The First Prayer in Congress

All four of America's organic laws were composed by the Continental[1] and Confederation[2] Congresses, which preceded the United States Congress under the Constitution. An organic law is a law that cannot be subverted or overruled by any other law. America's four organic laws are the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), the Articles of Confederation (November 15, 1777), the Northwest Ordinance (July 13, 1787), and the Constitution (September 17, 1787)First Prayer in Congress.

What is important to realize is that the Continental and Confederation Congresses composed these four organic laws—the most authoritative laws in America, and these laws remain binding on America. At the same time as the Continental and Confederation Conferences were constructing these laws, they also were observing Christian practices such as fasting, praying, and giving thanks to God. In fact, Congress—from 1775 to 1784—composed sixteen spiritual proclamation, asking each of the states to publicize Congresses fast, prayer, and thanksgiving proclamations. By their examples, the Congresses that gave America its most authoritative laws demonstrated that they believed Christian practices should be observed. Representatives to Congress were not ashamed of their faith. In fact, the first prayer in Congress demonstrates that delegates to Congress began to observe Christian practices at the beginning of the First Continental Congress.First Prayer in Congress

Article Contents

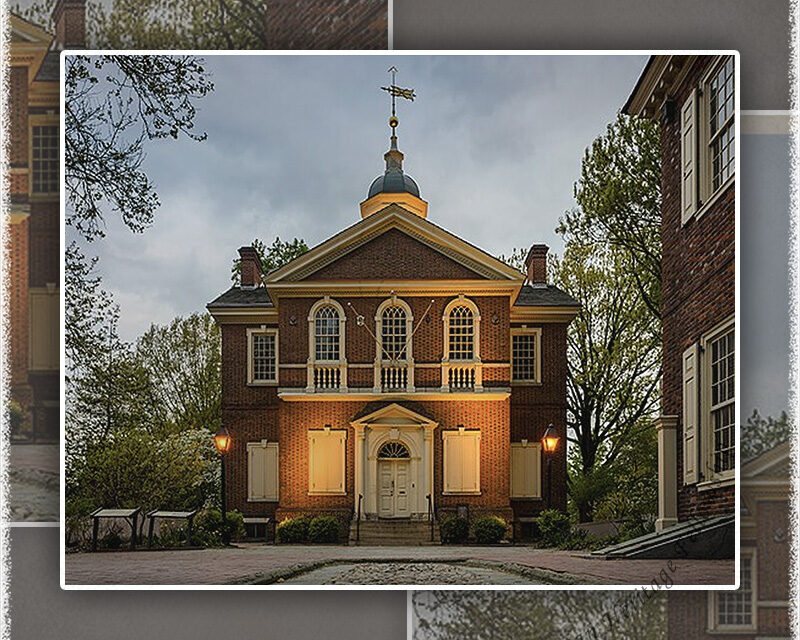

On Monday, September 5, 1774, the First Continental Congress was convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At ten o'clock in the morning, fifty-three delegates from twelve colonies met at the City Tavern and proceeded from there only a short distance to Carpenter's Hall where they began their work.[3] The only colony not represented was Georgia. Peyton Randolph, a delegate from Virginia, was unanimously elected Chairman or President of Congress and served most of two months of the First Continental Congress, but fell ill and was replaced on October 22 by Henry Middleton. During his brief presidency of Congress (September 5—October 22, 1774), Peyton Randolph presided over the initial Christian influences that would characterize America's earliest form of federal government.

Following the election of Randolph as President, Congress then proceeded to elect Charles Thomson, a delegate from Pennsylvania, as its secretary. While Congress had sixteen presidents from 1774-1789 (some serving more than one term), it only had one secretary—Charles Thomson, a Bible scholar. After nineteen years of work, Thomson published a four-volume English translation of the Greek Old (Septuagint) and New Testaments (1808).[4] Seven years later he published A Synopsis of the Four Evangelists (1815).[5]

Congress Votes to Begin with Prayer

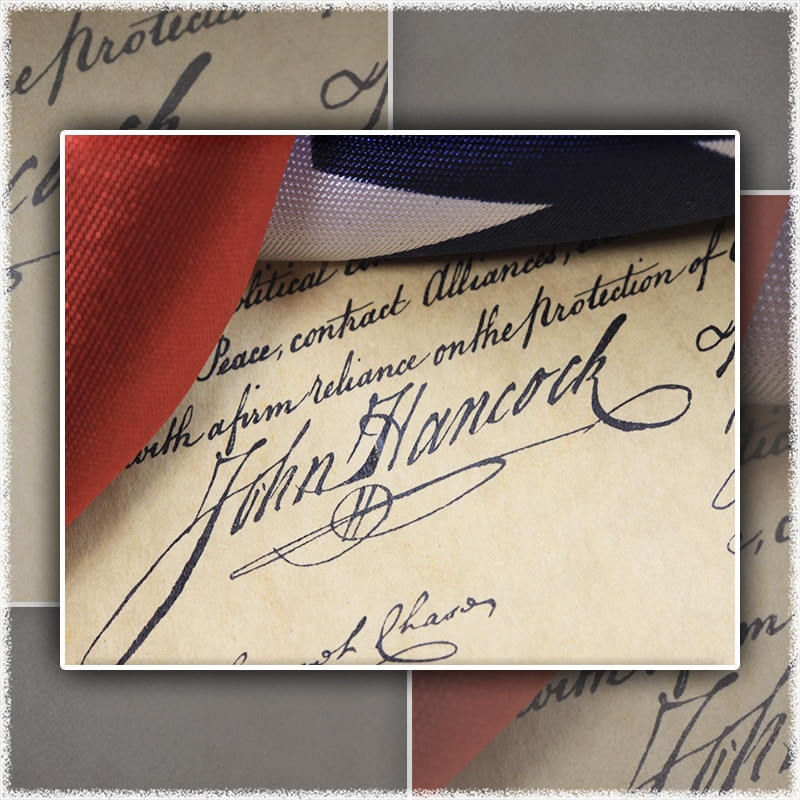

On the second day of Congress (September 6), a request was placed before the delegates to begin the deliberation of Congress the following day with prayer. Though some uncertainty remains concerning who was responsible for the motion to begin Congress with prayer, private correspondence and the Journals of Congress appear to suggest that Thomas Cushing of Massachusetts first proposed that their deliberations open with prayer but met with resistance from John Jay and Edward or John Rutledge "on the ground of a diversity in religious sentiments" of the members of Congress.[6] Ironically, none of those objecting to the proposal were irreligious. In fact, John Jay was appointed by President Washington as the First Chief Justice under the Constitution and was the second president of the American Bible Society, following Elias Boudinot, who was also a member of Congress and tenth President of Congress. To resolve the issue of denominational differences, the Congregationalist, "Samuel Adams [the 'Father of the American Revolution']asserted he was no bigot, and could hear a prayer from any gentleman of piety and virtue, who was at the same time a friend to his country; and nominated Duche. . . "[7]

Rev. Jacob Duche was the Anglican pastor of Christ Church in Philadelphia; because of its influential role during the American Revolution, Christ Church was also known as "the Nation's Church."[8] A simple entry in the Journals of Congress for September 6, 1774 records the beginning of Congress' observances of Christian practices:

Resolved, That the Revd. Mr. Duche. . . be desired to open the Congress tomorrow morning with prayers, at the Carpenter's Hall, at 9 o'clock.[9]

Among the thousands of pieces of historical evidence that demonstrate America's Founding Fathers had no intention of pushing Christianity out of the public arena, this vote in the First Continental Congress taken on September 6, 1774 stands foremost. Because the Continental and Confederation Congresses mark the beginning of America's federal government, Congress' own example demonstrates that the Founding Fathers fully intended to practice their Christian faith in official state ceremonies, and what they claimed for themselves they never intended to deny to fellow citizens.

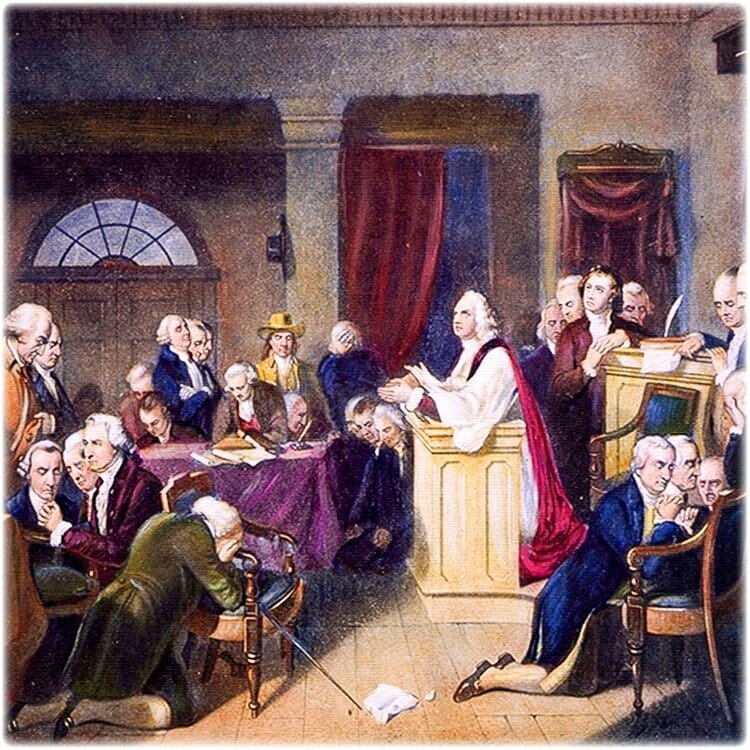

Complying with the request of Congress, Rev. Duche. . . attended in full clerical attire, leading Congress in the devotional exercise for that day listed in his Anglican Book of Common Prayer from Psalm 35. Then Rev. Duche offered an extemporaneous prayer, saying,

O Lord our Heavenly Father, high and mighty King of kings, and Lord of lords, who dost from thy throne behold all the dwellers on earth and reignest with power supreme and uncontrolled over all the Kingdoms, Empires and Governments; look down in mercy, we beseech Thee, on these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod of the oppressor and thrown themselves on Thy gracious protection, desiring to be henceforth dependent only on Thee. To Thee have they appealed for the righteousness of their cause; to Thee do they now look up for that countenance and support, which Thou alone canst give. Take them, therefore, Heavenly Father, under Thy nurturing care; give them wisdom in Council and valor in the field; defeat the malicious designs of our cruel adversaries; convince them of the unrighteousness of their Cause and if they persist in their sanguinary purposes, of own unerring justice, sounding in their hearts, constrain them to drop the weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle!

Be Thou present, O God of wisdom, and direct the councils of this honorable assembly; enable them to settle things on the best and surest foundation. That the scene of blood may be speedily closed; that order, harmony and peace may be effectually restored, and truth and justice, religion and piety, prevail and flourish amongst the people. Preserve the health of their bodies and vigor of their minds; shower down on them and the millions they here represent, such temporal blessings as Thou seest expedient for them in this world and crown them with everlasting glory in the world to come. All this we ask in the name and through the merits of Jesus Christ, Thy Son and our Savior.[10]

Rev. Duche's reading of Scripture and prayer wielded considerable influence over the members of Congress.[11] So deeply moved by this experience was John Adams that he dedicated much of that day's journal entry to recount the opening of Congress that morning:

Wednesday. Went to Congress again, heard Mr. Duche. . . read prayers; the collect for the day, the 7th of the month, was most admirably adapted, though this was accidental, or rather providential. A prayer which he gave us of his own composition was as pertinent, as affectionate, as sublime, as devout, as I ever heard offered up to Heaven. He filled every bosom present.[12]

Prayer Characterizes Life of Congress

That America's Founding Fathers were overwhelmingly not deists or irreligious is evident from the fact that one of the first decisions of the First Continental Congress was to seek God's will in prayer and involve a Christian chaplain in the political life of Congress.

As the First Continental Congress neared an end, delegates made provision for another Congress to "be held on the tenth day of May next" if the grievances they identified were not addressed by the British Parliament.[13] Far from wishing to sever ties with their British homeland, Congress held out hope that God would intervene to affect the peace of the entire British empire. This desire was expressed in a letter of intent sent by Congress to St. Johns parish in Georgia—because Georgia did not send a delegate to the First Continental Congress. In their letter, the members of Congress solicited Georgia's involvement for the American cause:

Gentlemen,

The present critical and truly alarming state of American affairs, having been considered in a general Congress of deputies, from the colonies of New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode-island, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the lower counties on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, and South-Carolina, with that attention and mature deliberation, which the important nature of the case demands, they have determined, for themselves and the colonies they represent, on the measures contained in the enclosed papers; which measures they recommend to your colony to be adopted with all the earnestness, that a well directed zeal for American liberty can prompt. So rapidly violent and unjust has been the late conduct of the British Administration against the colonies, that either a base and slavish submission, under the loss of their ancient, just, and constitutional liberty, must quickly take place, or an adequate Opposition be formed.

We pray God to take you under his protection, and to preserve the freedom and happiness of the whole British empire. We are as [...]

[By order of the Congress,

Henry Middleton, President.][14]

The members of Congress did not believe that God was removed from human affairs, as the deists believed. Rather, they affirmed God's participation in the world he created by appealing to God in prayer for "his protection, and to preserve the freedom and happiness of the whole British empire." All who say that America's Founding Fathers were "deists" confess their ignorance of primary historical legal documents and are more concerned about irreligious indoctrination than they are with historical education.

While eight of the thirteen original American colonies had established state churches, all thirteen colonies contained Christian affirmations and expectations for holding public office in their charters as well as their subsequent state constitutions.[15] From the opening of the First Continental Congress, its members—who were the first to initiate America's federal government—did not exclude their Christian faith from their proceedings, but accorded it a place of honor by beginning its deliberations with prayer. A study of the fasting, prayer, and thanksgiving proclamations issued by Congress during the formation of America's federal government reveals that the Founding Fathers affirmed and employed both the principles and practices of Christianity in the affairs of the state. And, they expected that succeeding generations of Americans should enjoy the same privileges they fought and died to practice.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, term, or other important component that is featured in this article and which acts as a reference point for use in other articles throughout our site.

No index entries found.

[1] First Continental Congress (1774) and Second Continental Congress (1775-1781).

[2] The Confederation Congress began March 1, 1781 and concluded March 4, 1789, just prior the Congress under the Constitution began.

[3]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 1:13-14.

In his journals, John Adams recorded this momentous occasion in the following words: " Monday. At ten the delegates all met at the City Tavern, and walked to the Carpenters’ Hall, where they took a view of the room, and of the chamber where is an excellent library; there is also a long entry where gentlemen may walk, and a convenient chamber opposite to the library. The general cry was, that this was a good room, and the question was put, whether we were satisfied with this room? and it passed in the affirmative. A very few were for the negative, and they were chiefly from Pennsylvania and New York. Then Mr. Lynch arose, and said there was a gentleman present who had presided with great dignity over a very respectable society, greatly to the advantage of America, and he therefore proposed that the Honorable Peyton Randolph, Esquire, one of the delegates from Virginia, and the late Speaker of their House of Burgesses, should be appointed Chairman, and he doubted not it would be unanimous.

The question was put, and he was unanimously chosen.

Mr. Randolph then took the chair, and the commissions of the delegates were all produced and read.

Then Mr. Lynch proposed that Mr. Charles Thomson, a gentleman of family, fortune, and character in this city, should be appointed Secretary, which was accordingly done without opposition, though Mr. Duane and Mr. Jay discovered at first an inclination to seek further." John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, with a Life of the Author by His Grandson, Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850).

[4] The title of this work was, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Covenant, Commonly Called the Old and New Testament.

[5]Dictionary of American biography. Pub. under the auspices of American Council of Learned Societies, s.v. "Thomson, Charles."

[6] While some appear to regard Samuel Adams as attempting to lay claim to the effort to begin Congress with prayer, his letter to Joseph Warren (September 9, 1774) appears to suggest he was laying claim to a mediating role that was indifferent as to which denominational minister led in prayer. See Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:26.

[7]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:26.

[8] Catherine Millard, The Rewriting of America's History (Camp Hill, PA: Horizon House Publishers, 1991), 259.

[9]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:26.

[10] "First Prayer of the Continental Congress, 1774," Office of the Chaplain United States House of Representatives (http://chaplain.house.gov/archive/continental.html, August 21, 2015).

[11]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:27.

[12] Adams, Works of John Adams, 2:368.

[13]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:102.

[14]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:103.

[15] Virginia – Anglicanism (1606-1830, 224 year); New York – Anglicanism (1614-1846, 225 years); Massachusetts – Congregationalism (1629-1833, 204 years); Maryland – Anglicanism (1632-1867, 235 years); Delaware – No official church (1637-1792, 155 years); Connecticut – Congregationalism (1639-1818, 179 years); New Hampshire – Congregationalism (1639-1877, 238 years); Rhode Island – No official church (1643-1842, 199 years); Georgia – No official church (1663-1798, 135 years); North Carolina – Anglicanism (1663-1875, 212 years); South Carolina – Anglicanism (1663-1868, 205 years); Pennsylvania – No official church (1681-1790, 109 years); New Jersey – No official church (1702-1844, 142 years. See "Religion in the Original 13 Colonies," ProCon.org, accessed March 13, 2016. http://undergod.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=69.