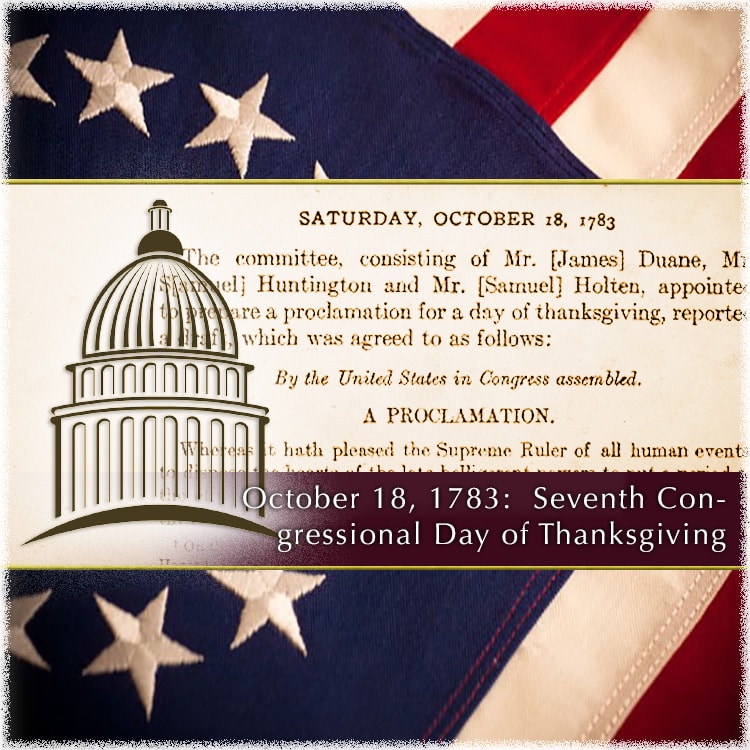

From June 1775 to August 1784, the Continental Congress issued sixteen spiritual proclamations, calling all Thirteen States to fast, pray, and give thanks to God. During this period of time, Congress most commonly issued proclamations in the spring calling upon the states to fast and pray. And, in the fall of the year, Congress issued proclamations of thanksgiving. This alternating pattern was first observed in the New England colonies and later was brought into the Southern colonies. In Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and several other members of the Virginia House of Burgesses advocated for these observances.[1] Seventh Congressional Day of Thanksgiving

Tragically, contemporary attempts to recount the history of America often completely ignore the formative influence the Christian faith exercised upon America's founding. But as will be seen in the congressional spiritual proclamation of October 1783, America's Founding Fathers had no intention of denying the Christian faith a role in the life of the nation.

The subject addressed in this article is discussed at greater length in When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God. Christian Heritage Fellowship would be honored to work with individuals, businesses, churches, institutions, or organizations to help communicate the truth concerning the positive influence of the Christian faith by providing bulk pricing: Please contact us here... To purchase a limited quantity of this publication, please click: Purchase here...

Article Contents

Following the enactment of the Articles of Confederation in 1781, the Presidents of Congress began to hold office—as stipulated by the Articles—for a term of one year, though this was not always applied precisely. John Hanson from Maryland, the ninth President of Congress, was the first to begin to observe this stipulation on the Articles of Congress.

The tenth President of Congress was Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, who served from November 4, 1782 to November 3, 1783. Boudinot was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on May 2, 1740 to Elias Boudinot III, a merchant and silversmith and was both neighbor and friend of Benjamin Franklin. Like many in early America, Elias was home-schooled before being sent to Princeton where he studied law. Princeton (which was known as the College of New Jersey at that time) became one of the most influential centers for the sake of American Independence under the presidency of Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon, who was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and an instrumental figure in the effort to convene the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Though Elias Boudinot graduated from Princeton before the presidency of Dr. Witherspoon, there can be no doubt that the two men knew each other well given the fact that Elias became a member of the board of trustees of Princeton in 1772 and retained his membership on the board until his death in 1821. While at Princeton, Elias began to read the law as a legal apprentice to Richard Stockton—a signer of the Declaration of Independence—and who had graduated from Princeton in 1748 and who would subsequently become Elias's brother-in-law.

Elected to Congress beginning on July 7, 1778, his term concluded at the end of the year; he did not return to Congress until 1781, at which time he served in this office until 1783 when the term expired.

When American independence was won, Elias returned to his law practice, but, like George Washington, he was called once again to serve his country. Once the United States Constitution was ratified in 1789, he was elected from New Jersey to the United States House of Representatives to serve in the First, Second, and Third Congresses (from March 4, 1789 to March 3, 1795), but refused to be re-nominated for the Fourth Congress. The same year he stepped down from Congress, President Washington nominated him as the second Director of the Mint, in which capacity he served from 1795 to 1805.

One of Boudinot's legacies to America occurred during his first term in the House of Representatives. On Friday September 25, 1789, Mr. Boudinot made a motion on the floor of the House of Representatives that would eventually help establish America's annual Thanksgiving, drawing upon the fact that the Continental and Confederation Congresses exercised this same practice—of which he had been a participant as President of Congress.

As a Presbyterian, Boudinot's deeply held biblical convictions expressed themselves throughout his life, but two expressions of his mature Christian faith are particularly noteworthy. The first expression concerned his refutation of the champion of present-day American secularists, Thomas Paine. Whereas Paine's first significant political work, Common Sense, employed arguments based upon the Bible, his subsequent works The Rights of Man and Age of Reason were decidedly secular and irreligious. In fact, after receiving a manuscript of Age of Reason from Paine before its publication, Benjamin Franklin pleaded with Paine not to publish it. With other Founding Fathers, Boudinot was incensed by Paine's Age of Reason and openly challenged Paine by publishing his own response in 1801 titled, The Age of Revelation, or The Age of Reason Shown to Be an Age of Infidelity. In his book, Boudinot not only demonstrated his contempt for Paine's irreligion but also discloses the contempt that America's Founding Fathers had for secular infidelity and deism. Boudinot's book demonstrates how well versed in Christian theology most of America's Founding Fathers truly were.

The second notable expression of Boudinot's Christian faith in his most mature years occurred in relation to the formation of the American Bible Society. In poor health, Elias Boudinot was burdened for a "general Bible society" that could distribute the Bible throughout America and around the world, and on May 11, 1816, he was elected the first president of the American Bible Society. Beginning with Elias Boudinot, some very distinguished Americans have occupied the presidency of the American Bible Society. From the beginning of the American Bible Society, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Jay, was a member. At the beginning of the Society, Chief Justice Jay was elected vice-president, and at the death of Elias Boudinot in 1821, Jay was elected president of the society.[2]

When British General Charles Cornwallis surrendered his troops to George Washington following the Siege of Yorktown, American hopes for peace began to arise in earnest. Despite continuing skirmishes, peace talks began in Paris in April 1782 between American and British negotiators. These negotiations continued through the summer with Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams, representing the United States. Henry Laurens joined the American effort in Paris the following year. A year after talks began, negotiations had developed sufficiently that Congress was asked to give its approval to the committee's work, and Elias Boudinot, as President of Congress, signed the Preliminary Articles of Peace on April 15, 1783.[3] Not until January 14, 1784 was Congress able to approve the final form of the Treaty of Paris.

One tragic personal observation should enable readers to understand the sacrifice that was made by America's Founding Fathers. As noted in the discussion of the congressional spiritual proclamation of October 1782, Lieutenant-colonel John Laurens was killed on August 27, 1782 in the Battle of Combahee River following the British surrender at Yorktown. After his son was killed, Henry Laurens joined the peace negotiations in Paris and was particularly helpful in achieving their intended goal.

Committee Composes Proclamation

As was the case with the two previous proclamations, the Journals of Congress do not indicate when a committee was selected to write this proclamation, but it is evident that a three-man committee was selected. Special attention is drawn to the fact in this proclamation that, "in the course of the present year, hostilities have ceased." While America would have to wait several more months—until January 1784—before Congress could ratify the final form of the Treaty of Paris, the proclamation committee and Congress as a whole were confident that their Revolution was at an end. This proclamation resounds with praise for the victory the "Supreme Ruler of all human events" has brought to their nation:

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 18, 1783

The committee, consisting of Mr. [James] Duane, Mr. S[amuel] Huntington and Mr. [Samuel] Holten, appointed to prepare a proclamation for a day of thanksgiving, reported a draft, which was agreed to as follows:

By the United States in Congress assembled.

A PROCLAMATION

Whereas it hath pleased the Supreme Ruler of all human events, to dispose the hearts of the late belligerent powers to put a period to the effusion of human blood, by proclaiming a cessation of all hostilities by sea and land, and these United States are not only happily rescued from the dangers and calamities to which they have been so long exposed, but their freedom, sovereignty and independence ultimately acknowledged. And whereas in the progress of a contest on which the most essential rights of human nature depended, the interposition of Divine Providence in our favor hath been most abundantly and most graciously manifested, and the citizens of these United States have every reason for praise and gratitude to the God of their salvation. Impressed, therefore, with an exalted sense of the blessings by which we are surrounded, and of our entire dependence on that Almighty Being, from whose goodness and bounty they are derived, the United States in Congress assembled do recommend it to the several States, to set apart the second Thursday in December next, as a day of public thanksgiving, that all the people may then assemble to celebrate with grateful hearts and united voices, the praises of their Supreme and all bountiful Benefactor, for his numberless favors and mercies. That he hath been pleased to conduct us in safety through all the perils and vicissitudes of the war; that he hath given us unanimity and resolution to adhere to our just rights; that he hath raised up a powerful ally to assist us in supporting them, and hath so far crowned our united efforts with success, that in the course of the present year, hostilities have ceased, and we are left in the undisputed possession of our liberties and independence, and of the fruits of our own land, and in the free participation of the treasures of the sea; that he hath prospered the labor of our husbandmen with plentiful harvests; and above all, that he hath been pleased to continue to us the light of the blessed gospel, and secured to us in the fullest extent the rights of conscience in faith and worship. And while our hearts overflow with gratitude, and our lips set forth the praises of our great Creator, that we also offer up fervent supplications, that it may please him to pardon all our offences, to give wisdom and unanimity to our public councils, to cement all our citizens in the bonds of affection, and to inspire them with an earnest regard for the national honor and interest, to enable them to improve the days of prosperity by every good work, and to be lovers of peace and tranquility; that he may be pleased to bless us in our husbandry, our commerce and navigation; to smile upon our seminaries and means of education, to cause pure religion and virtue to flourish, to give peace to all nations, and to fill the world with his glory.

Done by the United States in Congress assembled, witness his Excellency Elias Boudinot, our President, this 18th day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty-three, and of the sovereignty and independence of the United States of America the eighth.[4]

Contemporary historians have commonly vilified most of America's Founding Fathers; often they have painted their characters in dark hues or have simply neglected to inform their audiences of pivotal information that would soften or eliminate such historians' preconceived secular opinions. Characteristic of this style of writing is Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies: The Patriots, written by David Fisher and Bill O'Reilly.[5] Such contemporary "histories" of America completely obscure the formative influence of the Christian faith upon the lives of the Founding Fathers and their labor to craft a new nation. For those willing to exert the effort necessary to discover the truth concerning America's founding, they will find the congressional record—among many other sources—replete with the influence Christianity exercised upon the Founding Fathers.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Derek Davis, Religion and the Continental Congress, 1774-1789: Contributions to Original Intent (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 84.

[2] For a scholarly history of the American Bible Society, please see John Fea, The Bible Cause: A History of the American Bible Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[3] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 24:241-252.

[4] Journals of the Continental Congress, 25:699-701.

[5] David Fisher and Bill O'Reilly, Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies: The Patriots (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2016).