For generations of Americans, the memory of candles flickering at the close of watch-night services—as one year waned and another began to wax—is one that evokes reverent appreciation for the spiritual fervor of by-gone days. Though the observance of the watch-night service began to wane at the end of the twentieth century, its origin in both the British Isles and America are significant chapters in the spiritual life of these nations. In America, few realize the place that one watch-night service had in the birth of the nation. The origin and use of the watch-night service speaks volumes concerning the spiritual passions that once characterized these two nations. The facts behind the origin and progress of the watch-night service are important strands in the tapestry that recounts the Christian origin of America. The following details of one American religious observance relate a minuscule portion of the Christian influence that birthed America.Watch-night Service

Contents

The modern rise and use of the watch-night service, for the most part, may be traced to John Wesley and the Methodists. In a letter dated June 8, 1750, John Wesley, noted that the Anglican Book of Common Prayer made use of the word "vigil" to describe a practice observed by Christians in the early Church. In his letter, Wesley stated that it was common for early Christian believers to spend the entire night in prayer and that this practice was called Vigiliae or "vigils." He reasoned that this practice among the English Methodists was not original, but based upon the example of early Christians: "Therefore, for spending a part of some nights in this manner, in public and solemn prayer, we have not only the authority of our own national [Anglican] Church, but of the universal Church in the earliest ages."[] While Wesley is correct that the practice of praying throughout the night or a part of it may be traced to the early Church, the contemporary observance of the watch-night service may be traced to the English Methodists, particularly early converts of Methodism who came under the influence of Wesley and his preachers. An extended prayer meeting at night came to be known as a watch-night service.Watch-night Service

The first watch-night service was held at Kingswood, England sometime prior to April 1742, though the exact date cannot be determined. Following the evangelical conversion of John and Charles Wesley in May 1738, a spiritual awakening began to stir in the British Isles under their preaching and leadership. Some of the colliers (or coal miners) who received Christ as Savior in the town of Kingswood became burdened about the spiritual conditions of their families and community and began to spend Saturday nights in prayer. Their interest in prayer and spiritual matters were the natural results of genuine spiritual conversion that properly orients all of life. One writer relates their experience:

The custom [of the watch-night service] was begun at Kingswood by the colliers there, who before their conversion, used to spend every Saturday night at the ale-house. After they were taught better, they spent that night in prayer. Mr. Wesley hearing of it, ordered it first be once a month, at the full of the moon [to light their pathways], then once a quarter, and recommended it to all his societies.[]

Wesley's own account of the origin of the watch-night service provides additional insight to the strong spiritual desires that gave rise to this practice:

I was informed, that several persons at Kingswood, frequently met together, at the school [for miners' sons], and (when they could spare the time) spent the greater part of the night in prayer and praise and thanksgiving. Some advised me to put an end to this; but upon weighing the thing thoroughly, and comparing it with the practice of the ancient Christians, I could see no cause to forbid it. Rather, I believed, it might be made of more general use. So I sent them word, ‘I designed to watch with them, on the Friday nearest the full of the moon, that we might have light thither and back again.’ I gave public notice of this, the Sunday before, and withal, that I intended to preach, desiring they, and they only, would meet me there, who could do it without prejudice to their business or families. On Friday abundance of people came. I began preaching between eight and nine, and we continued until a little beyond the noon of night, singing, praying and praising God.[]

From this humble beginning of the watch-night service, the practice spread among the Methodists. By 1789, it was common practice to hold watch-night services until midnight in the British Isles.

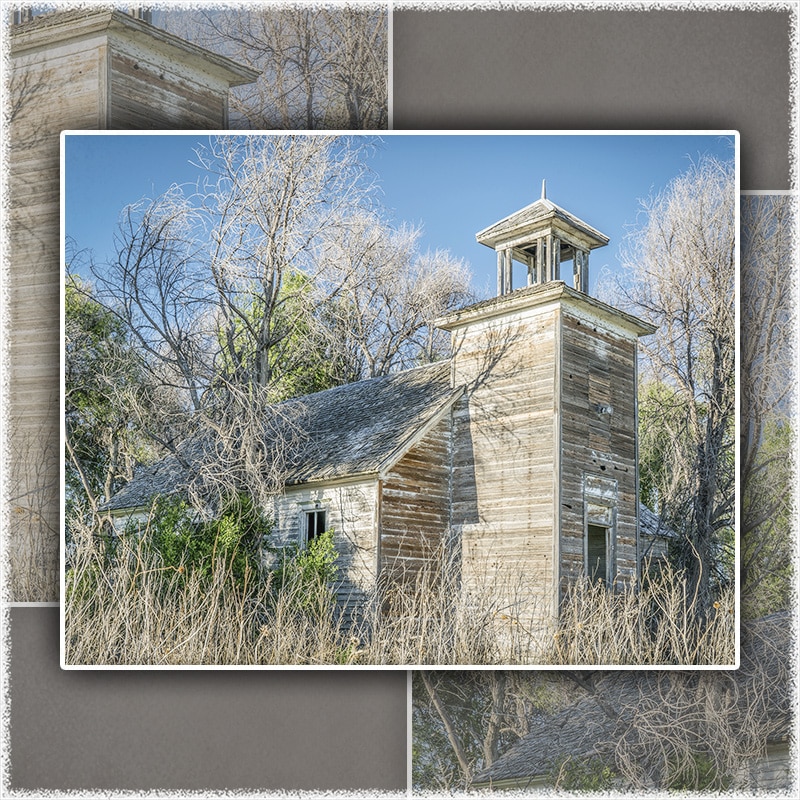

Nearly thirty years passed before the watch-night service was first observed by Methodists in America, in part, because so few Methodists had immigrated to America before 1770. By the end of 1770, the watch-night service had been held on at least three separate occasions. In August 1769, two of Wesley's preachers—Joseph Pilmore and Richard Boardman—had volunteered to come to America to preach. On November 1, 1770, Joseph Pilmore conducted the first watch-night service in America, convened at Old St. George's Church in Philadelphia. Two more watch-night services followed that year, the second being held on November 5 in New York. The third observance was held again in Philadelphia on December 31—the first time a watch-night service was held on a New Year's Eve in America. Not until sometime later were watch-night services held exclusively on New Year's Eve, but a very important one did follow several years later.

Americans Win Battle of Trenton

Many Americans recognize the image of George Washington standing in an open boat as oarsmen struggle to make way through a pack of ice. This 1851 oil-on-canvas painting by the German American artist Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze commemorates the crossing of the Delaware by General Washington and the main body of the American Continental Army during the night of December 25-26, 1776, landing just north of Trenton, New Jersey. Because the river was icy and the weather treacherous, the crossing of the Delaware proved dangerous, reducing the number under Washington's command for the assault to 2,400. Having crossed the Delaware, the army marched nine miles south to Trenton, surprising the Hessian garrison. Nearly two-thirds of the 1,500-man garrison was capture; their leader, Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rahl, paying with his life. Having suffered several defeats prior to the Battle of Trenton in New York, Washington had been forced to retreat through New Jersey. A week earlier, the American army appeared on the verge of collapse, but the Battle of Trenton and the few days that followed breathed hope into the American cause.

Watch-night and Washington's Army

Only a few years after its first observance in America, the watch-night service intersected with an important moment in American history. On December 26, 1776, General Washington enjoyed success against his British adversaries at the Battle of Trenton, New Jersey, and a few days later on January 3, 1777, he once again tasted victory in the Battle of Princeton. On December 31, 1776, General Washington was with his troops in Trenton, but one year later on the eve of a new year would find him in a very different circumstance.

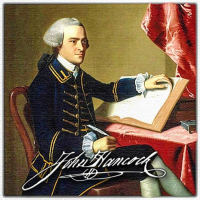

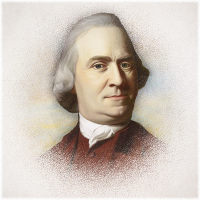

On December 31, 1777—a year after the Battles of Trenton and Princeton—a watch-night service was again held at Old St. George Church, Philadelphia. In attendance was Robert Morris, a Philadelphia banker and merchant, who was known as "the financier of the American Revolution." As 1777 waned into 1778, General George Washington was with his troops in Trenton, New Jersey. More than thirty miles lay between Philadelphia and Trenton, and in deep need of supplies for his troops, General Washington sent word to Robert Morris of the army's grave condition and pleaded for his assistance in raising $50,000. Receiving the request from General Washington, Morris set out long before daybreak for the homes of his friends, rousing them from their beds to request urgent contributions. Morris told his friends that he had just come from a watch-night service at St. George's Methodist Church where "prayers were being offered that God would open up the hearts of the people to furnish the money they needed to pay the troops at Valley Forge that the Army might be saved."[]

The prayers of those in attendance at the watch-night service at St. George Methodist Church on December 31, 1777 were heard and answered, and the necessary funds were raised. The following morning, January 1, 1778, Robert Morris sent the desperately needed cash to General Washington and his troops. The American army was saved and after four more years of war, finally realized victory.

Like many of America's Founding Fathers, Robert Morris experienced tremendous personal loss as a result of his support for the American Revolution. Because of his faithfulness to the cause of freedom from lawless tyranny, America experienced a new birth. In the present generation, God needs men and women who will be as faithful to truth as was Robert Morris!

Indeed, many similar accounts of answered prayer at the birth of America could be recounted. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, God's expectations for spiritual renewal and blessing are no less exacting today than they were in the days of America's Founding Fathers or the age of the Apostles. If America is to enjoy renewed spiritual life, it must once again acknowledge dependence and continual reliance upon the grace of God, seeking His highest willingness for the nation. Earnest repentance and prayer have always preceded the greatest movements of God in world and American history. May the earnestness of prayer that has characterized the very best moments of spiritual awakening throughout the history of Christianity again characterize the prayer life of true believers!

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[] To Rev.John Baily of Kilcully, Cork, Letters 3:287; quoted by Frederick E. Maser, "Watch-nigh," Encyclopedia of World Methodism (Nashville: The United Methodist Publishing House, 1974), 2:2465.

[] William Myles, A Chronological History of the People Called Methodists, of the Connexion of the Late Rev.John Wesley; From Their Rise, in the Year 1729, to Their Last Conference, in 1812, 4th ed. (London: Printed at the Conference Office, 14, City-Road, by Thomas Cordeux, []), []; quoted by Frederick E. Maser, "Watch-nigh," Encyclopedia of World Methodism (Nashville: The United Methodist Publishing House, 1974), 2:2465.

[]Ibid. Given the fact that in his Journal Wesley records the date for the first watch-night service in London was held April 9, 1742, he must have met with those in Kingswood prior to this date.

[] F. H. Tees, Methodist Origins (1948): 149; quoted by Frederick E. Maser, "Watch-nigh," Encyclopedia of World Methodism (Nashville: The United Methodist Publishing House, 1974), 2:2465.