Preacher Becomes First Speaker of Congress

Among the thousands of pieces of evidence that prove America was not founded as a secular nation are events relating to the transition of the Continental Congress[1] to the United States Congress under the Constitution. If the Founding Fathers had been secularists, they never would have incorporated the seven distinct Christian observances employed in the inauguration of George Washington. Neither would they have installed Christian ministers as chaplains, first in the Continental Congress, and then in both houses of the United States Congress. To this brief—but important—list could be added many more observances—many of which we seek to note here at Christian Heritage Fellowship, Inc. And, to the list of facts that demonstrate America was initiated as a Christian nation, notice should be paid to the individual chosen as the first Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Article Contents

Beginnings of America's Federal Government

Prior to the organization of the United States Congress under the Constitution, the Continental Congress, which served as America's earliest form of federal government, passed through three stages of development. Those three periods of development are often designated by one name—the Continental Congress—which spanned a period from 1774 to 1789. Historians often referred to one or more of the three specific periods of development within these fifteen years as the First Continental Congress, Second Continental Congress, and the Confederation Congress.

The First Continental Congress—the shortest of all three—was convened from September 5 to October 26, 1774 at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with twelve of the Thirteen Colonies represented by delegates.

The Second Continental Congress was represented by delegates from all Thirteen Colonies and convened from May 10, 1775 to March 1, 1781. Due to varying circumstances, the Second Continental Congress was convened in different locations.[2]

A third step in the development of America's federal government was the Congress of the Confederation (extending from March 1, 1781, to March 4, 1789). The Congress of the Confederation was succeeded by the United States Congress under the Constitution in 1789.[3]

Implementation of United States Constitution

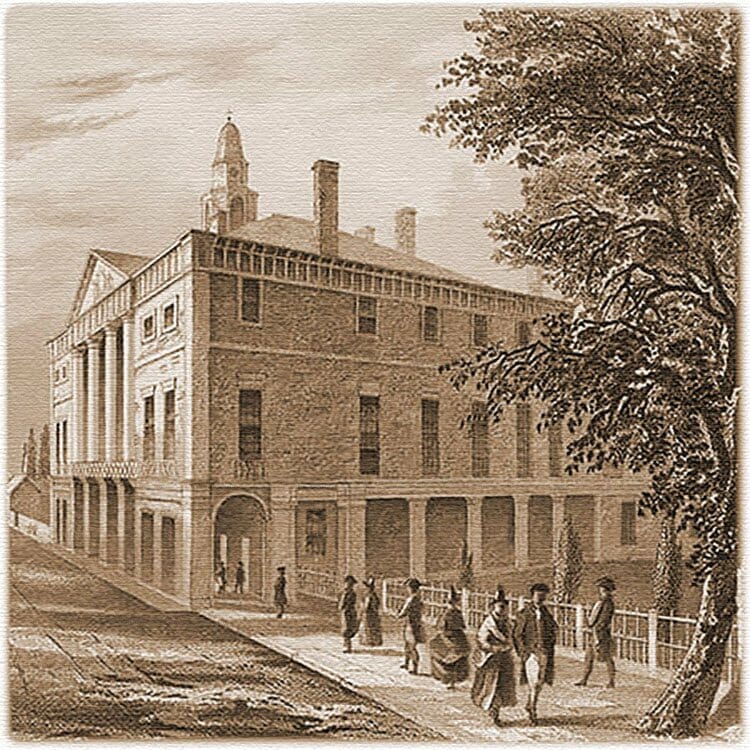

The Confederation Congress received and submitted the new Constitution document to the states, and the Constitution was later ratified by enough states (nine were required) to become operative by June 1788. On September 12, 1788, the Confederation Congress set the date for choosing the new Electors in the Electoral College that was set up for choosing a President as January 7, 1789, the date for the Electors to vote for the President as on February 4, 1789, and the date for the Constitution to become operative as March 4, 1789, when the new Congress of the United States was to convene. It was decided that at a later date the time and place for the Inauguration of the new first President of the United States would be set by the new Congress.[4] The place designated for the new Congress to convene was Federal Hall in New York City, but as they discovered, it was easier to dictate details than it was to live up to them.

House and Senate Begin Work in April

Though some members of the House of Representatives and Senate convened on the date designated by the Confederation Congress (March 4, 1789), too few were able to be there on that date, and for this reason a quorum could not be established to begin the work under the new Constitution. Not until nearly a month later—on April 1—was the House of Representatives able to achieve a quorum. On April 6, the Senate achieved a quorum for the first time. That day the House and Senate met in joint session and the electoral votes were counted—certifying George Washington and John Adams as president and vice president respectively.

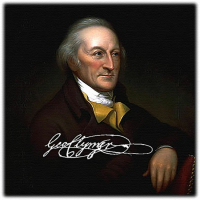

Preacher Elected First Speaker of Congress

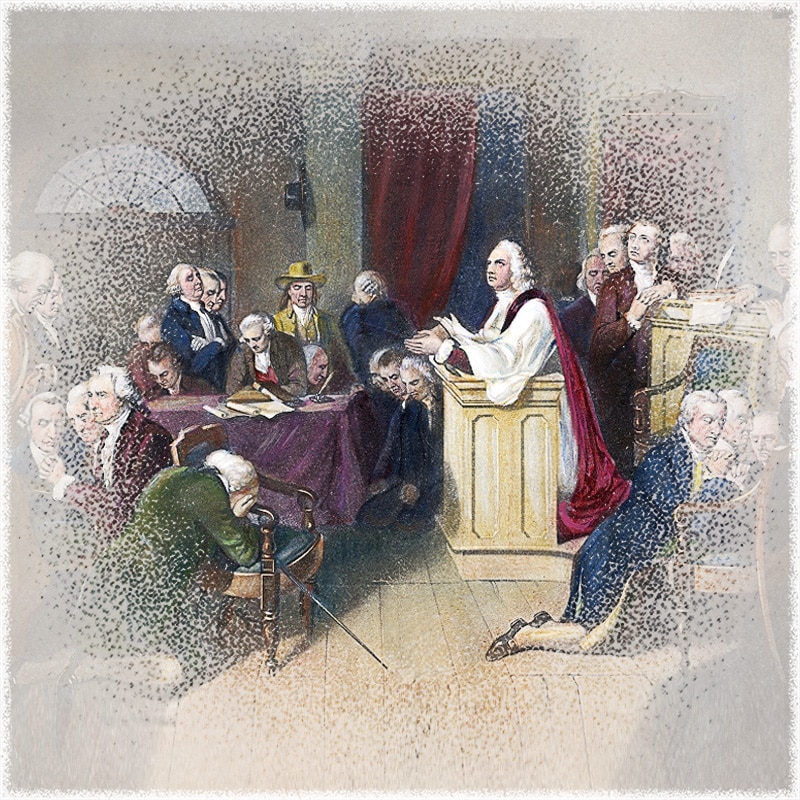

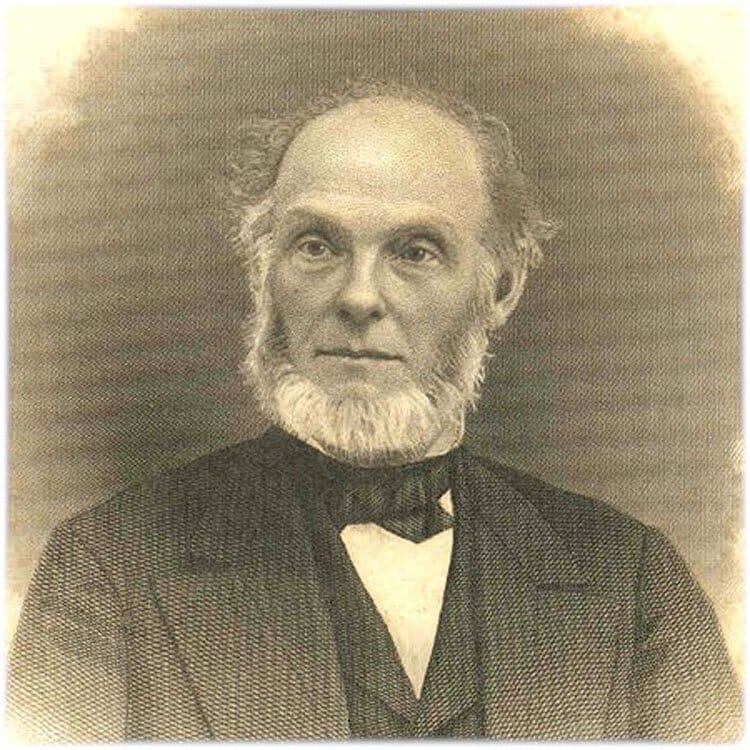

The Battle of Long Island (also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights) was fought on August 27, 1776. It was the first major battle of the American Revolution following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, nearly two months earlier. Resulting in a victory for the British, the Battle of Long Island gave the conquerors control of New York City. During the bombardment of the city by the British, the Lutheran Christ Church[5] had been burned, driving its pastor, Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, and his family from the city.[6] Regarded as unsettled in his commitment to the American cause of independence prior to this battle, Frederick quickly identified with his fellow countrymen following this event.

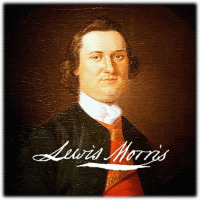

Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg was the son of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, who is regarded as the founder of the evangelical Lutheran Church in America.[7] In January of 1776, Frederick's brother, John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg (also a pastor), had exchanged his black clerical robe for the uniform of a colonel in the American Revolutionary Army.[8] Attaining the rank of brigadier general, John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg became one of the most distinguished soldiers of the American Revolution. For this reason, he has been honored with a statue in the United States Capitol. While Rev. John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg was to become one of America's great soldiers, his brother, Rev. Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg was to become one of the nation's most distinguished political figures.

Three years after the burning of his church by the British, Frederick Muhlenberg became a member of the Continental Congress, serving from 1779 to 1780. In 1780, he became a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and elected that same year as speaker of that chamber.

Like Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon, president of Princeton and signer of the Declaration of Independence, the ministerial voice of Frederick Muhlenberg was one of the first in Pennsylvania to call for a new form of government other than what was provided in the Articles of Confederation. In the summer of 1787, the Constitutional Convention was convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. When the state of Pennsylvania took up the question of ratifying the proposed Constitution in November 1787, it elected a Christian minister to chair its convention—none other than Rev. Frederick Muhlenberg. With the influence of Frederick and John Peter Muhlenberg and others in favor of the new Constitution, Pennsylvania ratified it by a vote of 46 to 23. Three days later, on December 15, 1787, Rev. Frederick Muhlenberg, "President of the Convention of Pennsylvania," sent a letter to the President of the Continental Congress, announcing the fact that the state of Pennsylvania had ratified the Constitution.[9]

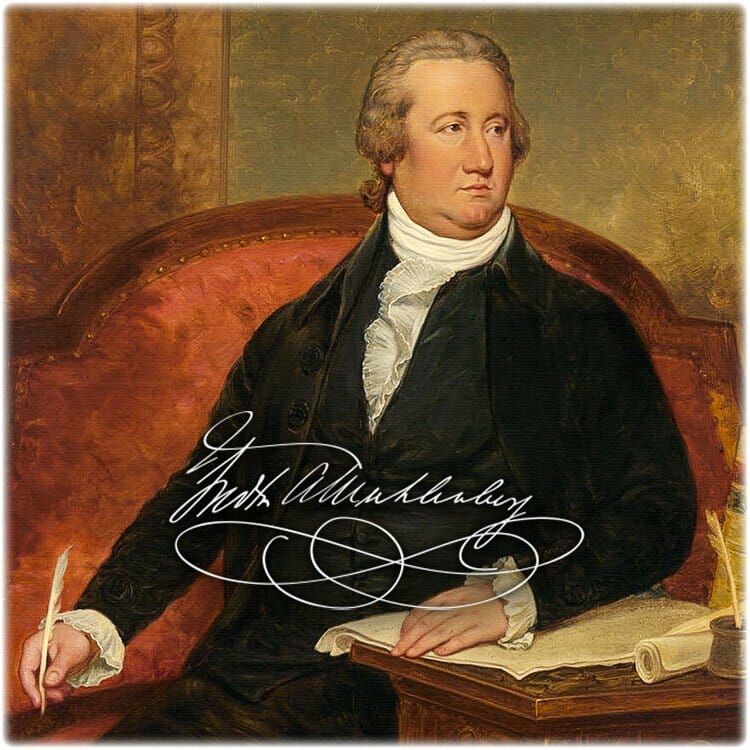

Under the stipulations of the new Constitution, the state of Pennsylvania was to send eight members to sit on the new Congress, and among the eight chosen from Pennsylvania by the state assembly were Frederick and John Peter Muhlenberg. Thirteen years after he was forced to flee New York City, Frederick Muhlenberg returned to occupy a unique position under the new Constitution. After nearly a month of delay due to the inability to convene a quorum for business in the House of Representatives, two new members of the House arrived in New York. The minutes for that momentous day of Wednesday, April 1, 1789 read,

Two other members, to wit: James Schureman, from New Jersey, and Thomas Scott, from Pennsylvania, appeared and took their seats.

And a quorum, consisting of a majority of the whole number, being present,

Resolved, That this House will proceed to the choice of a Speaker by ballot.

The House accordingly proceeded to ballot for a Speaker, and upon examining the ballots, a majority of the votes of the whole House was found in favor of Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg, one of the Representatives for the State of Pennsylvania.

Whereupon, the said Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg was conducted to the chair, from whence he made his acknowledgments to the House for so distinguished an honor.[10]

On two separate occasions, Rev. Frederick Muhlenberg served his country as the Speaker of the House of Representatives (April 1, 1789 - March 4, 1791 and December 2, 1793 - March 4, 1795).[11]

King George III regarded the preachers of America as the influence behind the American Revolution. And, because of the black pulpit robes worn by some early American ministers, King George called the Revolution a "Black-robe Rebellion." There is no evidence to suggest that America was founded as a secular nation. All historical evidence points to the facts that America's Founding Fathers understood that governments without God always become tyrannical! For this reason, America's Founding Fathers sought to establish their nation upon the republican principles of the Bible. Rev. Frederick Muhlenberg—the first Speaker of the House of Representatives of the United States—reflected the Founding Fathers' understanding of the relationship of Christianity to government in a letter to his brothers, dated October 1780:

The coffers are empty, the taxes almost unendurable, the people are in a bad humor, the money discredited, the army magazines exhausted, and the prospect to replenish them poor; the soldiers are badly clad, winter is coming...taking this and other things into account, public service might appear undesirable. However, let us one more take cheer and be steadfast, rely on God, and our own strength, and endure courageously, then we shall after be sure of reaching our goal.[12]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

[1] The latter phase of the Continental Congress is generally known as the Confederation Congress, extending from 1781 to 1789.

[2] The venues the Second Continental Congress include the Pennsylvania State House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (May 10, 1775 – December 12, 1776), Henry Fite House, Baltimore, Maryland (December 20, 1776 – February 27, 1777), Pennsylvania State House, Philadelphia (March 5, 1777 – September 18, 1777), Court House, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (September 27, 1777—only one day), Court House, York, Pennsylvania (September 30, 1777 – June 27, 1778), College Hall, Philadelphia (July 2, 1778 – July 20, 1778), and Pennsylvania State House, Philadelphia (July 23, 1778 – March 1, 1781)

[3] This third development occurred through the efforts of the Second Continental Congress which transpired over a period of several years. On June 12, 1776—the day after the Committee of Five was appointed to prepare a draft of the Declaration of Independence—the Second Continental Congress appointed a thirteen-member committee to prepare a draft of a constitution that would bind the Thirteen States into a union. This early constitution was known as the Articles of Confederation. On July 12, 1776, a month after receiving their commission to draft the Articles of Confederation, the committee presented their results to Congress. The final draft of the Articles of Confederation, however, was not approved for ratification by the states until November 15, 1777. In practice, however, the Articles were implemented at the beginning of 1777, but were not final until March 1, 1781, following the ratification of Maryland one month earlier, on February 2. The Congress of the Confederation was succeeded by the United States Congress under the Constitution in 1789.

[4] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 34:518.

[5] The Christ Church was also known as the Swamp Church, now in Manhattan. "Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg," Grey House Publishing, March 31, 2017; http://www.greyhouse.com/pdf/speaker_pgs.pdf.

[6] Henry Eyster Jacobs, A History of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States (New York: Christian Literature Co., 1897), 300.

[7] Henry Muhlenberg was sent to America by well-known Pietistic leader of Halle University, Gotthilf August Francke. Daniel Reid, Robert and et al, Dictionary of Christianity in America. s.v. "Muhlenberg, Henry Melchior (1711-1787)"

[8] Oswald Seidensticker, "Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, Speaker of the House of Representatives, in the First Congress, 1789," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 13 (1889): 190, accessed March 31, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20083312.

[9] "Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg," Grey House Publishing, March 31, 2017; http://www.greyhouse.com/pdf/speaker_pgs.pdf.

[10] Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, Being the First Session of the First Congress: Begun and Held at the City of New York, March 4, 1789, and in the Thirteenth Year of the Independence of the Said States, 43 vols. (Washington: Printed by Gales & Seaton), 1:6.

[11] During his second tenure as Speaker (in 1794), the House of Representatives voted 42 – 41 against translating America's laws into German. Later Muhlenberg commented, "the faster the Germans become Americans, the better it will be." See "German as the official language of the USA‒," Spiegel Online (March 31, 2017, http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/zwiebelfisch/onionfish-german-as-the-official-language-of-the-usa-a-306711.html).

[12] "Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg," Grey House Publishing, http://www.greyhouse.com/pdf/speaker_pgs.pdf.