America’s Founding Fathers and Camp Meeting

Early in the twenty-first-century, Islam has distinguished itself as the fastest growing religion in America.[1] As it has done throughout its history, Islam has wedded religion with permission to gratify the basest human passions of the human heart. Armed with the erroneous belief that death in battle is the surest means of securing eternal sensual pleasure, Muslims race into battle and eagerly perform the most life-threatening acts. Such heroic efforts appeal to the naive and uninformed, and for this reason, their numbers are quickly multiplying in America and around the world. To their advantage, Muslims are seizing every opportunity available to them to advance a religion of blood. To the discredit of Christian leaders, Christian institutions and agencies throughout America and various parts of the world are being allowed to languish and wither on the vine of opportunity. But America did not become the greatest nation in world history under the influence of weak leaders, but strong Christian leaders who—like contemporary and historic Muslims—seized every opportunity to advance the cause of Christ.

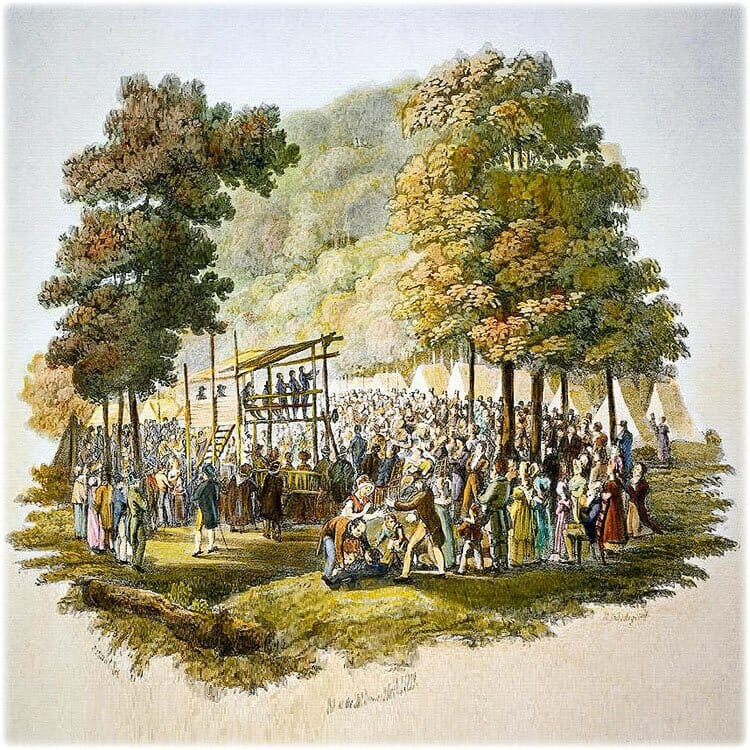

Many of the influences that the Christian faith has exercised over America have been forgotten by the nation as the twentieth century waned and the twenty-first century has begun. Arising out of a deep desire to advocate the Christian faith, many denominations initiated camp meetings in the nineteenth century that convened during the summer. These were places where the truth of the Gospel that was preached in the local church was trumpeted to hundreds of thousands of camp-meeting-going believers and unbelievers alike. Through the camp meeting, biblical truth reverberated throughout America, often with a greater influence upon believers than what was immediately realized by the pastor of the local church. America's Founding Fathers could be seen attending some of the earliest camp meeting efforts in the nineteenth century.

Governor Pierre Van Cortland was the first lieutenant governor of New York and was a deeply dedicated Methodist. His son, Philip, had been a brigadier-general during the Revolutionary War who had distinguished himself particularly at Yorktown, the crowning battle of the Revolution. Philip, eager to advance the Christian faith, attended the Methodist meetings, and if one of the Methodist circuit riders failed to appear for his appointment at the camp meetings, Philip would read a chapter from his own Bible. Of his interest and relationship to Methodist camp meetings, a companion of Bishop Francis Asbury wrote:

"Great camp-meetings were held upon his land, and multitudes were converted there."[2]

Camp meetings were influential in various denominations, but they were most commonly used by churches descending from the Methodist tradition. Under the spiritual influences of the camp meeting tradition, many political figures were shaped and molded for local, state, and federal service. The camp meeting was one important instrument in making America a spiritual and national giant in the world.

Article Contents

Between 1688 and 1710, communion practices among the Presbyterians in Scotland were closely associated with evangelical interests. Services were often used for the sake of a clear and powerful presentation of the gospel followed by the observance of the Lord's Supper. Such services were harbingers of the revival efforts that would occur on the American frontier and were often accompanied with strong emotional appeals. These communion services were forerunners of the American camp meetings and would be transported to early eighteenth-century America. The kinship that they sustain to the American camp meeting may easily be discerned from Leigh Schmidt's description of their observance in Scotland:

This long history of sacramental revivals bespoke the power of communion season to renew Presbyterian communities, to invigorate flagging saints, and to transform flagrant sinners. Over the years the sacramental occasion had come to embody an evangelical synthesis of conversionist preaching and Eucharistic practice. In the sacramental occasion the salvation of sinners was coupled with the confirmation of saints as complementary processes in the revivification of a community. The "travailing of the new birth" joined with "the work of confirmation" at these communions. These sacramental revivals were never aimed simply at the unconverted; they were for the whole community, churches and unchurched, sinners and saved. The new birth was the point of entry into a long journey heavenward upon which the pilgrim was in need of repeated renewal, reconfirmation, and perhaps even reconversion. The communion season drew people into the pilgrimage and kept them going once on the journey. For these evangelical Presbyterians salvation and the sacrament were intimately related, even inseparable. Conversion and communion had flowed together in this tradition.[4]

Scottish-American Sacramentalism (1740s)

By the 1740s, the Scottish sacramental services had been transported to the new environs of colonial America. Francis Mackemie was a founding figure of Scottish Presbyterianism in the colonies. By 1706, he and a handful of other ministers established a presbytery, but they found it to be a constant struggle to solidify the presbytery and minister to such a widely dispersed people. By the 1720s, however, Presbyterian churches had been established among the Scottish and Ulster Scottish communities.

With the transplanting of Scottish Presbyterianism to America came the practice of the revivalistic communion services. These services preceded the American camp meeting by more than half a century, but each movement shared the same fervor for the proclamation of the gospel. The evangelical spirit that imbued the life of the Scottish sacramental seasons enjoyed fellowship with the spirit that would give rise to the First Great Awakening. William Tennent, Jr., who was an important component in the rise and progress of the First Great Awakening was also a participant in the Presbyterian observance of the Lord's Supper:

In the middle colonies, where Presbyterian immigration was much heavier than in New England, sacramental occasions ere proportionally larger and more pronounced. The communion seasons-prevalent, powerful, and well attended-figured prominently in the religious life of the Presbyterian immigrants through the region. In 1744, when the evangelist William Tennent, Jr., visited "a new erected Congregation in the Towns of Maidenhead and Hopewell" in New Jersey, one of his first aims was to celebrate the Lord's Supper. The congregation, being without a settled pastor, happily embraced this opportunity. "The sacramental season," Tennent rejoiced, "was blessed to the refreshing of the Lord's dear people there, as well as to others of them which came from other Places. So that some who had been much distressed with doubts about their state, received soul-satisfying sealings of God's everlasting love: Others were supported and quickened, so that they returned home rejoicing and glorifying God." The communion season, though far removed from Ulster or Scotland, invigorated this newly gathered congregation in this distant patch of New Jersey.[5]

By the early eighteenth century, spiritual zeal in America was beginning to wane, but before mid-century, the fledgling nation experienced a spiritual revival which helped to solidify its spiritual character. The Great Awakening began in the 1730s and continued to the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Frelinghuysen Arrives in America (1720)

Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen (ca. 1691-1747), a Dutch Reformed minister, arrived in New York in 1720 and quickly settled in the Raritan Valley of New Jersey. Like German Reformed minister, Philip William Otterbein of the United Brethren in Christ, Frelinghuysen had deep pietistic sentiments. His high moral standards brought him into conflict with both his ministerial colleagues and his parishioners whom he forbade to participate in the Eucharist if they made no profession of faith ("sinner"). Through his zealous efforts, Frelinghuysen was instrumental in igniting the flames of the Great Awakening in the Middle Colonies.

Frelinghuysen Influences the Tennents (1726, ca.)

Perhaps as early as 1726[6] the revival that had started under Frelinghuysen and the Dutch Reformed Church had moved into Presbyterian circles. Thanks to the influence of Frelinghuysen, two Presbyterian ministers, William (1673-1746, the father) and Gilbert Tennent (1703-1764, the son), became the catalyst for revival among the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians in New Jersey. Gilbert Tennent, while pastoring in New Brunswick, New Jersey, met Frelinghuysen whose pietistic and evangelical zeal became a model for the young minister.

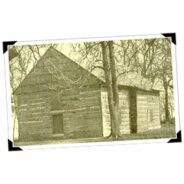

"Log College" Established (1735, ca.)

William Tennent, father of Gilbert, had tutored his four sons in theological matters in the early 1720s, and by the 1730s had provided a more formal course of education for those entering the Presbyterian ministry at his Log College in Neshaminy, Pennsylvania.[7] The Log College helped to fuel the Great Awakening by providing theological education to those who were sympathetic to the revival effort which was increasingly associated with Frelinghuysen and the Tennents. In 1738, the Presbyterian Synod attacked Tennent by voting to require all ministerial candidates to hold a degree from a New England College or European university. The escalating tension between pro- and anti-revival forces within Presbyterianism reached a climax in 1741 when the church split along Old Side and New Side party lines.[8] The New Side revival party continued to train their ministers at the Log College until the early 1740s when it ceased to exist due to Tennent's increasing age and frailty. While there is no formal institutional continuity, the Log College provided the spiritual foundation for the College of New Jersey (Princeton, 1746), which was established by men who had been trained at the Log College or who were in sympathy with its endeavors. William's son, Gilbert, actively participated in the development of the College of New Jersey which was later renamed Princeton College (Princeton University).

Revival Blazes in Middle Colonies (1734-35)

The revival flames, which blazed in the Middle Colonies, spread to New England, where, through the influence of Congregational minister, Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), they were fanned into a blaze in 1734-35. From all indication, however, Edwards was unaware of the revival, which had begun among the Dutch Reformed and Presbyterians of the Middle Colonies. In 1741, Edwards delivered his most widely known sermon, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.

Whitefield Fans Revival (1739-41)

George Whitefield (1715-1770), associate of John and Charles Wesley, began his first preaching tour of America in 1739 and witnessed enormous success the following year in New England and the Middle Colonies. This in all, Whitefield made seven trips to America (1738, 1739-1741, 1744-1748, 1751-1752, 1754-1755, 1763-1765, 1769-1770), five of which were speaking tours.

Canada Experiences Revival (1775)

The Great Awakening spread to maritime Canada where it was nurtured by Henry Alline (1748-84) who was converted in 1775. During the Revolutionary War, he itinerated throughout Nova Scotia, establishing several Baptist and Congregational churches.

United Brethren "Great Meetings"

In the study of the history of the camp meeting, the revival efforts of the German-speaking peoples have almost been completely overlooked. In fact, these revivals, which were harbingers of the camp meeting, have been eclipsed in American church history. But given the fact that the United Brethren were so close in their fellowship with early American Methodists, the Great Meetings that prefigured the United Brethren in Christ Church are seminal in the life of the American camp meeting.

Following his conversion in 1761, a Mennonite in Byerland, Pennsylvania—Martin Boehm-began holding great meetings. These evangelistic meetings were attended by the Mennonites, Reformed, Lutherans, Moravians, Dunkers, and other religious groups from among the German and English speaking peoples. American church historians have overlooked the great meetings in their discussion of the rise of the camp meeting. These camp-meeting styled gatherings were similar to those that arose at the beginning of the nineteenth century. These great meetings would eventually give birth to the Church of the United Brethren in Christ (1800) and reflected features which would characterize the camp meeting movement:

These events were two and three day affairs with several hundred in attendance at times. They were held in barns, orchards, open air, and when possible in churches. ...

These meetings generated considerable enthusiasm. Excitement would move entire communities when they were held. Physical demonstrations, weeping, shouting, trembling, and trance-like states were common. Atheists and mockers were often stricken down, spreading fear throughout the whole communities.[9]

The term, Second Great Awakening, refers to a series of religious revivals that emerged in America in the late eighteenth century. It is distinguished from the Great Awakening that occurred in the 1730s and 1740s and continued until the beginning of the Revolutionary War. For the most part, the First Awakening was confined to New England and the Middle Colonies, but the Second Great Awakening knew few boundaries. Just as the two awakenings were geographically different, they also were different theologically. Calvinism dominated the First Awakening, while Arminianism carried the day in the Second Great Awakening. To more clearly understand the Second Great Awakening, its rise and progress has been organized under three interconnected phases. But before these phases are considered, the factors that led to the spiritual decline of America at the end of the eighteenth century must be considered.

The Roots of Spiritual Decline (1775-1781)

Between 1775 and 1781, the War of Independence was waged between the American colonies and Great Britain. The Calvinistic theology of the First Great Awakening paved the way for the American Revolution.[10] Calvinism denied the absolute authority of the monarch and espoused a republican form of government that suggested that all forms of government might be thrown off when it becomes unresponsive to the government of God himself.

Calvinistic theology mothered the War of Independence, and it was the Calvinists who were primarily responsible for its success. Pastors left their congregations, joining the Continental Army as soldiers or chaplains. In the end, Calvinistic denominations would be robbed of their patriarchs and left to totter along until a younger generation could fill the vacuum of the fallen patriots. This vacuum was not merely sensed within Calvinistic denominations, but was felt deeply within the spiritual and moral fiber of the young nation. Without sufficient spiritual leadership, America began a quick descent into an immoral abyss.

Seven years of war had a debilitating spiritual influence upon the American colonies. Methodists, who along with the Baptists were the most evangelistic, were losing nearly four thousand a year due to the spiritual lethargy which settled upon young America.[11]

As early as 1765, much of France had embraced infidelity due to the abuses of the Roman church in that country. Protestants were also treated with contempt. In the latter part of the eighteenth century, the American colonies experienced a dramatic disinterest in religion and morality. French infidelity swept through the colonies, threatening the spiritual life of the fledgling nation. Among those who drank most deeply from the wells of unbelief was Thomas Paine.

The New England Phase (1795)

Soon after becoming president of Yale College in 1795, Timothy Dwight, grandson of well-known revivalist Jonathan Edwards, embarked on a vigorous campaign to exterminate infidelity from the campus. In his class disputation on the question, "Is the Bible the Word of God," Dwight was influential in converting many students. Among Dwight's most able students was Lyman Beecher.[12]

Noah Webster, "America's schoolmaster," began to attend Yale in 1774 and graduated in 1778, after leaving school on two occasions to engage in the conflict with Britain. It seems that he returned to Yale during this revival and was greatly converted. The remainder of his life was a glowing example of evangelical Christianity.[13]

In 1795, eminent Massachusetts Baptist minister, Isaac Backus, and a host of other ministers called for churches to engage in the Concert of Prayer for a spiritual awakening. The first Concert of Prayer was held on the first Tuesday in January 1795, and continued once a quarter thereafter. The challenge was taken up by denomination after denomination, and revival began to break out throughout America.

Burned-Over District Phase Begins (1820s)

The Second Great Awakening began in the latter part of the eighteenth century and received an enormous surge of life through the ministry of Charles G. Finney (1792-1875). Converted in 1821, Finney was soon after greatly used of God to fan the flames of revival throughout the "Burned-Over District," an area of New York State bounded by the Catskill Mountains on the east and the Adirondack Mountains on the north. The following outline is a brief chronology of the ministry of Finney:

1823, (June 25) He was admitted to the St. Lawrence Presbytery.

1823, (December 30) Licensed to preach.

1824, (Spring) Finney was hired by the Female Missionary Society of the Western District to minister to the settlers of upstate New York.

1824, (July 1) Ordained. Under his ministry, a series of revivals erupted throughout Jefferson and St. Lawrence counties.

1825 By 1825, Finney's revival efforts had spread to the towns of Western, Troy, Utica, Rome, and Auburn. Here he exercised his "new measure," including the use of the anxious seat, protracted meetings, and the use of women to pray in public.

1827-32 Finney's revivals swept through urban centers such as New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, and Rochester.

1832-36 Became pastor of the Chatham Street Chapel (Second Free Presbyterian Church) in New York City.

1835 Accepted appointment as professor of theology at Oberlin College.

1836-37 Pastored the Broadway Tabernacle of New York City.

1837-72 Pastored the First Congregational Church of Oberlin, Ohio.

1849-50 In an effort to spark revivals across the Atlantic, Finney traveled to England.

1851-66 Served as president of Oberlin.

1859-60 Finney made a second evangelistic tour in England.

The third phase of the Second Great Awakening preceded the Burned-Over District phase and only slightly followed that wing begun by Timothy Dwight at Yale. The significance of this third phase and its residual influence will be considered at greater length in the following section: "The Rise and Progress of the Camp Meeting".

It may be noted that the well-known nineteenth-century American infidel, Robert Ingersoll, was the son of a Congregational minister, Rev. John Ingersoll, who helped fill Finney's pulpit while he was in Europe. For a short period, John Ingersoll ministered along side Finney. However, the bitterness shown toward Rev. Ingersoll by parishioners embittered Robert and made him the most formidable enemy of American Christianity in nineteenth-century America. In addition, Robert Ingersoll inadvertently helped to plant the seed for the writing of the Christian novel, Ben-Hur, which was written by Ingersoll's fellow Union soldier, General Lew Wallace.

Please click this box to read about Robert Ingersoll and the conversion of General Lew Wallace.The Rise and Progress of the Camp Meeting

Lincoln County Revival, NC (1791ff)

American church historians regard the Cane Ridge Revival (see below) as the beginning of the American camp meeting. But prior to Cane Ridge and the Cumberland Revival (see below), evidence of similar meetings occurred in North Carolina as early as 1791 and 1794 in Lincoln County, attended by both Presbyterians and Methodists. In 1795, a union camp meeting was convened in Bethel, North Carolina where hundreds were converted. The camp meeting became a powerful instrument of evangelism for the Methodists, but the Presbyterians, because of the excitement associated with them, soon repudiated their use.[14]

The Cumberland Revival (1797-1800)

This phase of the Second Great Awakening began among Presbyterians in the late 1790s. It was initiated in 1797 by a Presbyterian preacher by the name of James McGready who had moved to his three-point charge (Muddy River, Red River and Gasper River) in Logan County, Kentucky the previous year. Most of the people who lived in this area were refugees from all states in the Union who had fled here to avoid punishment for their crimes; they were murderers, horse thieves, highway robbers, and counterfeiters. For this reason, the area was nicknamed Rogues Harbour. McGready promoted prayer meetings every first Monday of the month among his churches, and asked his people to pray for him at sunset on each Saturday evening and again at sunrise Sunday morning. Soon after beginning his ministry in Logan County in 1797, McGready and his congregations were visited with revival, which continued, with some interruption, until 1800[15] when the revival became a great conflagration. Presbyterians soon united with Methodists in an effort to sustain the revival. In June 1800, John McGee, a Methodist preacher, and his brother William, a Presbyterian preacher, united with William Hodges, also a Presbyterian preacher, John Rankin, and McGready in a sacramental meeting on the banks of the Red River which lasted several days. On the final day, a mighty outpouring of God's Spirit came upon the congregation, the ground being covered with those under conviction, with their screams for mercy ascending to heaven. A significant development in the camp meeting experience occurred when participants began to bring provisions for several days to the meetings. From this practice, the American "camp meeting" arose.[16] Of this event, McGready writes,

But the year 1800 exceeds all that my eyes ever beheld upon earth. All that I have related is only, as it were, an introduction. Although many souls in these congregation, during the three preceding years, have been savingly converted, and now give living evidences of their union to Christ; yet all that work is only like a few drops before a mighty rain, when compared with the wonders of Almighty Grace, that took place in the year 1800.

In June the sacrament was administered at Red River. This was the greatest time we had ever seen before. On Monday multitudes were struck down under awful conviction; the cries of the distressed filled the whole house. There you might see profane swearers, and Sabbath-breakers pricked to the heart, and crying out, "what shall we do to be saved?" There frolickers and dancers crying for mercy. There you might see little children of 10, 11 and 12 years of age, praying and crying for redemption, in the blood of Jesus, in agonies of distress. During this sacrament, and until the Tuesday following, ten persons, we believe, were savingly brought home to Christ.

In July the sacrament was administered in Gasper River Congregation. Here multitudes crowded from all parts of the country to see a strange work, from the distance of forty, fifty, and even a hundred miles; whole families came in their wagons; between twenty and thirty wagons were brought to the place, loaded with people, and their provisions, in order to encamp at the meeting-house. On Friday nothing more appeared, during the day, than a decent solemnity. On Saturday matters continued in the same way, until in the evening. Two pious women were sitting together, conversing about their exercises; which conversation seemed to affect some of the by-standers; instantly the divine flame spread through the whole multitude. Presently you might have seen sinners lying powerless in every part of the house, praying and crying for mercy. Ministers and private Christians were kept busy during the night conversing with the distressed. This night a goodly number of awakened souls were delivered by sweet believing views of the glory, fullness, and sufficiency of Christ, to save to the uttermost. Amongst these were some little children-a striking proof of the religion of Jesus. Of many instances to which I have been an eyewitness, I shall only mention one, viz. a little girl. I stood by her whilst she lay across her mother's lap almost in despair. I was conversing with her when the first gleam of light broke in upon her mind-She started to her feet, and in an ecstasy of joy, she cried out, "O he is willing, he is willing-he is come, he is come-O what a sweet Christ he is—O what a precious Christ he is-O what a fullness I see in him—O what a beauty I see in him—O why was it that I never could believe! That I never could come to Christ before, when Christ was so willing to save me?" Then turning round, she addressed sinners, and told them of the glory, willingness and preciousness of Christ, and pled with them to repent; and all this in language so heavenly, and, at the same time, so rational and scriptural, that I was filled with astonishment. But were I to write you every particular of this kind that I have been an eye and ear witness to, during the two past years, it would fill many sheets of paper.[17]

Cane Ridge Revival (1801)

The Cane Ridge Revival of Bourbon County, Kentucky erupted in 1801 under the preaching of Presbyterian minister, Barton W. Stone. Impressed by the revivals of 1800, Stone organized similar meetings in his area of Cane Ridge, northeast of Lexington. A crowd of 12,500 attended in over 125 wagons, which also included people from Ohio and Tennessee. It is believed that nearly twenty-five thousand participants attended the weeklong event. Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist preachers formed themselves into preaching teams and spoke in different parts of the camp, all seeking the conversion of the unbeliever. James Finley, who subsequently became a Methodist circuit rider, was a witness to the revival:

The noise was like the roar of Niagara. The vast sea of human beings seemed to be agitated as if by a storm. I counted seven ministers, all preaching at one time, some on stumps, others in wagons and one standing on a tree which had, in falling, lodged against another . . ..

I stepped up on a log where I could have a better view of the surging sea of humanity. The scene that then presented itself to my mind was indescribable. At one time I saw at least five hundred swept down in a moment as if a battery of a thousand guns had been opened upon them, and then immediately followed shrieks and shouts that rent the very heavens.[18]

Methodism and the Camp Meeting

Explosive Use of Camp Meetings (1802ff)

The effects of the Cumberland Revival soon were felt throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, North and South Carolina, western Virginia and Pennsylvania, and the settled regions north of the Ohio River. By 1802, Methodist Bishop, Francis Asbury was mentioning the camp meetings frequently in his Journal; in 1811, Asbury noted that there were four hundred camp meetings held that year among the Methodist circuits. For at least three generations, the camp meeting was an instrument wielded by Methodism in the spread of the gospel.

Camp Meeting and Sanctification (1805)

Speaking of a camp meeting in Maryland in 1805, Asbury wrote, "Five hundred and eighty were said to be converted; and one hundred and twenty believers confirmed and sanctified. Lord, let this work be general."[19] The message of a pure heart and life was central to early American Methodism. In the nineteenth century, Methodism became the largest Protestant denomination in America, and under the influence of John Wesley's spiritual descendants and the doctrine of a pure heart and life, Methodism escorted America to new moral, spiritual, and social heights never previously known in any nation. The influence of the doctrine of Christian purity upon the moral life of America has been detailed by Johns Hopkins University scholar, Timothy Smith—in his book, Revivalism and Social Reform.[20]

Revival and the "Anxious Seat" (1806-1807)

During the winter of 1806-1807, a remarkable revival occurred in New York City that resulted in the accession of more than four hundred members to the Methodist Episcopal Church. With such large crowds, the front seats were vacated to allow workers to pray and converse with the remarkable number of seekers. The practice became so widely used among the Methodists that it was adopted by other evangelical denominations.[21]

Spreading the Message of a Pure Heart

About 1850, well-known evangelists, Walter and Phoebe Palmer, began to spend about half of each year at Methodist camp meetings and revivals advocating holiness. Hundreds of Methodist pastors professed the experience and returned to home to set their circuits aflame with the message of Christian purity.

When Daniel Wise assumed his post as editor of the periodical, Zion's Herald, in 1852, a strong emphasis was placed upon entire sanctification. Wise printed the testimonies of those preachers who had received the blessing of sanctification and praised camp meetings and revivals for their part in the spread of scriptural holiness.

In 1852, James Caughey awakened enthusiasm for holiness among Canadian Methodists. Walter and Phoebe Palmer later continued to stimulate the Canadians with the message of holiness. In 1857, the Palmers traveled to Canada where they noted that five to six thousand attended camps in Ontario and Quebec. In the fall of that year, a prayer meeting was stretched into a ten-day revival in which 400 were converted and scores were sanctified. In 1860, Methodist minister, Alfred Cookman, began to spend much of his summers preaching at Methodist camps in the East. Great success attended his preaching upon Christian purity of heart and life.

Decline of Camp Meeting in Methodism (1880s)

By 1880, the camp meeting within Methodism had changed significantly from its conception at the beginning of the century. Instead of the once familiar camp-meeting revival, religious services became increasingly interspersed with semi-religious or even secular subjects. Many of the campgrounds had replaced their tents with respectable middle-class resorts. With the decline of camp meetings and spiritual interests at the end of the nineteenth century, liberalism found a seedbed for its destructive influences in the early years of the twentieth century.

When Pilgrims and Puritans seeking religious freedom began to arrive in the New World, they began to evangelize the Indian children, and following the War of Independence, many Founding Fathers sought to secure the wellbeing of the American Republic by fostering the biblical principles of republicanism through the American Sunday School Union. The overwhelming majority of America's academic institutions were thoroughly Christian—including all of the Ivy League Schools. So abundant was the evidence in support of the fact that America had been birthed and developed by Christians that on February 29, 1892, the Supreme Court affirmed that America was a "Christian Nation."[22]

The camp meeting was only one of many institutions and agencies that American Christians used to advance the cause of Christ. Lamentably, many church leaders in denominations that have greatly benefited from the ministry of the camp meetings have in recent decades sought to destroy the camp meeting. In their place, they have failed to construct any similar institutions of comparable influence.

With Muslims seeking to employ every opportunity available to them to advance their bloody religion, may God give the Christian Church around the world leaders who will build the Church, instead of destroying it from within. God does not intend for the Christian Church to lose in the battle against evil anymore than He intended for Israel to lose!

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] See the Pew Research study, "America's Changing Religious Landscape" (http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/, May 23, 2015).

[2] Boehm, Boehm's Reminiscences, Historical and Biographical, 401.

[3] Hoen's understanding of the Eucharist has been influenced by Wessel Gansfort (ca. 1420-89) and his work, On the Sacrament of the Eucharist. McGrath, Reformation Thought, 173.

[4] Schmidt, Holy Fairs, 49-50.

[5] Schmidt, Holy Fairs, 53-54.

[6] Gilbert Tennent had moved to New Brunswick, New Jersey in 1725. His contact with Frelinghuysen may have occurred as early as 1726.

[7] The exact date the Log College started is not known. Some date it as early as 1726 while others date it as late as 1735.

[8] Gilbert Tennent's sermon, "The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry," preached at Nottingham, Pennsylvania on March 8, 1740, contributed to the spirit of animosity that contributed to the first split in the Presbyterian Church. In 1758, the schism was breached between the two parties, thanks to Gilbert Tennent's call for unity.

[9] Fetters, Trials and Triumphs, 44.

[10] The following dates chronicle the significant developments related to the Revolution:

1775, The first battles of the American Revolution were waged at Lexington and Concord. General George Washington was named Commander in Chief.

1776, In June 1776, the Continental Congress drafted the Declaration of Independence and was subsequently adopted on July 4.

1777, General George Washington defeated British commander, Cornwallis, at Princeton. The American army suffered a very difficult winter at Valley Forge encampment.

1778, Americans gained foreign support in its struggle with England when France officially recognizes the colonies' independence and intervened on behalf of the Americans.

1781, British general, Cornwallis, was forced to surrender on October 19, 1781 after having been forced to retreat to the south as thousands of French troops arrived to assist the Americans.

1782, The British Cabinet formally recognized the independence of the American colonies.

1783, The Treaty of Paris was signed between the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain.

[11] Orr, The Eager Feet, 1-12.

[12] See Lyman Beecher, Autobiography (1865).

[13] See, Noah Webster, "Advice to the Young," in History of the United States (New Haven: Durrie and Peck; Baldwin and Treadaway, Printers, 1832; reprint, Noah Webster's Advice to the Young and Moral Catechism, Aledo, TX: WallBuilder Press, 1995).

[14] Beardsley, American Revivals, 193.

[15] The revival 1797 to 1800 is remembered as the Logan County or Cumberland revival.

[16] The Cane Ridge revival of Bourbon County, Kentucky arose in 1801 under the preaching of Presbyterian minister, Barton W. Stone.

[17] James Smith, ed., Posthumous Works of the Reverend and Pious James M'Gready, Minister of the Gospel, in Henderson, Kentucky (Louisville, KY: W.W. Worsley, 1831; http://www.cumberland.org/hfcpc/McGreaBK.htm, March 12, 2003).

[18] Pratney (1994:104; http://www.pastornet.net.au/renewal/fire/ff-1800.htm, March 12, 2003).

[19] Peters, Christian Perfection, 97.

[20] Timothy L. Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform (1957).

[21] Beardsley, American Revivals, 194-95.

[22] See "Supreme Court Declares America a Christian Nation," Christian Heritage Fellowship (https:/supreme-court-declares-america-christian/).