When the United States Capitol Was a Church

Thousands of pieces of evidence exist that deny that America was founded as a secular nation. One reason the denial of America's Christian history has been so successful is because it has waged war against America's true Christian heritage for nearly a century. During this time, secularism has denied, denounced, and defamed America's Christian heroes and heroines and their heroic acts. By denying the truth, they have advocated error and half-truths. One of the greatest challenges facing Christian leaders in twenty-first-century America is the rediscovery and articulation of the Christian heritage bequeathed to America by its Founding Fathers and their faithful descendants.When the United States Capitol Was a Church

America's Christian heritage has been written in both large, bold, declarative statements as well as faint ornamental affirmations. To the degree that secularists and their supporters are successful in concealing the truth, to that degree America will walk in the darkness brought upon it and every nation where irreligion has ascended to tyrannical dominance. One of the many ways that America's Founding Fathers declared their intentions was not only through the principles they articulated in their writings, but the practices they observed, and few practices are as straightforward as the way they worshipped. If it may be demonstrated that their worship was Christian and that they intended that this worship should not be excluded from the recognition and appreciation of the government, the fraudulent claims of secularism are completely denied, and therefore, must be denounced by an accurately informed people. The misinformation and fraudulent claims of secularism against America's Christian heritage suffer a grievous blow when we realize that America's Founding Fathers established a church within the United States Capitol before its construction was complete, and the Capitol continued to be used as a Church until after the Civil War.When the United States Capitol Was a Church

The subject addressed in this article is discussed at greater length in When the United States Capitol Was a Church. Christian Heritage Fellowship would be honored to work with individuals, businesses, churches, institutions, or organizations to help communicate the truth concerning the positive influence of the Christian faith by providing bulk pricing: Please contact us here... To purchase a limited quantity of this publication, please click: Purchase here...

Article Contents

Capitol Houses Church Before Congress

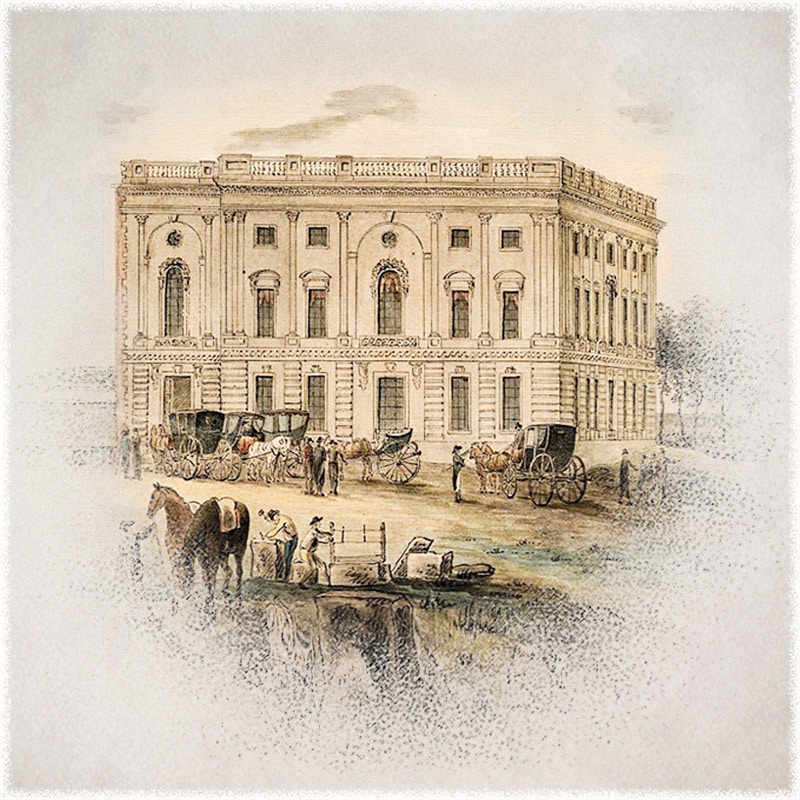

Before the United States Capitol was used by the Senate or House of Representatives, it was used as a church—or perhaps more accurately as churches. In his plans for America's new capital, Peter L'Enfant chose Jenkins Hill as the site for the Capitol building, and on September 18, 1793, President Washington laid the cornerstone for the new Capitol.[1] In June 1795—less than two years after the beginning of construction—a church began to meet at the emerging Capitol building. The Federal Orrery, a Boston newspaper, carried the story in its July 2, 1795 edition:

City of Washington, June 19. It is with much pleasure that we discover the rising consequences of our infant city. Public worship is now regularly administered at the Capitol, every Sunday morning, at 11 o'clock by the Reverend Mr. Ralph.[2]

One reason the Capitol was used as a church was that the land area selected for the nation's new capital was not yet developed and populated. While some secularists seize every opportunity to deny this evidence of America's Christian heritage, the historical accounts describing worship in the Capitol are too numerous to be disregarded or discounted. For example, Senator John Quincy Adams explained why the Capitol was used as a church. In 1803 after Congress had taken up residence in Washington at the Capitol, he noted the persistent issue that gave rise to the use of the Capitol as a church, saying: "There is no church of any denomination in this city."[3] For a number of years after Congress located in Washington, there were only two small churches, but by 1837, more than twenty churches had been built.[4]

Congress Officially Sanctions Church

A church had been meeting in the United States Capitol for more than five years before Congress officially occupied the Capitol. The first session of both houses of Congress at the Capitol began on November 17, 1800.[5] During the first few weeks, committee room assignments and other designations for the use of the Capitol were made. It was during this period of allotting rooms and space throughout the Capitol, that the larger chamber of the House of Representatives was officially designated as the place where church services would be held. With no debate, the House of Representatives—by consensus—made provision for the use of their chamber for Christian worship services. No other building at that time in Washington was sufficient to accommodate the large crowd that attended worship at the Capitol, and the chamber of the House of Representatives was the largest room in the Capitol. The Annals of Congress records the ease with which Christian worship was officially sanctioned in the Capitol. On Thursday, December 4, 1800, a brief entry was made in this official record of the House of Representatives which read:

The Speaker informed the House that the Chaplains had proposed, if agreeable to the House, to hold Divine service every Sunday in their [the House of Representatives']Chamber.[6]

The fact that the church in the Capitol was attended by those whom secularists depend upon for their twisted interpretation of "separation of church and state" is a fatal blow to them and their liberal judges throughout America. Thomas Jefferson faithfully attended the Capitol church, both as Vice-President[7] and President.[8] On January 1, 1802, Jefferson responded to the letter from the Danbury Baptists affirming the intention of the First Congress when it proposed the wording for the First Amendment to the Constitution. Since most of the thirteen original states already had state churches or a denomination that they preferred over other Christian denominations, they did not wish to give the federal government the right to establish another federal denominational church over the ones already established within their own states. Eleven of the thirteen states already had their own denominational churches,[9] and the Danbury Baptists wished to make sure that President Jefferson would not use the federal government to establish a state church over the entire nation as had been done with Anglicanism in England and other denominations in other nations. In his letter, Jefferson assured the Baptists that he would keep the federal government from establishing a federal church, saying,

I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their [federal]legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion [or specific Christian denomination], or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and state [or federal government].[10]

By quoting above the First Amendment in his response to the Danbury Baptist, Jefferson was saying he was going to be faithful to the intent of the First Amendment not to establish a federal denomination, nor to prohibit "the free exercise" of religion. That Jefferson meant that he would have no part in establishing one Christian denomination over all others to make a state church is made plain by a letter Jefferson sent to fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush. In his letter, Jefferson maintains the same opinion on this subject as the First Congress that composed the First Amendment. His letter emphasizes his own resolve to resist the desires of certain denominational clergy to secure recognition of their denominations as the federal or national church. In his letter, Jefferson wrote:

…the clause of the Constitution [or the First Amendment]which, while it secured the freedom of the press, covered also the freedom of religion, had given to the clergy a very favorite hope of obtaining an establishment of a particular form [or denomination]of Christianity through the United States [federal government]; and as every sect [of Christians]believes its own form the true one, every one perhaps hoped for his own [denomination to be preferred], but especially the Episcopalians and Congregationalists. The returning good sense of our country threatens abortion to their hopes and they believe that any portion of power confided to me will be exerted in opposition to their schemes [to establish a denominational federal church]. And they believe rightly.[11]

Jefferson's "wall of separation" was nothing more than what was guaranteed by the First Amendment, that the federal government would not establish a state church. And, if Jefferson had meant that government should not in any way allow itself to be influenced by the Christian faith, his practice as governor of Virginia and President of the United States was at complete variance with this principle, because Jefferson participated in Christian practices while in these offices! To interpret "separation of church and state" as it has been interpreted since 1947 makes Jefferson out to be a hypocrite—because this interpretation insists he taught religion should be excluded from the public life of the state, and yet, Jefferson himself participated in and endorsed Christian practices between Christianity and the state. However, to interpret this expression as Jefferson and all other Founding Fathers did—that they would not establish a federal denomination—allows Jefferson to participate in the Christian and state relationships that he observed without being a hypocrite!

Until 1947, American courts had interpreted the Constitution as Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers had both intended and practiced themselves at state and federal levels. What completely exposes this error of uninformed liberal judges is the fact that if Jefferson had intended that Christianity should exercise no influence upon the state, conscience would have prevented him from attending Christian worship in the Capitol on January 3, 1802, two days after he had penned his letter to the Danbury Baptists.[12] What is more, Jefferson was not hesitant or shy about his understanding of the relationship of government to Christianity, especially his attendance of the Capitol church. Eyewitness accounts further relate that President Jefferson took his entire family to church with him,[13] that he was faithful in attendance there—including during some of the most inclement weather,[14] and that he had reserved seating at the Capitol church.[15]

President Jefferson's successor to the presidency, James Madison, also attended the Capitol church. The difference between the two men was distinct as was the way that each arrived at church. In an exhibition presented by the Library of Congress, the difference between the two Presidents was highlighted:

Within a year of his inauguration, Jefferson began attending church services in the House of Representatives. Madison followed Jefferson's example, although unlike Jefferson, who rode on horseback to church in the Capitol, Madison came in a coach and four.[16]

From the time of Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln, many of the presidents worshipped at the church in the Capitol.[17] The marine band was engaged to play for the services, but after a time, the band was dismissed, owing to the fact that their brilliant red attire was too ostentatious.[18]

Following the same spirit that had characterized Congress from its inception in 1774 at the First Continental Congress, worship services at the Capitol were interdenominational and were orchestrated by the chaplains appointed by the House of Representatives and Senate. Sermons were preached by the chaplains on a rotating basis or delivered by visiting ministers. One Washington resident who attended services in the Capitol recounted some of these specifics, saying,

Not only the chaplains, but the most distinguished clergymen who visited the city, preached in the Capitol. . . .

Preachers of every sect and denomination of Christians were there admitted—Catholics, Unitarians, Quakers with every intervening diversity of sect. Even women were allowed to display their pulpit eloquence, in this national Hall.[19]

When the government moved from Philadelphia to Washington, services were conducted from 1800 to 1801 in the "hall" of the House of Representatives—in the north wing of the building. From 1801 to 1804, the main service in the Capitol was conducted in the south wing, before returning to the north wing until 1807. From 1807 to 1857, services were held in what is now called Statuary Hall,[20] by which time the congregation numbered nearly 2000 and was the "largest Protestant Sabbath audience then in the United States."[21]

The Capitol church was so successful that capacity crowds could be expected to attend services there. Members of Congress regularly gave up their seats to others. Space was in such short supply "that [when]the floor of the house offered insufficient space, the platform behind the Speaker's chair, and every spot where a chair could be wedged in was crowded with ladies . . . and their attendant beaux and who led them to their seats."[22]

With such large audiences, provision was made in other areas of the Capitol for additional services. In his journal for October 23, 1803, Senator John Quincy Adams recounted: "I went both forenoon [to morning worship]and afternoon [to evening worship]to the Treasury."[23] But, the Treasury Office was not the only additional space in the Capitol being used for worship. Researchers at the Library of Congress also report that the Supreme Court Chamber (then in the Capitol)[24] and the Senate Chamber were also used for worship.[25]

Not only were there multiple nondenominational services that were held at the Capitol provided for by the chaplains of Congress, but in time, denominational services were also held at the Capitol before their respective churches were built in the city. Capitol Hill Presbyterian, First Congregational Church, First Presbyterian Church and others initially met each week for their own services at the Capitol. It was not uncommon to have as many as four denominational services at the Capitol in addition to the nondenominational services.[26] The construction of local denominational churches eventually depleted the attendance of the nondenominational churches at the Capitol, and eventually, services at the Capitol were discontinued in the years that followed the Civil War.

While the Continental Congress and the United States Congress were located in Philadelphia, Christ Church—known as "The Nation's Church"[27]—exercised vital support to the nation's first legislators. That the Capitol was first used as a church for Christian worship only continued the spiritual camaraderie that had already been experienced by the Continental Congress.

The example of America's Founding Fathers demonstrates that they never intended the skewed interpretation of the First Amendment that many judges have rendered since 1947. The example of President Jefferson and all other Founding Fathers clearly demonstrate that they expected that Christianity should exercise a moral influence upon the legislative process of the federal government. For nearly three quarters of a century, Christian worship was conducted in the United States Capitol, and the fact that Presidents Jefferson and Madison—and succeeding generations of presidents—had so thoroughly participated in these services has led scholars at the Library of Congress to conclude,

It is no exaggeration to say that on Sundays in Washington during the administrations of Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809) and of James Madison (1809-1817) the state became the church.[28]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] "United States Capitol," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Capitol, December 22, 2015).

[2]Federal Orrery (Boston, July 2, 1795), 2; Also see David Barton, "Church in the U.S. Capitol," WallBuilders (http://www.wallbuilders.com/libissuesarticles.asp?id=90, December 22, 2015) and Randy Russ, It's Separation of Church and State, Not Divorce (n.p.: Randy Russ, 2010), 53. For additional information, see Library of Congress, "The State Becomes the Church: Jefferson and Madison," Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: Religion and the Federal Government, Part 2 (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06-2.html, December 22, 2015).

[4] Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, Portrayed by the Family Letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard) from the Collection of Her Grandson, J. Henley Smith, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1906), 16.

[5] "United States Capitol," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Capitol, December 23, 2015).

[6]The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States with an Appendix Containing Important State Papers and Public Documents and All the Laws of a Public Nature (Washington [D.C.]: Gales and Seaton, 1855), 797.

[7] This fact is noted in a letter of Bishop Thomas Claggett, February 18, 1801, which verified that Jefferson attended worship as Vice President in the House of Representatives. Available in Maryland Diocesan Archives.

[8] In a letter, January 4, 1802, Rev. Manasseh Cutler indicates Jefferson attended church at the Capitol for the first time, but this only could mean first time as President given the fact his attendance was already established. See William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler, Life, Journals and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, Ll. D (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke and Co., 1888), 2:66.

[9] Charles B. Galloway, Christianity and the American Commonwealth: The Influence of Christianity in Making This Nation, Reprint ed. (Powder Springs, Georgia: American Vision, 2005), 111.

[10] “The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827; Thomas Jefferson to Danbury, Connecticut, Baptist Association, January 1, 1802, The Library of Congress (http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib010955, October 13, 2013); also see “Jefferson’s Wall of Separation Letter,” Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/tj/sep_church_state.htm, October 13, 2013).

[11] "From Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 23 September 1800," National Archives, Founders Online (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-32-02-0102, October 13, 2013).

[12] See Cutler and Cutler, Life of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, 2:66.

[13] Cutler and Cutler, Life of Rev. Manasseh, 2:113, 119.

[14] Cutler and Cutler, Life of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, 2:114.

[15] Smith, First Forty Years of Washington Society, 13.

[16] "The State Becomes the Church: Jefferson and Madison," Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: Religion and the Federal Government, Part 2 (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06-2.html, December 22, 2015).

[17] David Barton, "Church in the U.S. Capitol," WallBuilders (http://www.wallbuilders.com/libissuesarticles.asp?id=90, December 22, 2015).

[18] Margaret Bayard Smith observed: "The marine-band, were the performers. Their scarlet uniform, their various instruments, made quite a dazzling appearance in the gallery. The marches they played were good and inspiring, but in their attempts to accompany the psalm-singing of the congregation, they completely failed and after a while, the practice was discontinued,—it was too ridiculous." Smith, First Forty Years of Washington Society, 14.

[19] Ibid., 14-15.

[20] "The State Becomes the Church: Jefferson and Madison," Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: Religion and the Federal Government, Part 2 (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06-2.html#obj170, December 24, 2015).

[21] "The State Becomes the Church: Jefferson and Madison," Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: Religion and the Federal Government, Part 2 (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06-2.html#obj180, December 22, 2015).

[22] Smith, First Forty Years of Washington Society, 14.

[23] Adams, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, 1:265.

[24] James H. Hutson and Jay I. Kislak Reference Collection (Library of Congress), Religion and the Founding of the American Republic (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1998), 90.

[25] David Barton, "Church in the U.S. Capitol," WallBuilders (http://www.wallbuilders.com/libissuesarticles.asp?id=90, December 22, 2015).

[26] David Barton, "Church in the U.S. Capitol," WallBuilders (http://www.wallbuilders.com/libissuesarticles.asp?id=90, December 22, 2015).

[27] Catherine Millard, The Rewriting of America's History (Camp Hill, PA: Horizon House Publishers, 1991), 259.

[28] "The State Becomes the Church: Jefferson and Madison," Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: Religion and the Federal Government, Part 2 (http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06-2.html, December 22, 2015).

The United States Capitol Was a Church