One need not scour Scripture too carefully to locate numerous divine responses to prayer. Abraham pled for divine mercy for the towns of Sodom and Gomora, and though the limits of justice were tested, God answered Abraham’s prayer for mercy. The lives of Moses, Hanna, Samuel, David, and many others—in both the Old and New Testaments—received divine responses to their earnest prayers.The Prayer Meeting That Saved England

And, just as the pages of Scripture recount God’s answers to prayer, so Church history also records the outpouring of God’s Spirit in response to the pleas of His people. The great revivals of the Church and subsequent social reforms are among the vivid examples of answered prayer. One remarkable example of the power of prevailing prayer occurred in the British Isles as the year 1738 waned and 1739 waxed.

This article is one we have featured in our newsletters. To subscribe and receive our newsletters, please click the link: Signup...

Article Contents

July 14, 1789 is regarded by many historians as the start of the French Revolution. Unlike the American Revolution which was influenced by Christian principles, the French Revolution was birthed by the godless principles of François-Marie Arouet (known as Voltaire), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many others of like mind. It is estimated that well over 900,000 lost their lives between 1789 and 1815 under the godless blood-letting influences of these pretentious French thinkers. In his work, The Origin and Principles of the American Revolution Compared with the Origin and Principles of the French Revolution, Friedrich Gentz described the great differences between the two revolutions.

But the irreligious influences of Voltaire, Rousseau, and company reeked tyranny not only upon individual lives but also upon the nation of France for generations to come. As is true wherever godless principles are permitted to influence government, great instability in society resulted. During the period of time that America has existed under one Constitution, the French people have experienced the instability of sixteen constitutions and governmental reforms; the average lifespan of French constitutions has been less than fifteen years.

Fifty years lapsed between a New Year's Eve prayer meeting in England that continued well into the early morning hours of January 1, 1739 and the bloody massacre of the French Revolution. Churchmen and historians have believed that this prayer meeting was part of a larger collage of spiritual life that saved England from the French Revolution and its bloody "Reign of Terror." It is believed that the same blood-letting that occurred in France against the monarchy, the church, and nobility would very likely have occurred in England had it not been for the Evangelical Awakening in England which was realized most vividly under the lives and ministries of John and Charles Wesley and their companions in this renowned spiritual awakening. The love-feast and prayer meeting of Sunday evening, December 31, 1738 and opening hours of Monday morning, January 1, 1739 served as a spiritual inauguration for the public ministry of the Wesleys and Methodism.

For years, John Wesley and his brother Charles had attempted to make themselves acceptable to God through their good works—which would put to shame most contemporaries who profess a saving knowledge of God. They had visited prisons, diligently studied Scripture in the original languages, received the Lord's Supper several times a week, and ardently pursued conformity to external spiritual expectations, but they did not receive the witness of God's Holy Spirit that they were accepted into God's favor. Following graduation from Oxford and entrance into the Anglican ministry, the Wesley brothers ventured to America at the invitation of General James Edward Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia Colony.

Discouraged and disappointed, both men returned to England by January, 1738, but without spiritual peace. Under the influence of the Moravians en route to America as well as following their return to England, both Charles and John experienced their evangelical conversions through a living faith in Christ Jesus as Savior—only days apart from each other in May of that same year. Later in 1738, John traveled to Germany to the estate of Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf (Moravian patron) to witness the spiritual life of the Moravian community.

By the close of 1738, John Wesley had returned to England from Germany and his visit to the Moravians, and in the closing hours of that year, Wesley gathered with others at Fetter Lane to pray and participate in a love-feast. Throughout his life, Wesley kept a journal, and he recorded the events of that meeting in the entry for January 1, 1739:

Mr. Hall, Kinchin, Ingham, Whitefield, Hutchins, and my brother Charles, were present at our love-feast in Fetter-Lane, with about sixty of our brethren. About three in the morning, as we were continuing instant in prayer, the power of God came mightily upon us, insomuch that many cried out for exceeding joy, and many fell to the ground. As soon as we were recovered a little from that awe and amazement at the presence of his Majesty, we broke out with one voice, "We praise thee, O God; we acknowledge thee to be the Lord." [1]

Many may wish to interpret this experience in charismatic terms, but they are completely unjustified in doing so. The Wesleys' lives and ministries from this point forward increased in power and usefulness, extending to all the British Isles, and through the Methodists, to America. From the beginning of Methodism in the late 1720s, while the Wesley brothers were still at Oxford, to the end of their days, the Wesleys believed that God had raised them up to "spread scriptural holiness over these lands."[2] In nineteenth-century America, the message of Christian purity established Methodism as the largest Protestant denomination in the land. Not since the early Christian Church had such evangelical stress been placed upon the need for Christian purity, as was emphasized by the Methodists of those early generations. As a result, eighteenth-century England witnessed a remarkable spiritual awakening that historians believed saved the British Isles from a bloody revolution similar to that which the French experienced at the hands of the deists, agnostics, and atheists.[3]

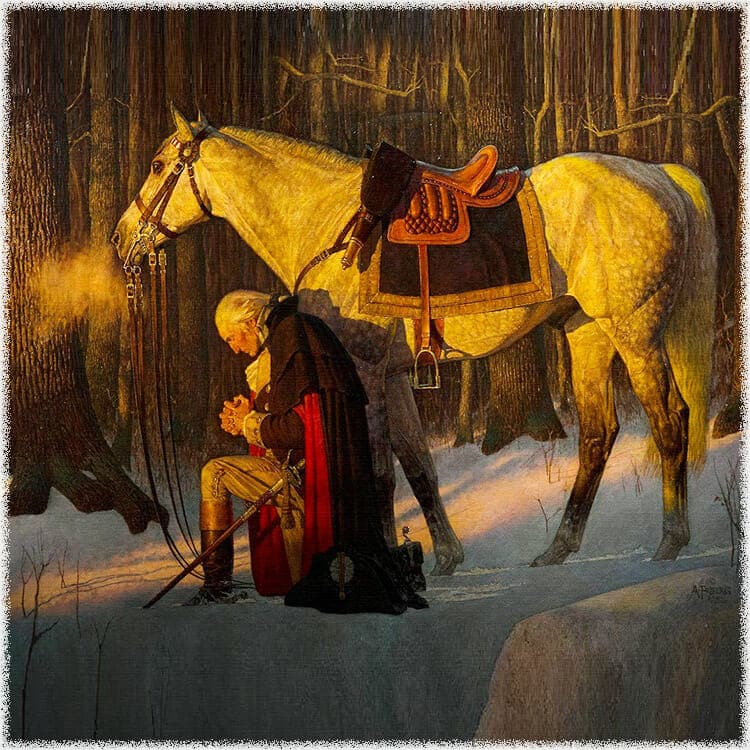

Great movements of God have nearly always been preceded and accompanied by great moments of prayer. In America, the American Revolution was preceded and established upon the First Great Awakening, and when pastors and church leaders had given their lives upon the battlefields of the Revolution and a spiritual vacuum resulted, the Second Great Awakening (1790s and following) gave new life to the Christian Church in the newly-birthed nation—because of prayer. The Revival of 1859 removed the spiritual tarnish from the hearts of many Americans and was the reason for revival in the British Isles later in that same century and the early twentieth century.

Few Americans have previously witnessed the level of moral and spiritual darkness that now grips our nation. This darkness now casts its shadow upon America and nations around the world, and if nations are to be spared the consequences of this midnight, Christians must find once again what Wesley and the other congregants of Fetter Lane found on December 31, 1738 and the opening hours of January 1, 1739—the primacy of prayer! England was spared the darkness and devastation of a French-styled revolution, but America and other nations around the world in this dark era of history will not be if Christians fail to turn and pray. By God’s grace we must be found faithful to the generation to which our Lord has entrusted us!

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] John Wesley, Works of Wesley (London: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room, 1872; Grand Rapids: Baker Book House Company, 1986), 1:170.

[2] A Form of Discipline for the Ministers, Preachers, and Members of the Methodist Episcopal Church in America (New York: W. Ross, 1787; repr., A Reprint of the Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church for 1787 (Clevland, OH: W. M. Bayne Printing Co., 1900)).

[3] See Elie Hal. . . vy, Histoire Du Peuple Anglais Au Xixe Siècle (Paris: Hachette et cie, 1913). For the English translation, see . . . lie Hal. . . vy, The Birth of Methodism in England, trans. Bernard Semmel (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971).