Washington Believed God Provided for America

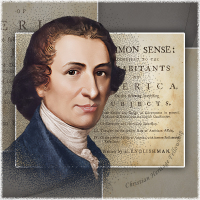

One of the surest means of refuting claims that America's Founding Fathers were not Christian is the realization and proclamation of the fact that they believed God birthed America through His providence. They believe God orchestrated the independence of America, and the Father of our nation, George Washington, was among those who affirmed this Christian teaching.Since the 1920s and following, secularists have been attempting to reshape American history to conform to their worldview in an attempt to displace the Christian worldview upon which America was founded. Because the Church in America has failed to accurately teach the truth concerning the origin of the nation, these attempts by secular humanists, atheists, agnostics, and other irreligionists have enjoyed significant political, academic, legal, and social reward for their efforts. Following the example of the Father of Lies, secularists have deceived Americans for nearly one hundred years by denying the Christian commitments of the overwhelming majority of America's Founding Fathers. While numerous examples could be readily produced to rob secularists of their efforts to de-Christianize George Washington, only several quotes are sufficient to exonerate him of the charge of Deism.Washington Believed God Provided for America

Contents

English Deism was the first step to present-day radical liberalism[1] and cloaked its deceptive nature under the romantic designation, "the natural religion." In 1624, Edward Herbert (1583-1648), Lord of Cherbury, gave shape to the basic tenets of Deism. In his work De Veritate, Prout Distinguitura Revelatione, he proposed that religion should consist of the principles that were rational, without depending upon Scripture.[2] The most important principles of Deism that present-day secularists allege America's Founding Fathers held may be summarized as follows: Washington Believed God Provided for America

God does exist, contrary to the principles of atheists;

God created the world, but since creation has had nothing to do with what He created;

Christian and other religious claims that God spoke through prophets and sent a Savior to the world are in error since God has nothing to do with creation;

Since God has nothing to do with what He created, He does not care for it through providence.[3]

Secondary Affirmation of Providence

The evidence to support George Washington's faith far outweighs any alleged evidence to the contrary. Against the claims of Deism, Washington clearly believed—like all Christians—God had not removed Himself from providential care and involvement of the world. The letters and diaries of George Washington clearly depict a man who had received a Christian education and one who practiced his faith. The doctrine of divine providence was prominent in colonial America and the fledgling nation that followed. As noted below in the following quotes, George Washington believed that God was providentially at work in his life—guiding the world to a divinely appointed end.

The Indian Prophecy

On July 9, 1755, the Battle of the Monongahela (also known as the Battle of the Wilderness) was one of the first battles of the French and Indian War. It was waged between the French and their Indian allies on one side and the British, led by General Edward Braddock, and their colonial supporters on the other. Ordered to take Fort Duquesne from the French, General Braddock neared the fort before engaging the French and Indians at Braddock's Field in what is now Braddock, Pennsylvania, ten miles east of present-day Pittsburgh. Of the nearly 1,300 soldiers Braddock led into battle that day, 456 were killed on the field and 422 were wounded. During the battle, Indian war cries and the sight of the scalps of their fallen comrades nailed to trees terrorized the English and colonials. General Braddock was mortally wounded during the battle and died several days later. Colonel George Washington survived a hail of bullets,

...four balls pierced his coat, and several grazed his sword; every other officer [nearby] was either killed or wounded, and he alone remained unhurt.[4]

The diaries of Washington[5] reveal that fifteen years after the Battle of Monongahela, Washington and his friend and personal physician, Dr. James Craik, returned to the area of Fort Duquesne. Following the French and Indian War, Washington and his soldiers had received lands in payment for their services during the war, and it was the security of those lands that drew him back to Western Pennsylvania. Near the field of battle, they encountered several Indians, the details of which were subsequently related to Washington's adopted grandson, George Washington Parke Curtis, by Washington's friend and physician, Dr. Craik who had been an eye-witness. Washington's adopted grandson Parke Curtis (also the father-in-law of Robert E. Lee) in turn recorded the event related to him by Dr. Craik in his book, Recollections of Washington:

It was in 1770, that Colonel Washington, accompanied by Doctor James Craik, and a considerable party of hunters, woodsmen, and others, proceeded to the Kanawha with a view to explore the country, and make surveys of extensive and valuable bodies of lands. At that time of day, the Kanawha was several hundred miles remote from the frontier settlements, and only accessible by Indian path, which wound through the passes of the mountains.

In those wild and unfrequented regions, the party formed a camp on the bank of the river, consisting of rudely-constructed wigwams or shelters, from which they issued to explore and survey those alluvial tracts, now forming the most fertile and best inhabited parts of the west of Virginia.

This romantic camp, though far removed from the homes of civilization, possessed very many advantages. The great abundance of various kinds of game in its vicinity afforded a sumptuous larder, while a few luxuries of foreign growth, which had been brought on the baggage horses, made the adventurers as comfortable as they could reasonably desire.

One day when resting in camp from the fatigues attendant on so arduous an enterprise, a party of Indians led by a trader, were discovered. No recourse was had to arms, for peace in great measure reigned on the frontier; the border warfare which so long had harassed the unhappy settlers, had principally subsided, and the savage driven farther and farther back, as the settlements advanced, had sufficiently felt the power of the whites, to view them with fear, as well as hate. Again, the approach of this party was anything but hostile, and the appearance of the trader, a being half savage, half civilized, made it certain that the mission was rather of peace than war.

They halted at a short distance, and the interpreter advancing, declared that he was conducting a party, which consisted of a grand sachem, and some attendant warriors; that the chief was a very great man among the northwestern tribes, and the same who commanded the Indians on the fall of Braddock, sixteen years before, that hearing of the visit of Colonel Washington to the Western country, this chief had set out on a mission, the object of which himself could make known.

The colonel [Washington] received the ambassador with courtesy, and having put matters in camp in the best possible order for the reception of such distinguished visitors, which so short a notice would allow, the strangers were introduced. Among the colonists were some fine, tall, and manly figures, but so soon as the sachem approached, he in a moment pointed out the hero of the Monongahela, from among the group, although sixteen years had elapsed since he had seen him, and then only in the tumult and fury of battle. The Indian was of a lofty stature, and of a dignified and imposing appearance.

The usual salutations were going round, when it was observed, that the grand chief, although perfectly familiar with every other person present, preserved toward Colonel Washington the most reverential deference. It was in vain that the colonel extended his hand, the Indian drew back, with the most impressive marks of awe and respect. A last effort was made to induce an intercourse, by resorting to the delight of the savages—ardent spirit—which the colonel having tasted, offered to his guest; the Indian bowed his head in submission, but wetted not his lips. Tobacco, for the use of which Washington always had the utmost abhorrence, was next tried, the colonel taking a single puff to the great annoyance of his feelings, and then offering the calumet to the chief, who touched not the symbol of savage friendship. The banquet being now ready, the colonel did the honors of the feast, and placing the great man at this side, helped him plentifully, but the Indian fed not at the board. Amazement now possessed the company, and an intense anxiety became apparent, as to the issue of so extraordinary an adventure. The council fire was kindled, when the grand sachem addressed our Washington to the following effect:

I am a chief and ruler over my tribes.[6] My influence extends to the waters of the great lakes and to the far blue mountains. I have traveled a long and weary path that I might see the young warrior of the great battle. It was on the day when the white man’s blood mixed with the streams of our forests that I first beheld this chief: I called to my young men and said, mark yon tall and daring warrior? He is not of the red—coat tribe—he hath an Indian’s wisdom, and his warriors fight as we do—himself alone exposed. Quick, let your aim be certain, and he dies. Our rifles were leveled, rifles which, but for you, knew not how to miss—‘twas all in vain, a power mightier far than we, shielded him from harm. He cannot die in battle. l am old and soon shall be gathered to the great council fire of my fathers in the land of shades, but ere I go, there is something bids me speak in the voice of prophecy: Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man, and guides his destinies—he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire.

The savage ceased, his oracle delivered, his prophetic mission fulfilled, he retired to muse in silence, upon that wonder—working spirit, which his dark “Untutored mind saw oft in clouds, and heard Him in the wind.” Night coming on, the children of the forest spread their blankets and were soon buried in sleep. At early dawn they bid adieu to the camp, and were seen slowly winding their way toward the distant haunts of their tribe. The effects which this mysterious and romantic adventure had upon the provincials, were as various as the variety of character which composed the party. All eyes were turned on him, to whom the oracle had been addressed, but from his ever-serene and thoughtful countenance, nothing could be discovered: still all this was strange, “t’was passive strange.” On the mind of Doctor James Craik, a most deep and lasting impression was made, and in the war of the Revolution it became a favorite theme with him particularly after any perilous action, in which his friend and commander had been peculiarly exposed, as the battles of Princeton, Germantown, and Monmouth. On the latter occasion, as we have elsewhere observed, Doctor Craik expressed his great faith in the Indian’s prophecy.[7]

Candor requires us to recognize that this testimony of divine providence in the life of George Washington was secondary, but the following primary quotes (to which many others may be added) should leave no doubt that secular deistic denial of divine providence was far from the mind of the Father of our nation.

Primary Affirmation of Providence

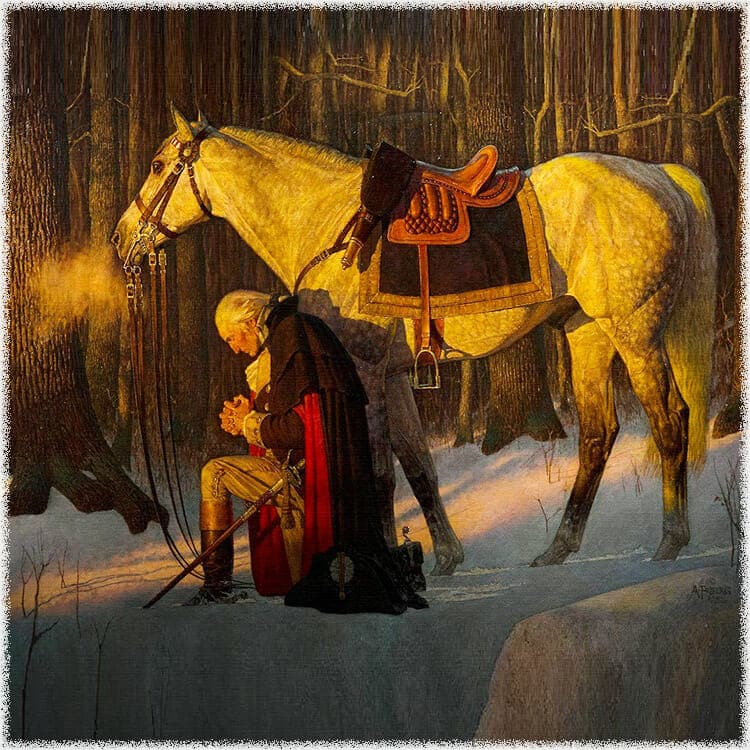

Washington was very much aware of the providence—the care—of God in his life. Experiencing the hazards of the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and the military action of the American War of Independence (1775-1783), he had often been exposed to harrowing experiences that nearly claimed his life. While the above secondary affirmation of God's care of Washington may be regarded as confirmation, his own confession of the intervention of God in his life for a divine cause is of critical interest. As the War of Independence was in its infancy, he wrote, on January 14, 1776, to the president of the Continental Congress acknowledging God's providence in the national interest of Washington and America:

I have often thought how much happier I should have been, if, instead of accepting of a command under such circumstances, I had taken my musket on my shoulder and entered the ranks, or, if I could have justified the measure to posterity and my own conscience, had retired to the back country, and lived in a wigwam. If I shall be able to rise superior to these and many other difficulties, which might be enumerated, I shall most religiously believe, that the finger of Providence is in it, to blind the eyes of our enemies.[8]

As the war neared a conclusion, he wrote to his brother, Lund, on May 19, 1780, affirming his confidence in God's care and provision toward Washington and the American cause:

Providence, to whom we are infinitely more indebted than we are to our own wisdom, or our own exertions, has always displayed its power and goodness, when clouds and thick darkness seemed ready to overwhelm us. The hour is now come when we stand much in need Of another manifestation of its bounty however little we deserve it.[9]

No true Deist believes that God is concerned about the world He has created. Washington fully believed that God was shaping the events of his life and the events of the life of his nation!

Conclusion: Washington Was a Christian

Because secularism has had no appreciable place in American history until recent decades, secularists have no appreciable influence in the life of the nation. As a result, for nearly a century secularists have been attempting to rewrite American history in their own image—including the legacy of the Father of America. All that is necessary to demonstrate that Washington was not a Deist is to show that he believed God was active in the world. As a result, he would affirm what he was taught as a boy and showed no sign of relinquishing, that God did indeed speak through the prophets and in a variety of ways, but has spoken most clearly in the advent of his Son, Jesus Christ (Hebrews 1:1-2).

Should Christians and the Church in America fail to rehearse the truth concerning America's godly Christian heritage, Deists and the secularists will reshape it according to a worldview that has always brought pain and suffering to humanity. As Dr. Peter Lillback has said,

Washington never declared himself to be a Deist, and he did declare himself to be a Christian.[10]

In this era of national crisis, Christians must evidence a similar courage to declare themselves to be followers of Christ and proudly declare the Christian heritage that has been bequeathed to us!

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] It is evident that before Deism emerged in England, Naturalism in France, or Rationalism in Germany, Holland had greatly influenced its neighbors to the south and west through Rene Descartes, Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677), and Pierre Bayle (1647-1706). In England, John Locke and Alexander Pope, “the prince of rhyme and the grand poet of reason,” became sounding boards for the Dutch thinkers. Such was the beginning of theological liberalism in England. Subsequently, the books of the “free-thinkers” in England were devoured by the Germans, who being restrained by the principles of the Lutheran Reformation, were slower to respond to the new form of thought. Neve, Christian Thought, 2:66.

[2]Edward Herbert's main principles included the following: God does exist; Man is dependent upon God and is obligated to reverence God; piety or morality is the harmonization of the human faculties; there exists a difference between good and evil; there exists a future state of rewards and punishment. See Hodge, Systematic Theology, 1:42.

[3] Though Deism had been dealt enormous blows by William Law (1732, Case of Reason) and Joseph Butler (1736, Analogy of Religion), it flourished until about the time of the death of deist David Hume (1711-1776). Hume attacked biblical miracles. German Rationalism, English Deism, and French Naturalism were all efforts at explaining the world in naturalistic terms.

[4] Anna C. Reed, The Life of Washington (Green Forest, AR: Attic Books, 2010), 38. This work is a reprint of the original 1842 publication by the American Sunday School Union, now known as American Missionary Fellowship.

[5] John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Diaries of George Washington: Vol. 1:1748-1770 (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company), see September 20, 1770ff.

[6] The Indian image is an interpretation of Chief Pontiac, painted by John Mix Stanley (The Granger Collection, New York). Though the Indian discussed in this anecdote is not named, it is very likely that Chief Pontiac was among those who fought against General Braddock in the Battle of the Monongahela. See "The Indian's Prophecy," Have You Forgotten Providence? (http://gwprovidence.com/gwprovidence.com/?p=30; February 17, 2014).

[7] George Washington Parke Curtis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington, by His Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Curtis, with a Memoir of the Author by His Daughter, and Illustrative and Explanatory Notes by Benson J. Lossing (Philadelphia: J. W. Bradley, 1861), 300-305; cited by Peter Lillback, George Washington's Sacred Fire (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Providence Forum Press, 2006), 162-165.

[8] John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 ([Washington]: Published by the authority of Congress, 1931-44), 4: 1-14-1776.

[9] Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of George Washington, 18: 5-19-1780.

[10] Lillback, George Washington's Sacred Fire, 143.