- 16

- 16shares

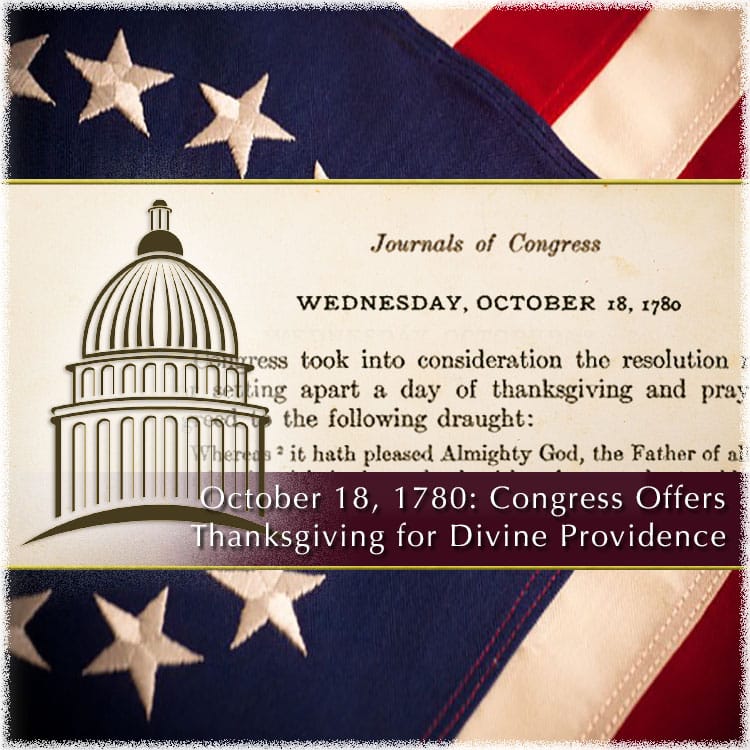

At the end of 1780, the endurance of American revolutionary forces had been severely tested by British military might. So dire was the situation that General George Washington pled for assistance from the Continental Congress. Undaunted by the looming prospect of defeat, Congress—following a pattern of fasting, prayer, and thanksgiving—once again called upon the states to establish a day of thanksgiving to be observed by their citizens. That year Congress asked the states to recognize December 7, 1780 as a day of thanksgiving for God's providential care.Congress Offers Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

The subject addressed in this article is discussed at greater length in When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God. Christian Heritage Fellowship would be honored to work with individuals, businesses, churches, institutions, or organizations to help communicate the truth concerning the positive influence of the Christian faith by providing bulk pricing: Please contact us here... To purchase a limited quantity of this publication, please click: Purchase here...

Article Contents

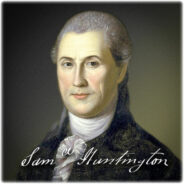

President of Congress—Son-in-Law of Pastor

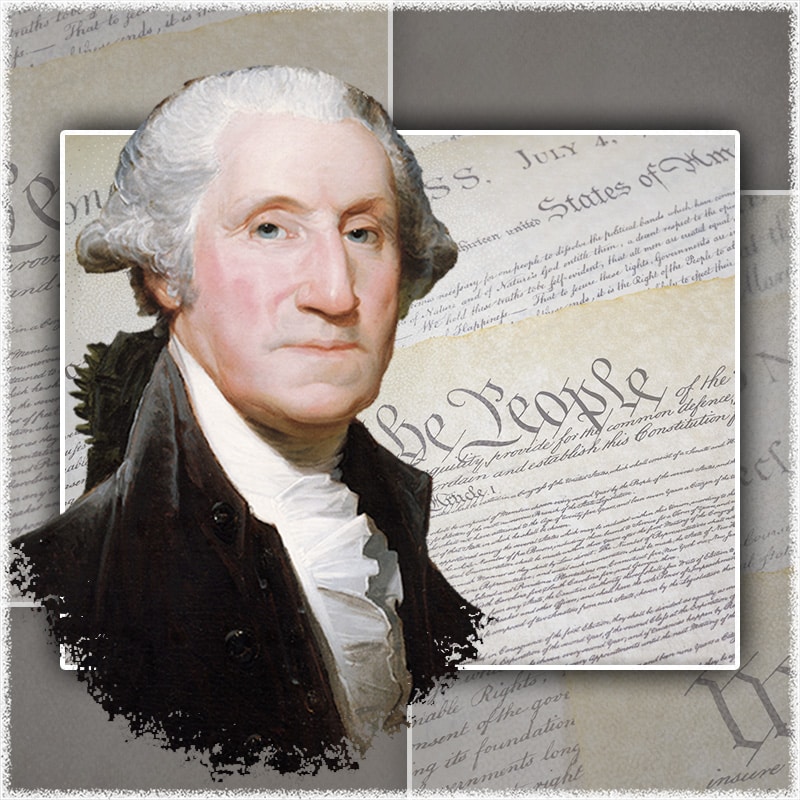

In the fall of 1780, Samuel Huntington of Connecticut was president of the Continental Congress when delegates proclaimed a "day of thanksgiving and prayer." For Congress, this was the tenth spiritual proclamation issued since 1775, and the third of four proclamations issued under the presidency of Samuel Huntington, who presided over Congress from September 28, 1779 to July 9, 1781.

As noted in the discussion of the previous proclamation, Samuel was the son-in-law of well-known Congregational minister, Ebenezer Devotion. What is not well-known, however, is the role clergy played in the American Revolution. In fact, King George III regarded the American Revolution as a black-robe rebellion, implying that pastors—who often wore black clerical robes—were responsible for inciting the Revolution. And, Samuel Huntington's father-in-law, as a Congregational minister, was a member of the Calvinistic theological tradition. In America and elsewhere throughout Europe, this theological tradition provided much of the theology necessary to set America on a course toward a form of republican government. In addition to the four proclamations adopted while he was President of Congress, Huntington participated in two of the committees charged with drafting spiritual proclamations.

An understanding of two important events help clarify Congress' proclamation of October, 1780. The first of these two events is very prominent early in the proclamation. It concerns the betrayal of the American cause of independence by Benedict Arnold.

Born in Norwich, Connecticut to a family of educators and social standing, Benedict Arnold early rejected his Christian upbringing. As one biographer noted, "Arnold's training was under the influence of the strictest kind of New England religious thought, against which he displayed a distinct spirit of revolt."[1] And, when war between the Colonies and Great Britain erupted, it was not long before Arnold revolted politically.

Together with Ethan Allen, Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775, less than a month after the outbreak of military conflict between the Colonies and Great Britain at the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. As early as November, 1776, Arnold became embittered when Congress promoted five brigadier-generals to major-generals, all of whom had been subordinates to him. Later promoted to major-general, he again distinguished himself at the two Battles of Saratoga in 1777, but his treachery and betrayal of his country did not wait long after his battlefield heroism.

By the summer of 1779, Arnold was conveying information of the greatest importance concerning American resources and movement to the British. Unaware of Arnold's treachery, General Washington assigned him to the command of the key post at West Point. On September 21, 1780, Arnold met with British Major John Andre and arranged details for the surrender of West Point. While attempting to return to his lines, Major Andre was captured on the morning of September 23. Papers detailing Arnold's activity were found on Andre and sent to General Washington, who was in route to West Point for an inspection. Receiving word of Andre's arrest, Arnold fled to the British ship, the Vulture, leaving Andre to the fate of his execution on October 2, 1780. Two months later, Arnold was sent by the British commander on a ruthless marauding expedition against his former countrymen in Virginia—only the first of such guerrilla efforts. In Virginia, Governor Thomas Jefferson offered a 5,000 guineas reward for his capture. In December 1781, Arnold and his family sailed for England.

The Journals of Congress for October 13, 1780 record the names of the three members chosen to draft a spiritual proclamation. The delegates selected to serve on the committee included Samuel Adams, William Churchill Houston and Rev. Frederick Muhlenberg. Arnold's treachery was particularly noted by Congress in its October prayer and thanksgiving proclamation. But, a second issue was also of concern—and for good reason.

During the first three years of the American Revolution, the most extensive military campaigns were waged in the northern states. But after the failure of the British Saratoga Campaign (from June 14 – October 17, 1777), British commanders turned their efforts to a "southern strategy," which commenced late in 1778. As noted previously in the discussion of spiritual proclamation number four, the loss of the British at Saratoga was an important turning point in the Revolution. By the end of 1780, the British could boast of significant gains against the American army. Savannah, Georgia had fallen early to the British "southern strategy," and by the end of 1780, two American armies had been defeated at Charleston and Camden, South Carolina. Though General Washington had struggled with the lack of discipline associated with a militia, the end of 1780 brought a level of desperation to Congress and the American military forces which they had not previously known.

Five days after the selection of the congressional committee to compose the prayer and thanksgiving proclamation, General Washington penned a circular letter and sent it to each of the states explaining the dire circumstances of the American army. The years of war had depleted American resources, and the ability to raise and equip an army was meeting with nearly insurmountable opposition. In the opening paragraph of his letter, Washington wasted no time in cutting to the quick of the subject:

In obedience to the orders of Congress, I have the honor to transmit you the present state of the troops of your line, by which you will perceive how few men you will have left after the first of January next. When I inform you also, that the regiments of the other lines will be in general as much reduced as yours, you will be able to judge how exceedingly weak the army will be at that period, and how essential it is the States should make the most vigorous exertions to replace the discharged men as early as possible.[2]

In his lengthy letter, he rehearsed the history of the war and the fact that America was greatly handicapped by a lack of a standing professional army and was forced to rely on poorly trained militia who often fled the battlefield or gave a poor account of themselves against their British foe. In the Battle of Camden, "The militia fled at the first fire, and left the continental troops surrounded on every side and overpowered by numbers, to combat for safety instead of victory."[3] Under such conditions, morale suffered not only among frontline soldiers, but also extended to Washington's officers. From January to October of 1780, one hundred sixty officers resigned their commissions and dismal circumstances—as noted by Washington—only promised to make matters worse:

Our officers are in general indecently defective in clothing—our men are almost naked, totally unprepared for the inclemency of the approaching season. We have no magazines for the winter—the mode of procuring our supplies is precarious, and all the reports of the officers employed in collecting them are gloomy.[4]

Further, citizens sympathetic to the cause of independence had borne the heavy burden of supplying the needs of the army, and the reservoir of goodwill necessary to continue the war was quickly being depleted. Results for their investments were few, and the growing debt made it all that more difficult to secure both soldiers and the supplies necessary to keep them on the battlefield. With the American army in such a haggard state, General Washington made his impassioned plea to the states for their continued support of the cause of independence.

The same day that General Washington penned his circular letter to the states (Wednesday, October 18, 1780), Congress formally accepted the report from the committee charged with composing the October prayer and thanksgiving proclamation. Two days earlier (on Monday, October 16) it had been submitted, but the Journals of Congress failed to record a formal vote on the matter. On the eighteenth, the vote was taken and the proclamation was recorded in the Journals.[5]

Committee Composes Proclamation

Both the appointment of the committee and the final form of the proclamation adopted by Congress are presented below. What candid reader of these excerpts from the Journals of Congress will conclude that America's Founding Fathers sought to establish as secular form of government?

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 13, 1780

Resolved, That a committee of three be appointed to draught a proclamation for setting apart a day of thanksgiving and prayer.

The members chosen, Mr. [Samuel] Adams, Mr. [William Churchill] Houston and Mr. [Frederick A.] Muhlenberg.[6]

In less than a week after the committee was charged to draft a proclamation, Congress adopted a final form:

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 18, 1780

Congress took into consideration the resolution reported for setting apart a day of thanksgiving and prayer, and agreed to the following draught:

Whereas, it hath pleased Almighty God, the Father of all mercies, amidst the vicissitudes and calamities of war, to bestow blessings on the people of these states, which call for their devout and thankful acknowledgments, more especially in the late remarkable interposition of his watchful providence, in rescuing the person of our Commander in Chief and the army from imminent dangers, at the moment when treason was ripened for execution; in prospering the labors of the husbandmen, and causing the earth to yield its increase in plentiful harvests; and, above all, in continuing to us the enjoyment of the gospel of peace;

It is therefore recommended to the several states to set apart Thursday, the seventh day [of December next, to be observed as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer; that all the people may assemble on that day to celebrate the praises of our Divine Benefactor; to confess our unworthiness of the least of his favors, and to offer our fervent supplications to the God of all grace; that it may please him to pardon our heinous transgressions and incline our hearts for the future to keep all his laws; to comfort and relieve our brethren who are any wise afflicted or distressed; to smile upon our husbandry and trade; to direct our public councils, and lead our forces, by land and sea, to victory; to take our illustrious ally under his special protection, and favor our joint councils and exertions for the establishment of speedy and permanent peace; to cherish all schools and seminaries of education, and to cause the knowledge of Christianity to spread over all the earth.

Done in Congress, the 18th day of October, 1780, and in the fifth year of the independence of the United States of America.] [7]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

No index entries found.

[1] Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "Arnold, Benedict."

[2] George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, Collected and Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford, 14 vols. (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1889-1893), 8:502.

[3] Washington, Writings of George Washington, 8:506.

[4] Washington, Writings of George Washington, 8:507.

[5] On Monday, October 16, 1780, the committee presented its draft for "a proclamation for setting apart a day of thanksgiving and prayer." However, it was not formally approved until two days later and even then, appears to have been altered at the end of the month. See Journals of the Continental Congress, 18:934.

[6] Journals of the Continental Congress, 18:919.

[7] It should be noted that the brackets used in these Journal entries have been inserted by the editors of congressional records—not this author. The bracketed portion was written by Samuel Adams in the original draft sent to Congress. Journals of the Continental Congress, 18:950-951.

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

Thanksgiving for Divine Providence

- 16

- 16shares