America’s Founding Fathers Were Not Deists

One of the tools employed by Marxists to undermine a nation is to discredit its heritage of founding fathers. In his book, Rules for Radicals,[1] communist advocate Saul Alinsky sows the seeds of class warfare—in part—by creating “disillusionment with past ways and values.”[2] Creating dissatisfaction with a nation’s history has been a tactic employed by Marxists around the world. The Marxist attack upon America’s “past ways and values” began more than a century prior to Black Lives Matter dismantling or defacement of historic sites in 2020.Founding Fathers Were Not Deists

From the beginning of America as an independent nation, forces have conspired (e.g., French Infidelity and the Illuminati[3] ) to deny America’s Christian origin, but none have enjoyed the degree of success as has been realized by the disciples of Karl Marx. The erosion of confidence in America’s religious foundation began in earnest with the rise of the “Great Agnostic,” Robert Ingersoll—son of Rev. John Ingersoll, one-time assistant to revivalist Charles G. Finney.[4] Building upon Ingersoll’s success, socialists and communists of every Marxian hue have aggressively and persistently attacked the Christian foundation of America since the beginning of the twentieth century.Founding Fathers Were Not Deists

Sadly, many Americans—including pastors—have bought into the myth that America’s Founding Fathers were Deists who believed in a God who created the world but who walked away from what He created. Deists argue that because God walked away from what He created, God could not have any relationship to the world. For this reason, Deists deny the divine inspiration of Scripture, the Virgin Birth, and the deity or Return of Jesus Christ; in short, Deists believe God exercises no “providential” or ongoing care of or interest in the world He has created.

Article Contents

Christianity in the Colonial Era

The English were late comers in the settlement of the New World, and though initial attempts of sustained settlements were unrealized, the First Virginia Charter (1605) did result in the first permanent English settlements that gave rise to America. In it, King James stated that part of his purpose in granting permission to settle in America was for the "propagating of [the] Christian Religion" and "the true Knowledge and Worship of God".[5]

The last English colony to be formed in America was Georgia (1732). From 1605 to 1732, charters that gave birth to America’s thirteen colonies were imbued with Christian influence. In addition to charters that granted right of settlement upon designated lands, documents governing the life of the colony emerged, among them were the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1639):

For as much as it hath pleased Almighty God by the wise disposition of his divine providence so to order and dispose of things that we the Inhabitants and Residents of Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield...knowing where a people are gathered together the word of God requires that to maintain the peace and union of such a people there should be an orderly and decent Government established according to God...to maintain and preserve the liberty and purity of the Gospel of our Lord Jesus which we now profess, as also, the discipline of the Churches, which according to the truth of the said Gospel is now practiced amongst us...[6]

Nowhere in the charters and colonial laws of the thirteen English colonies was a belief in an absent God ever promoted.

Christianity in the National Era

On May 15, 1776, the Continental Congress passed a resolve and preamble to encourage individual states to form their own governments. Two states decided to retain the documents that had governed their respective colonies—both of which were started by ministers (Connecticut and Rhode Island). Prior to the Continental Congress urging the colonies or states to form their own governments, two other states quickly formulated their first constitutions as they witnessed British government dissolving in America (New Hampshire and South Carolina).

If America's Founding Fathers were Deists, they could have disassociated themselves from the Christian ethos that characterized the charters of the colonial era which they were leaving. However, they did not. In a report submitted March 27, 1854, Congress’ Committee of the Judiciary noted the continuity of Christian influence between the colonial and national eras: “Had the people, during the Revolution, had a suspicion of any attempt to war against Christianity, that Revolution would have been strangled in its cradle.”[7]

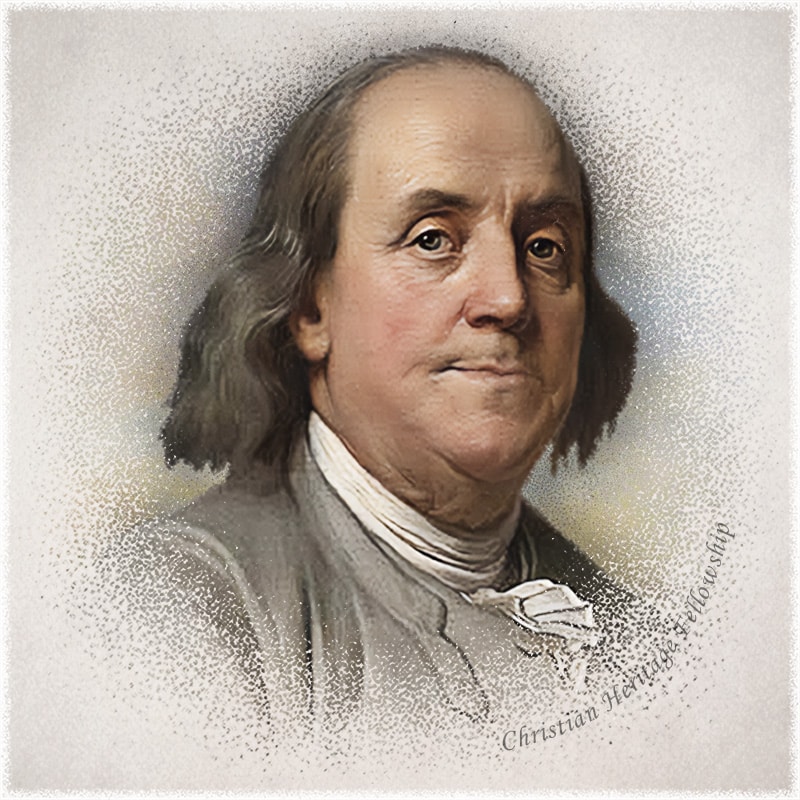

Nearly three months after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, on September 28, 1776, Pennsylvania ratified its first constitution, requiring members of the state assembly to affirm, “I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration.”[8] And who was the chairman of the state constitutional convention? None other than the purported arch Deist, “BENJ. FRANKLIN, Prest.”[9]

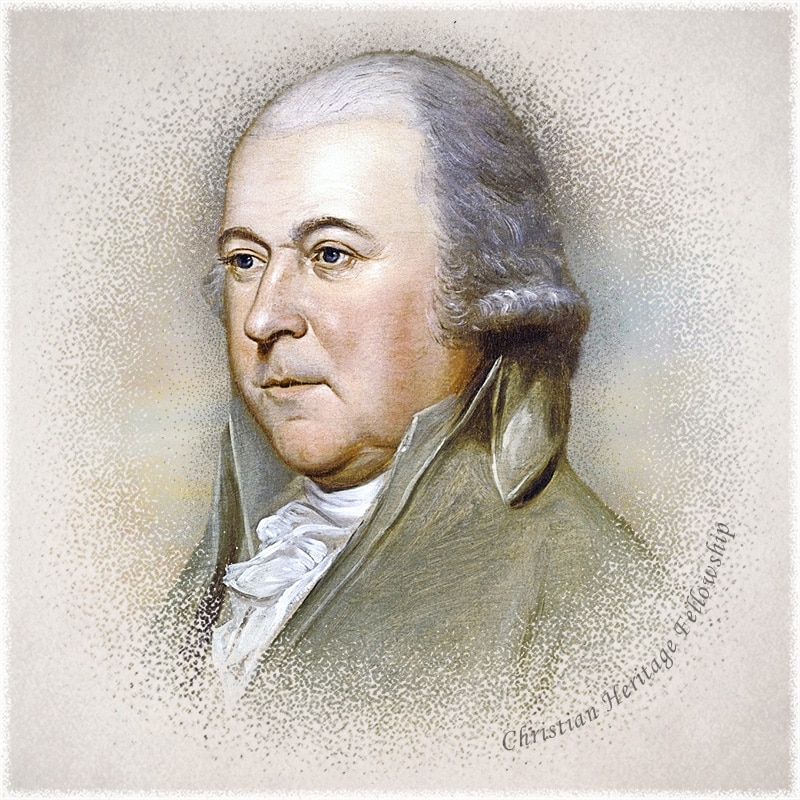

Massachusetts was the last of the states to compose a state constitution, completing this task on June 15, 1780. John Adams was the chief architect of the Massachusetts constitution and is frequently numbered by leftist historians with Franklin as an advocate of Deism, but his work on his state’s constitution would not suggest that. While other portions of the first Massachusetts constitution could be called upon to support the Christian influence in that document, Article III is most pertinent to the topic:

As the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depend upon piety, religion, and morality, and as these cannot be generally discussed through a community but by the institution of the public worship of God and of the public instructions in piety, religion, and morality: Therefore, To promote their happiness and to secure the good order and preservation of their government, the people of this commonwealth have a right to investtheir legislature with power to authorize and require, and the legislature shall, from time to time, authorize and require, the several towns, parishes, precincts, and other bodies-politic or religious societies to make suitable provision, at their own expense, for the institution of the public worship of God and for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality in all cases where such provision shall not be made voluntarily.[10]

So extensive was the influence of Christianity upon the rise of the United States as an independent nation that Congress’ Committee of the Judiciary observed in its report:

At the adoption of the Constitution, we believe every State—certainly ten of the thirteen—provided as regularly for the support of the Church as for the support of the Government: one, Virginia, had the system of tithes. Down to the Revolution, every colony did sustain [the Christian] religion in some form.[11]

More than four hundred pages of colonial charters and state constitutions witness to the place accorded to Christianity in the government of the first thirteen colonies and subsequent states—to say nothing of the role Christianity assumed upon additional legal standards of each.[12]

Sixteen Congressional Spiritual Proclamations

During the Second Continental Congress (May 10, 1775-February 28, 1781) and the Confederation Congress (March1, 1781-March 4, 1789), members of Congress issued sixteen spiritual proclamations, asking the states to fast, pray, and give thanks to God.[13]

After Congress approved each spiritual proclamation, they were sent to each state with the request that the citizens of the respective states would set that day aside from ordinary labor to engage in the spiritual exercise requested by the proclamation.

There is one word that completely decimates the argument that America’s Founding Fathers were not Christians but were Deists. That one word is “Providence,” and that word is everywhere in state papers as well as private personal papers. The Founders clearly meant to say that they believed God was not removed from the world He had created but was very active in it, guiding the events of world history. While the spiritual proclamations of Congress use the term extensively, the very first paragraph of the first proclamation demonstrates how important this theological concept was to the Founding Fathers:

As the great Governor of the World, by his supreme and universal Providence, not only conducts the course of nature[14] with unerring wisdom and rectitude, but frequently influences the minds of men to serve the wise and gracious purposes of his providential government; and it being, at all times, our indispensable duty devoutly to acknowledge his superintending providence,[15] especially in times of impending danger and public calamity, to reverence and adore his immutable justice as well as to implore his merciful interposition for our deliverance…[16]

The claims that America’s Founding Fathers were Deists cannot be supported anywhere by state papers—neither at the state nor federal levels. And this charge cannot be supported at the individual level either, as the following summary concerning the purported arch-Deists of the Founding Fathers demonstrates.

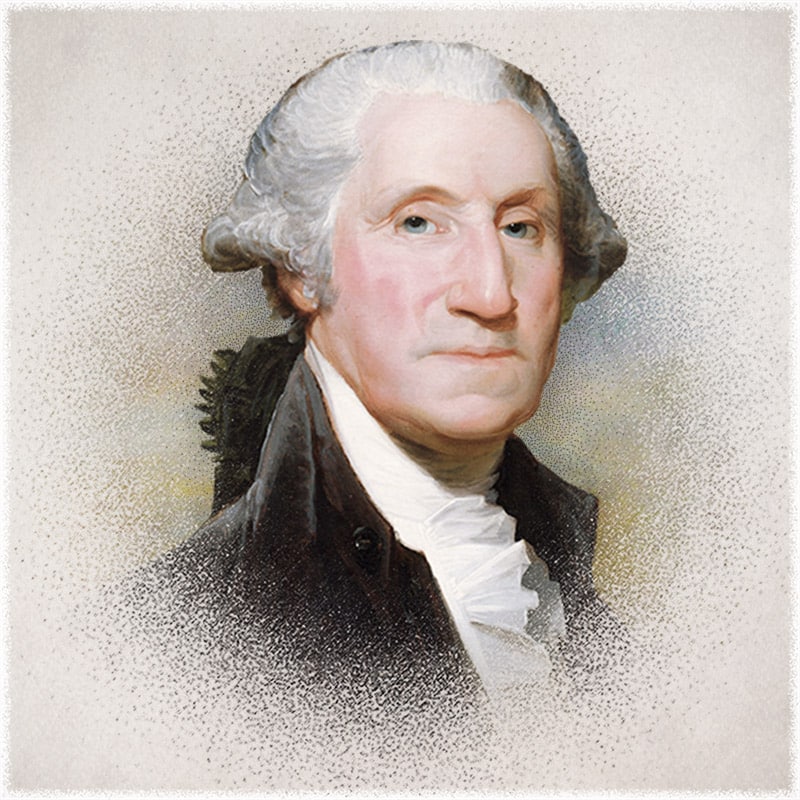

In his book, George Washington, The Image and the Man (1926), W. E. Woodward (one of the early America haters) attacked the character of America’s Founding Father. This fallacious biography has held currency only because Americans no longer know their history. Those who knew Mr. Washington best affirmed something far different than Woodward's fiction. Nelly Custis, Washington's daughter, affirmed, "I should have thought it the greatest heresy to doubt his firm belief in Christianity".[17]

Biographical evidence suggests George Washington was an advocate of Christianity, not only in public, but in his private life as well.[18] Many years after his death, an important spiritual habit of Washington was recounted and added to what was already known concerning his Christian devotional habits.From all indication, the account recorded below reflects a habit that characterized Mr. Washington's entire life—though it likely varied to some degree because of the circumstances of life.[19] In a letter written on January 10, 1859, Nathaniel Hewit recalled an experience that occurred nearly thirty years earlier that recounted Washington's faithful Christian devotional habits.

In the month of November 1829, I was in Fredericksburg, Va., and in the family of the Rev. Mr. Wilson, pastor of the Presbyterian church in that place. He occupied the house in which the mother of Washington lived and died. Mr. Wilson informed me that a nephew of Washington, Captain Lewis, who had been his clerk, and had the charge of his books and papers, and was daily in his library until his decease, related to him the following occurrence. It was the custom of Washington to retire to his library every evening precisely at nine o'clock, and, although he had visitors, he invariably left at that hour, and did not return. He remained alone in his library till ten o'clock and passed into his bedchamber by an inner door. Captain Lewis had long wondered how he spent that hour, knowing that he wrote nothing, and that the books and papers were as he himself left them the preceding day. During a violent storm of wind and rain, and when there were no visitors, he crept in his stocking-feet to the door, and through the keyhole he beheld him on his knees, with a large book open before him, which he had no doubt was a Bible—a large one being constantly in the room.[20]

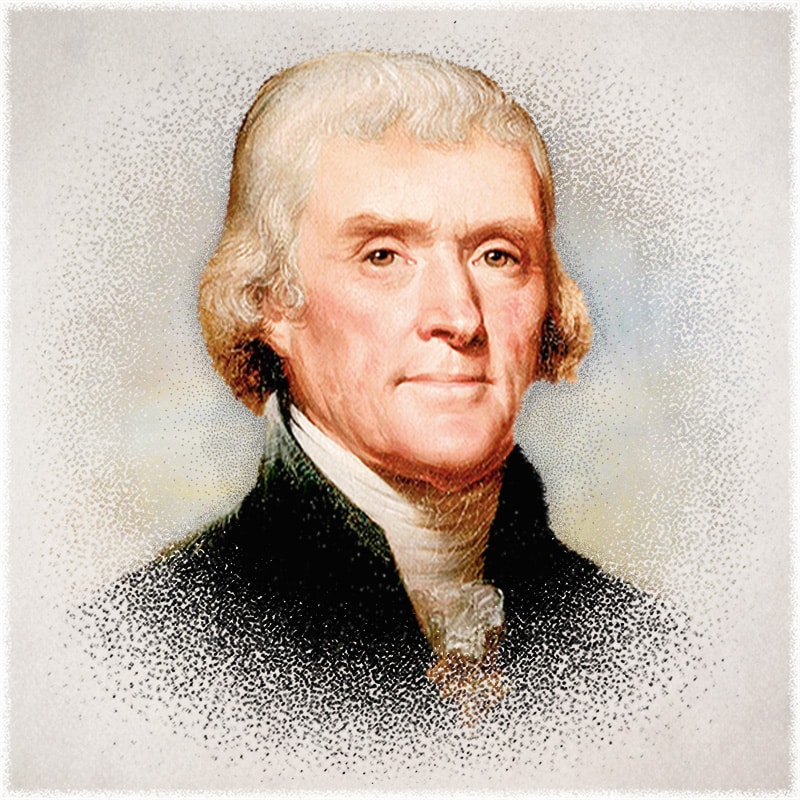

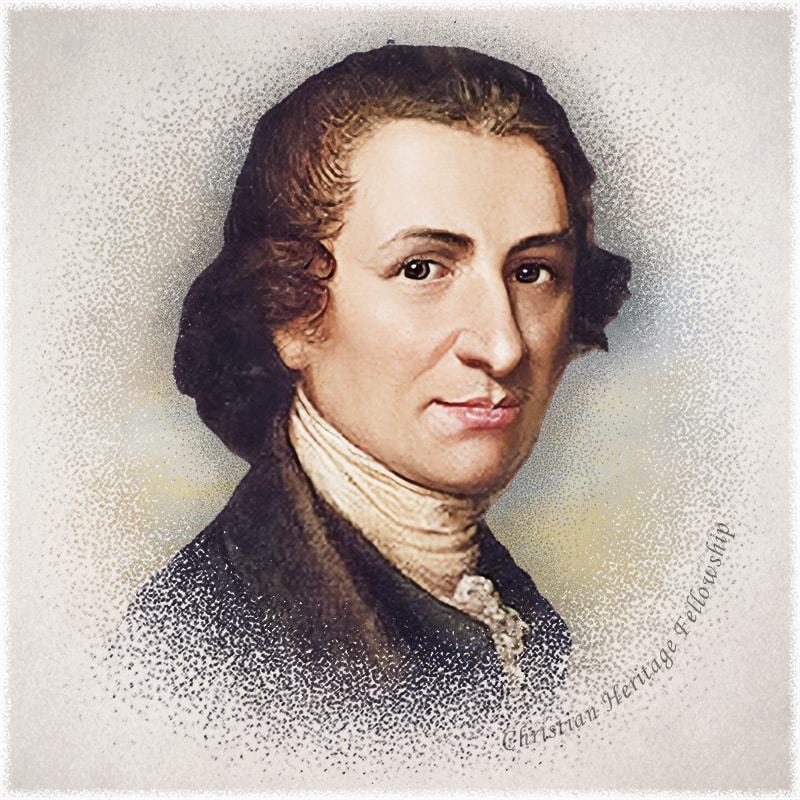

In 1998, the journal Science published an article that allegedly proved Thomas Jefferson had fathered at least one child through his slave Sally Hemings—an article that provided cover for President Bill Clinton who was then under impeachment proceedings for lying under oath concerning his own sexual exploits. But the article which exonerated Mr. Jefferson of fathering any children with Hemings gained far less public attention.[21] Nevertheless, this false charge has been used by Marxist sympathizers to vilify Jefferson, but Jefferson, though becoming unorthodox following the death of his wife, has related his sympathy concerning Christianity.

In a brief article titled, "Notes on Religion," written in October 1776, Thomas Jefferson summarized his views on the Christian faith. What was his view concerning the origin of the Bible? As he states, he believed "the [human] writers were inspired" by God, and for this reason, the Bible possessed authority concerning "the fundamentals of Xty [Christianity]"—and this only four months after penning the Declaration of Independence.[22]

A few months later, in February 1777, Mr. Jefferson assumed a leading role in planting a new church in Charlottesville. Subscriptions were raised first for a church called the “Protestant Episcopal Church,” but the name was subsequently changed to the “Calvinistical Reformed Church”. To the surprise of many, Mr. Jefferson is credited with having organized this congregation.[23]

Throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, secularists have contended that Jefferson attempted to write his own Bible, void of the miracles of the Bible, something that was characteristic of Deism. It is this work that secularists have designated as "Jefferson's Bible." The fact is, he took two Bibles he had in the White House, cut from them the words of Jesus (which are commonly regarded as the "red letters" ) and arranged them on separate sheets of paper.[24] His title indicates his intent: "…an abridgment of the New Testament for the use of the Indians."[25] As has been repeatedly demonstrated by Jefferson scholars,[26] this abridgment did indeed include miracles, and miracles were rejected by true Deists.

While president, Mr. Jefferson attended the church in the Capitol building,[27] and on one occasion was questioned concerning his attendance there. He responded saying,

No nation has ever yet existed or been governed without religion nor can be. The Christian religion is the best religion that has been given to man and I, as Chief Magistrate of this nation, am bound to give it the sanction of my example.[28]

One final observation concerning Mr. Jefferson is appropriate. While it is not accurate to suggest he was an orthodox Christian, his own claim gives no credibility to the notion he was a Deist. In a letter dated January 9, 1816, sent to the former Secretary of the Continental Congress, Charles Thomson, Jefferson made a bold claim to be a follower of Christ:

I, too, have made a wee-little book from the same materials, which I call the Philosophy of Jesus; it is a paradigm of His doctrines, made by cutting the texts out of the book, and arranging them on the pages of a blank book, in a certain order of time or subject. A more beautiful or precious morsel of ethics I have never seen; it is a document in proof that I am a real Christian, that is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus, very different from the Platonists, who call me infidel and themselves Christians and preachers of the gospel…[29]

Having come under the spell of Deism in his youth, Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography, "I soon became a thorough Deist." But he soon realized the difficulties of living according to the moral standards of Deism: "...which at times gave me great trouble, I began to suspect that this doctrine...was not very useful."[30] Looking back upon his gullible youth in his autobiography, he realized, "the kind hand of Providence, or some guardian angel, or accidental favorable circumstances and situations, or all together, preserved me, through this dangerous time of youth" .[31]

Mr. Franklin, alleged to be the arch-Deist of the Founders, himself refutes the myth that the Founding Fathers were a group or radical Deists. When in France, Franklin composed a description of what Frenchmen who proposed to move to America would find there:

. . . bad examples to youth are more rare in America, which must be a comfortable consideration to parents. To this may be truly added, that serious religion, under its various denominations, is not only tolerated, but respected and practiced. Atheism is unknown there; infidelity [Deism] rare and secret; so that persons may live to a great age in that country, without having their piety [Christian scruples] shocked by meeting with either an atheist or an infidel. And the Divine Being seems to have manifested his approbation of the mutual forbearance and kindness with which the different Sects [Christian denominations] treat each other, by the remarkable prosperity with which He has been pleased to favor the whole country.[32]

Time and space do not afford further discussion of Mr. Franklin’s call to prayer at the Constitutional Convention (June 28, 1787),[33] but a footnote found in the journal of Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury speaks volumes concerning the way he died.

Robert Grace was the general manager of both Coventry Forge and Warwick Furnace, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Ben Franklin visited his friend regularly and gave him the plans for his “Pennsylvania Fireplace,” the first enclosed stove. It is believed the stove was tested in the southwest parlor of the Grace home, the Coventry House—the room where Methodist meetings were held, and it was to Robert Grace's widow, Rebecca, to whom Mr. Franklin appealed on his death bed:

Mrs. Rebecca Grace, twice widowed…had been a disciple of [revivalist George] Whitefield but rejected his Calvinism after reading Wesley’s sermon on Free Grace [perhaps through Franklin] …Benjamin Franklin wanted to marry her, but she rejected him because of his religious views; he sent for her when he lay dying, and she pointed him to religion [in Christ] .[34]

In discussions concerning this topic, the name of Thomas Paine is inevitably evoked as alleged evidence of the general disposition of all Founding Fathers toward Deism. Paine exercised considerable influence early in the War of Independence through his two works of Common Sense (1776)[35] and American Crisis (1776-1783),36 but his latter two works upon which his Deism is asserted—Rights of Man (1791-1792)37 and Age of Reason (1794, 1795, and 1807)38—were nothing like his first two works. Nowhere in the first two works, so highly prized by American Founding Fathers, does Paine attack Christianity but rather employs the Bible in defense of his arguments. Paine left America, became embroiled in the French Revolution, and imbued with Voltaire’s infidelity before returning to America.

Seeking the advice of Benjamin Franklin prior to publishing his Age of Reason, it is believed Mr. Franklin in a letter warned Paine not to publish his newly acquired anti-Christian sentiments: “I have read your manuscript with some attention….I would advise you, therefore, not to attempt unchaining the tiger, but to burn this piece before it is seen by any other person…If men are so wicked with religion, what would they be if without it.”[39] Characteristic of the response of other Founding Fathers to Paine’s defection to infidelity, John Adams wrote: “The Christian religion is, above all the religions that ever prevailed or existed in ancient or modern times, the religion of wisdom, virtue, equity and humanity, let the Blackguard Paine say what he will.”[40]

From the First Charter of Virginia in 1605 through the Constitution, America has been built upon a belief that compliance with “the laws of nature and nature’s God” would produce “a more perfect union.” Despite personal foibles, America’s Founding Fathers were remarkable and courageous individuals!

In contrast, in every nation where Marxism and its socialistic and communistic disciples have placed their feet, promises of equality and justice have always ended in the enslavement of those nations. Always! Despite their claims, socialism and communism have never produced a happier and freer people.

The kind of society that Saul Alinsky and his Marxist friends would visit upon the world can be anticipated in his book’s dedication to the world’s “first radical”:

Lest we forget at least an over-the-shoulder acknowledgement to the very first radical: from all our legends, mythology, and history (and who is to know where mythology leaves off and history begins—or which is which), the first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom—Lucifer.[41]

And, into the kingdom of Lucifer is where all Marxists, socialists, and communists lead those gullible enough to follow.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Saul D. Alinsky, Rules for Radicals; a Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals (New York: Random House, 1971).

[2] Saul D. Alinsky, Rules for Radicals; a Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals, Vintage Books ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), xxii.

[3] See, Timothy Dwight, The Duty of Americans at the Present Crisis, Illustrated in a Discourse, Preached on the Fourth of July, 1798 (New Haven, CT: Thomas and Samuel Green, 1798), 10-14.

[4] Rufus Rockwell Wilson, "“Bob” Ingersoll: A Sketch of the Life of America's Most Noted Agnostic," The Elmira Telegram, Sunday, March 16, 1890, https://www.crookedlakereview.com/articles/34_66/41aug1991/41wilson.html.

[5] See, The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the State, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America, ed. Francis Newton Thorpe, 7 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), 7:3783-89.

[6] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 1:519.

[7]Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives Made During the First Session of the Thirty-Third Congress, by James Meacham, 124, Vol. 2 (Washington: A. O. P. Nicholson, 1854), 6.

[8] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 5:3085.

[9] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 5:3092.

[10] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 3:1889-90.

[11] Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives Made During the First Session of the Thirty-Third Congress, 6.

[12] Stephen Allen Flick, Early Charters and Constitutions of the First Thirteen American States (Christian Heritage Fellowship, 2022).

[13] The sixteen spiritual proclamations of the Second Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress are as follows:

Second Continental Congress(May 10, 1775-February 28, 1781)

#1 – June 1775: Day of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer

#2 – March 1776: Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer

#3 – December 1776: Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer

#4 – November 1777: Day of Thanksgiving

#5 – March 1778: Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer

#6 – November 1778: Day of Thanksgiving

#7 – March 1779: Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer

#8 – October 1779: Day of General Thanksgiving

#9 – March 1780: Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer

#10 – October 1780: Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer

Confederation Congress(March1, 1781-March 4, 1789)

#11 – March 1781: Day of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer

#12 – October 1781: Day of Public Thanksgiving and British Surrender

#13 – March 1782: Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer

#14 – October 1782: Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer

#15 – October 1783: Day of Thanksgiving

#16 – August 1784: Day of Solemn Prayer and Thanksgiving

[14] Emphasis added.

[15] Emphasis added. Congress makes it clear that irreligion or secularism was intolerable to human government. Delegates believed it was the duty of human government to acknowledge divine government.

[16] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 2:87.

[17] Jared Sparks, The Writings of George Washington; Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original Manuscripts; with a Life of the Author, Notes, and Illustrations, 12 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1858), 12:406.

[18] See my book, Stephen A. Flick, America’s Founding Fathers and the Bible: A Select Study of America’s Christian Origin (Clinton, Tennessee: Christian Heritage Press, 2018), 30-44.

[19] One of the most widely circulated biographies of George Washington was a small volume published by the American Sunday School Union. This work recounted what was reported concerning the prayer or devotional life of Washington in the war years by a variety of sources. Anna C. Reed, Life of Washington (n.p.: American Sunday-School Union, 1824; reprint, Green Forest: AR, Attic Books, 2010), 117-19.

[20] Morris, Civil Institutions of the United States, 501-502.

[21] See, David Barton, The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You've Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012), 1-30.

[22] Emphasis added. Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford, 12 vols. (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1904), 2:254-55.

[23] Mark A. Beliles and Jerry Newcombe, Doubting Thomas? The Religious Life and Legacy of Thomas Jefferson (New York: MJ, 2015), 22.

[24] Barton, The Jefferson Lies, 72.

[25] Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1888), 3:654.

[26] See Dickinson W. Adams and Ruth W. Lester, Jefferson's Extracts from the Gospels (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983); Charles B. Sanford, The Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995); Sanford, Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson; Mark Beliles, Thomas Jefferson’s Abridgement of the Words of Jesus of Nazareth (Charlottesville: Mark Beliles, 1993).

[27] See, Stephen A. Flick, When the United States Capitol Was a Church (Clinton, TN: Christian Heritage Press, 2016).

[28] James H. Hutson and Jay I. Kislak, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1998), 96.

[29] Emphasis added. Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew Adgate Lipscomb et al., 20 vols. (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903-1907), 14:385.

[30] Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin with Notes and a Sketch of Franklin's Life from the Point Where the Autobiography Ends, Drawn Chiefly from His Letters (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888), 77-78.

[31] Franklin, Autobiography, 79.

[32] "Benjamin Franklin, Information to Those Who Would Remove to America," The Founders' Constitution (http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch15s27.html, April 17, 2015).

[33] James Madison, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 3 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), 1:450-52.

[34] Francis Asbury, Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, 3 vols. (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1958), 1:187.

[35] Thomas Paine, Common Sense: Addressed to the Inhabitants of America, on the Following Interesting Subjects: I. Of the Origin and Design of Government in General, with Concise Remarks on the English Constitution. II. Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession. III. Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs. Iv. Of the Present Ability of America, with Some Miscellaneous Reflections, A new ed. (Philadelphia: Printed and sold by W. and T. Bradford, 1776).

[36] Thomas Paine, American Crisis. Number I (Norwich [CT] J. Trumbull, [1776] ).

[37] Thomas Paine, Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution (London: J. Johnson, 1791-1792).

[38] It was published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807. Thomas Paine, Age of Reason: Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology, vol. 1, 3 vols. (Paris: Borris, 1794).

[39] Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin: Containing Several Political and Historical Tracts Not Included in Any Former Edition and Many Letters Official and Private, Not Hitherto Published: With Notes and a Life of the Author, ed. Jared Sparks, 10 vols. (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company, 1836-1840), 10:281-82.

[40] John Adams and L. H. Butterfield,Diary and Autobiography, 4 vols. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1961), 3:233-34, July 26, 1796.

[41] Alinsky, Rules for Radicals, ix.