explicit; Gideon doth not decline the honor, but denieth their right to give it; neither doth he compliment them with invented declarations of his thanks, but in the positive stile of a prophet charges them with disaffection to their proper Sovereign, the King of heaven.[6]

Second, Paine extended his argument in favor of the rule of the "Sovereign, the King of heaven" to include his right to rule in America. Writing eleven years prior to the drafting of the United States Constitution, Paine referred to a written form of government he called a "Charter." What is critical to Paine's understanding of human government is the fact that he believed the supreme law giver was the One who "reigns above," and He has made his law known through "the Divine Law, the Word of God."

But where, say some, is the King of America? I’ll tell you, friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Great Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the Charter; let it be brought forth placed on the Divine Law, the Word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other. But lest any ill use should afterwards arise, let the Crown at the conclusion of the ceremony be demolished, and scattered among the people whose right it is.[7]

For Thomas Paine, there was "No king, but God!" He believed that human government must proceed from divine government, or "the Charter" (or Constitution) must be founded upon or arise out of, or be "placed on the Divine Law, the Word of God."

Thomas Paine did have a great impact upon the origin of America as an independent nation, but it was the religious, not irreligious Thomas Paine that exercised this influence. And, given the fact that Americans were Trinitarians (believing in God the Father, Son, and Spirit), they believed Jesus was God, and, therefore, there was little or no difference between the expressions, "No king, but Jesus" and "No king, but God."

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

[1] Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Co., 1923), 7.

[2] Alyn Brodsky, Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician, 1st ed. (New York: Truman Talley Books, 2004), 5.

[3] Paine, Common Sense, 8.

[4] J. L. Bell, "The “No King but Jesus” Myth," January 10, 2017; http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2014/04/the-no-king-but-jesus-myth.html.

[5] "Rights of Man," Wikipedia, January 27, 2016; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rights_of_Man.

[6] Paine, Common Sense, 25-26.

[7] Paine, Common Sense, 57.