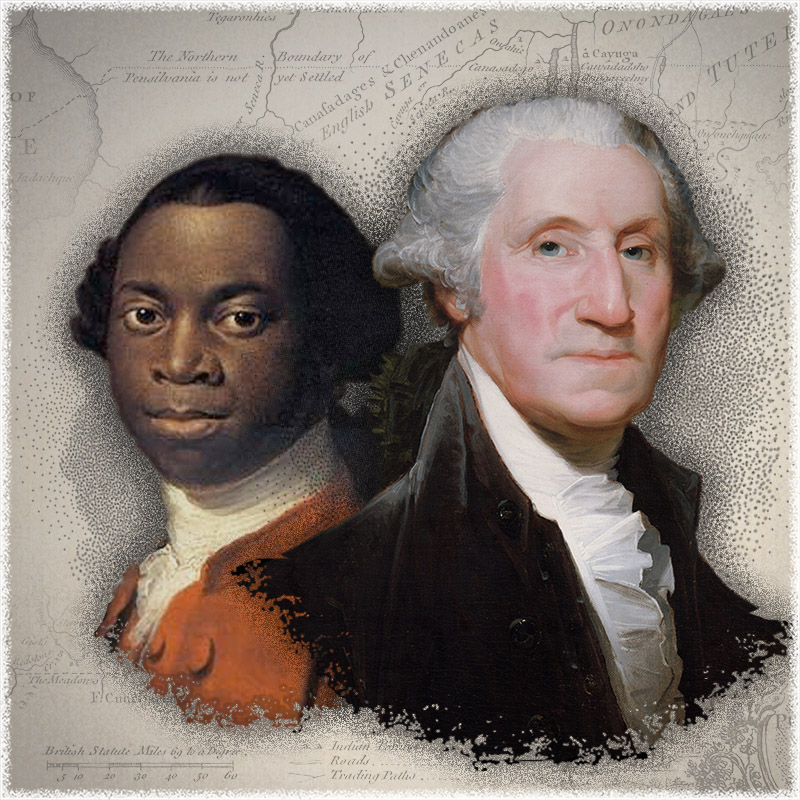

George Washington and Primus Hall

William Cooper Nell (December 16, 1816 – May 25, 1874) was an African-American author, abolitionist, civil servant, and publisher of Boston, Massachusetts. As a prodigious writer and publisher, Nell penned important works concerning the contributions of black soldiers in the War of Independence and War of 1812. Those works include, Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851) and The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855), which were the first works of their kind concerning African Americans. George Washington and Primus Hall

In the appendix of his book, Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812, Nell inserted an anecdote which was originally published in Godey’s Lady’s Book, June, 1849, which was written by Rev. Henry F. Harrington. The anecdote concerned General George Washington and the black steward of Colonel Timothy Pickering, who was named Primus Hall. George Washington and Primus Hall

Colonel Timothy Pickering (1745-1829) began a legal career in Massachusetts after graduating from Harvard. Pickering served as an officer in the American Revolutionary Army in the Siege of Boston and the early stages of the American Revolution. Later in the War, he served as Adjutant General and Quartermaster General of the Continental Army.

Following the American Revolution, Pickering participated in the 1787 Pennsylvania convention to ratify the United States Constitution. In 1791, President Washington appointed him as Postmaster General, and after a brief stint as Secretary of War, he was appointed as Secretary of State in 1795, an office he held until 1800 when dismissed by President Adams.

Washington the Practical Christian

Taken from William Nell's Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812, the anecdote recounted below is descriptive of George Washington's attitude toward African-Americans.

Throughout the Revolutionary war Primus Hall was the steward of Col. Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts. He was free and communicative, and delighted to sit down with an interested listener and pour out those stores of absorbing and exciting anecdotes with which his memory was stored.

It is well known that there was no officer in the whole American army whose friendship was dearer to Washington, and whose counsel was more esteemed by him, than that of the honest and patriotic Col. Pickering. He was on intimate terms with him, and unbosomed himself to him with as little reserve as, perhaps, to any confident in the army. Whenever he was stationed within such a distance as to admit of it, he passed many hours with the Colonel, consulting him upon anticipated measures, and delighting in his reciprocated friendship.

Washington was, therefore, often brought into contact with the steward of Col. Pickering, the departed Primus. An opportunity was afforded to the negro to note him, under circumstances very different from those in which he is usually brought before the public, and which possess, therefore, a striking charm. I remember two of these anecdotes from the mouth of Primus. One of them is very slight, indeed, yet so peculiar as to be replete with interest. The authenticity of both may be fully relied upon.

Washington once came to Col. Pickering’s quarters, and found him absent.

“It is no matter,” said he to Primus. “I am greatly in need of exercise. You must help me to get some before your master returns.”

Under Washington’s directions the negro busied himself in some simple preparations. A stake was driven into the ground about breast high, a rope tied to it, and then Primus was desired to stand at some distance and hold it horizontally extended. The boys, the country over, are familiar with this plan of getting sport. With true boyish zest, Washington ran forwards and backwards for some time, jumping over the rope as he came and went, until he expressed himself satisfied with the “exercise.”

Repeatedly afterwards, when a favorable opportunity offered, he would say — “Come, Primus, I am in need of exercise;” whereat the negro would drive down the stake, and Washington would jump over the rope until he had exerted himself to his content.

On the second occasion, the great General was engaged in earnest consultation with Col. Pickering in his tent until after the night had fairly set in. Headquarters were at a considerable distance, and Washington signified his preference to staying with the Colonel overnight, provided he had a spare blanket and straw.

“Oh, yes,” said Primus, who was appealed to; “plenty of straw and blankets — plenty.”

Upon this assurance, Washington continued his conference with the Colonel until it was time to retire to rest. Two humble beds were spread, side by side, in the tent, and the officers laid themselves down, while Primus seemed to be busy with duties that required his attention before he himself could sleep. He worked, or appeared to work, until the breathing of the prostrate gentlemen satisfied him that they were sleeping; and then, seating himself on a box or stool, he leaned his head on his hands to obtain such repose as so inconvenient a position would allow. In the middle of the night Washington awoke. He looked about, and descried the negro as he sat. He gazed at him awhile, and then spoke.

“Primus!” said he, calling, “Primus!” Primus started up and rubbed his eyes. “What, General?” said he.

Washington rose up in his bed. “Primus,” said he, “what did you mean by saying that you had blankets and straw enough? Here you have given up your blanket and straw to me, that I may sleep comfortably, while you are obliged to sit through the night.”

“It’s nothing, General,” said Primus. "It’s nothing. I’m well enough. Don’t trouble yourself about me, General, but go to sleep again. No matter about me. I sleep very good.”

“But it is matter — it is matter,” said Washington, earnestly.

“I cannot do it, Primus. If either is to sit up, I will. But I think there is no need of either sitting up. The blanket is wide enough for two. Come and lie down here with me.”

“Oh, no, General!” said Primus, starting, and protesting against the proposition. “No; let me sit here. I’ll do very well on the stool.”

“I say, come and lie down here!” said Washington, authoritatively. “There is room for both, and I insist upon it!”

He threw open the blanket as he spoke, and moved to one side of the straw. Primus professes to have been exceedingly shocked at the idea, of lying under the same covering with the commander-in-chief, but his tone was so resolute and determined that he could not hesitate. He prepared himself, therefore, and laid himself down by Washington; and on the same straw, and under the same blanket, the General and the negro steward slept until morning.[1]

Conclusion: In Perspective

Of the nations that participated in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, America was the most resistant to the practice. Over a period of nearly 400 years, the United States received a small percentage of the African slaves sent around the world. An estimated 12,521,337 captives were taken from their native land of Africa over this period of time and became part of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. The percentage each nation acquired during the Trans-Atlantic trade is presented below:

United States 305,326 (2.4%)

Netherland 554,336 (4.4%)

Spain 1,061,524 (8.5%)

France 1,381,404 (11%)

Great Britain 3,259,441 (26%)

Portugal and Brazil 5,848,266 (nearly 47%)[2]

The biblical principles of the Reformation are the reason the practice of slavery was not observed to a greater extent in America. In a July fourth speech, President John Quincy Adams noted that the revelation of Scripture should be expected to exercise greater authority on the matter of slavery than the dictates of reason:

The inconsistency of the institution of domestic slavery with the principles of the Declaration of Independence, was seen and lamented by all the southern patriots of the Revolution…They universally considered it as a reproach fastened upon them by the unnatural step-mother country, and they saw that before the principles of the Declaration of Independence, slavery, in common with every other mode of oppression, was destined sooner or later to be banished from the earth. Such was the undoubting conviction of Jefferson to his dying day. In the Memoir of his Life, written at the age of seventy-seven, he gave to his countrymen the solemn and emphatic warning, that the day was not distant when they must hear and adopt the general emancipation of their slaves, “Nothing is more certainly written,” said he, “in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free.”[3] My countrymen! it is written in a better volume than the book of fate; it is written in the laws of Nature and [the laws] of Nature’s God.[4]

No, America was not founded upon the shoulders of racism. The historical evidence demonstrates that because of their biblical convictions, America's Founding Fathers were foremost in resisting this practice.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

Related Articles

Article Notes and Sources

[1] William C. Nell, Services of Colored Americans, in the Wars of 1776 and 1812i>, Second ed. (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1852), 39-40. These anecdotes first appeared in Godey's Lady's Book, June, 1849.

[2] "Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Estimates," Slave Voyages, September 30, 2020; https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates.

[3] Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew Adgate Lipscomb et al., 20 vols. (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903-1907), 1:72.

[4] John Quincy Adams, An Oration Delivered before the Inhabitants of the Town of Newburyport at Their Request on the Sixty-First Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1837 (Newburyport: Morse and Brewster, 1837), 50.