Patrick Was a Christian Missionary

Like St. Nicholas, St. Patrick is more readily known through the lens of contrived folklore than through what may more accurately be determined concerning his life and ministry. Accompanying the expansion of Christianity was a desire to demonstrate the superiority of the Christian faith to an unbelieving world. Often nominal Christians developed stories about the heroes of Christianity so as not to be outdone by pagans who, likewise, contrived heroic stories of their gods. Just as the Church of the Book of Acts witnessed the miraculous manifestation of the work of the Holy Spirit in healings and other supernatural acts, there is no reason to doubt that God, in a similar way, demonstrated the truthfulness of the message which Christian missionaries took to pagan cultures through similar miracles. What is suspect is the nature of some of the miracles which the “saints” of the church are alleged to have performed.

The following pages are not intended to be exhaustive of the life and ministry of Patrick, Apostle to the Irish. Rather, they are an attempt to introduce readers to one of the best known missionaries of the Christian Church.

Table of Contents

I arise today with God’s strength to pilot me:

God’s might to uphold me; God’s wisdom to guide me

God’s eye to look ahead of me; God’s ear to hear me

God’s work to speak to me; God’s hand to defend me

God’s way to lie before me; God’s shield to protect me

God’s host to safeguard me: against devil’s traps

against attraction of sin; against pull of nature

against all who wish me ill, near and far

alone, and in a crowd

. . .

Christ ever with me, Christ before me,

Christ behind me, Christ within me,

Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ to my right side, Christ to my left,

Christ in his breadth, Christ in his length, Christ in depth,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.[1]

These words, attributed to St. Patrick, are a prayer for divine protection of the minister of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. And certainly the Christians of the British Isles of Patrick’s day needed divine protection against the fierce attacks of Satan.

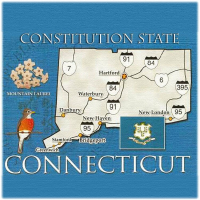

In 55 B.C., the Roman Empire conquered a large portion of present-day England, then known as Briton. The Roman armies were led by Julius Caesar, who was at that time general of the Roman armies in Gaul (which is modern-day France). A barbarian people known as the Celts fought against the Romans in Gaul and received assistance from fellow Celts in Briton. For this reason, Julius Caesar decided to attack the Celts in Briton. For more than four-hundred years following Julius Caesar’s wars in Briton, the Roman armies maintained a foot-hold in that country.

Exactly when Christianity first reached the British Isles is unknown. It is clear, however, that by the late third or early fourth century, the British Isles were evangelized. Christians in the British Isles regarded themselves as independent of the authority of the pope of Rome. Christianity was less than a hundred years old in the British Isles when the protection it enjoyed by the presence of the Roman legions was swiftly removed. About the year 410, the Roman armies were withdrawn from the British Isles to protect the capital city of Rome from the murderous advance of the barbarians, who were themselves being pushed into the Roman Empire by Attila the Hun. Not being protected any longer by the Roman legions, Briton was raided by the barbarian tribes known as the Picts and Irish. Among those taken captive and enslaved by the Irish raiders was a teenager by the name of Patrick. Hear now his story from unbelief to a living faith in Jesus Christ is here recounted.

Popular Ideas About Patrick Rejected

“I have kept the faith” (2 Tim. 4:7). These were the words of the Apostle Paul to his son in the faith, Timothy, as the Apostle neared the time of his execution at the hands of Emperor Nero in Rome. These were Patrick’s words in defense of his ministry among the Irish to those who had come to the Emerald Isle to question his ability to lead. But then, few know little of who he was.

I. Who Patrick Was Is Not Well Known

Throughout Ireland, the United States, and other nations of the world Patrick’s life as a minister of the Gospel is celebrated on March 17th. But, like St. Nicholas, few truly know anything about the real Patrick, and even less about his ministry as a missionary to the Irish people.

II. Patrick Did Not Drive "Snakes" From Ireland

He is most widely regarded for having rid Ireland of all snakes, frogs, and toads. Irish folklore suggests that he gather all the reptiles from all Ireland into the western part of Connaught and drove them into the sea from the summit of Eagle Hill (since known as Croagh Pat). Whenever the snakes became disinclined to follow to the summit of the hill with him, legend suggests that he would ring his bell as an inducement. Then the snakes would quickly follow. At the very last moment, he is reported to have hurled his bell among the snakes at the summit of the mountain, persuading them to leap from the rocks into the sea where they all were reported to have perished.

Today, in Dublin, visitors to a museum are shown the very bell by which the snakes were driven out. It is unnecessary to state that he never drove the reptiles out of Ireland. The fact that there are no snakes in Ireland today is due to a geological, not a theological reason. The reason Patrick’s name is associated with the driving out of reptiles in Ireland may be attributed to his work against the Druid pagan worship. Ophiolatry, or serpent-worship, has been a widespread practice among primitive people groups around the world. Serpent-worship was also practiced among the Druids and their followers. Patrick vigorously opposed the Druids and their pagan religious practices. He sought to drive out the Druids with their serpent- and demon-worship, and because of this, Irish folklore has associated Patrick’s efforts as a Christian missionary with having driven the reptiles out of Ireland. The only reptiles which he sought to drive out of Ireland were the Druids and their serpent-worship.

It was Jocelyn, a monk from the abbey at Inch (in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries), who, in a biography of Patrick, began the myth of the Apostle to the Irish ridding Ireland of its snakes. This type of story was designed to make Patrick appear more powerful than he was. In fact, two centuries prior to Patrick’s life, the Roman writer, Solinus, commented that there were no snakes in Ireland.[2]

III. Patrick Did Not Wear Clerical Attire

One of the most persistent images of Patrick is that of a bishop wearing clerical attire and holding a crosier (bishops staff). But this attire was not worn until the seventh and eighth centuries. His ministry preceded this period by three to four centuries. He did not wear clerical attire. He wore a plain tunic, usually made of wool. The shamrock, so frequently associated with Patrick, was also an invention of a much latter period.[3]

IV. Patrick Was Not Irish Or Roman Catholic

Many believe that Patrick was an Irish Catholic, but he was neither Irish nor Roman Catholic. He was a Briton by birth, and in Patrick’s day, the Briton church was Celtic (pronounced kel-tik or sel-tik)—not dominated or controlled by the Roman Catholic Church. Ireland was one part of European environs which had never been part of the Roman Empire. Therefore, Celtic Christianity was not associated with the Roman hierarchy. Christianity spread throughout Ireland by individual Christian leaders rather than an orchestrated effort.

V. Patrick Was a Christian Missionary to The Irish

Patrick wished to be remembered for who he truly was. Patrick was a Christian missionary to Ireland. After the Apostle Paul, he was the next great missionary in the Christian Church, even though he was born nearly three centuries after the Apostle to the Gentiles.

I. His Birth (ca. 389)

Patrick was born over 1,600 years ago to a Christian Celtic family.[4] His father, Calphunius, was a deacon in their local church, while his grandfather, Potitus, was a presbyter. Patrick’s father was a farmer, owning property near the village of Bannavem Taburniae.[5] In addition to his responsibility as a farmer and deacon in the local church, his father was a decurio, a member of the town council under the administration of the Roman colonial governors.

Despite the Christian environment in which he was raised, Patrick rejected the religious commitments of his parents and grandparents until after he was forced into slavery among the Irish in his mid-teens.

II. Forced into Slavery (ca. 405)

When about sixteen, Patrick was kidnapped by a band of marauding pirates, taken to Ireland, and sold into slavery. Following his purchase by his Irish master, Patrick was taken to a district in ancient Ireland called Tirawley, in the vicinity of modern Killala in the northern portion of County Mayo. Here he served his master as a shepherd in very trying circumstances. As might be expected, his enslavement interrupted his education. Because of this, Patrick remained ever sensitive to his academic limitations. A self-perceived lack of intellectual inadequacy remained a looming specter throughout his life.

III. Conversion in Slavery

Rather than destroying him, adversity became an instrument of refinement which determined his life’s course. From childhood, he had not come to believe in the living God; he remained in death and disbelief until he was humbled by gnawing hunger and nakedness of his captivity.[6] Like so many before and since, suffering was the instrument which opened Patrick’s eyes to the frailty of life; only after the suffering of slavery was he willing to make room in his thought and life for a Christian world view. While a shepherd for his master, the faith of his parents now became his faith. As he drew upon the Christian teachings of his childhood, he grew steadily in his faith, even among the heathen Irish. God became his Anam-cara. Anam is the Irish word for soul, and cara is the word for friend.[7] In his words, God became the “friend of my soul.” In time, it became the habit of his life to practice the presence of God.

. . . He was made to shepherd the flocks day after day, and, as I did so, I would pray all the time, right through the day. More and more the love of God and fear of him grew strong within me, and as my faith grew, so the Spirit became more and more active, so that in a single day I would say as many as a hundred prayers, and at night only slightly less. Although I might be staying in a forest or out on a mountainside, it would be the same; even before dawn broke, I would be aroused to pray. In snow, in frost, in rain, I would hardly notice any discomfort, and I was never slack but always full of energy. It is clear to me now, that this was due to the fervor of the Spirit within me.[8]

IV. Escape from Captivity (411)

After six years of captivity, Patrick believed he was impressed by God’s Spirit to escape from his Irish master. One night he had a dream in which he heard a voice speak: “You are right to fast, soon you will be returning to your own country.” A short time later, he heard another voice say, “Come and see where your ship is waiting for you.” He interpreted these impressions as God's message to break his bondage and make his way to the coast where he could find passage away from Ireland. In obedience to these impressions, Patrick soon fled his duties as a shepherd and began a two-hundred mile journey to the coast of Ireland.[9] Not knowing his destination, Patrick meandered through the Irish countryside to the coast with confidence his steps were being ordered by God.

The day he reached the harbor, he observed a ship being put into the water from dry dock. He approached the sailors of the ship, told them he had enough money to set sail with them, but the commander of the ship wanted nothing to do with Patrick, saying, “Don’t get ideas into your head and imagine you are coming with us!” Turning to walk away, Patrick began to pray, but before he could clearly focus his prayer, one of the sailors called after Patrick: “Hurry up, these men are shouting out for you.” He immediately returned to the ship and to a different climate toward his request for passage. The crew now welcomed him, saying, “Come aboard, we will take you as you are; make friends with us how you will.” With a fervent spirit, he determined at that moment that he would not fall into their pagan ways with them. He hoped that they would come to faith in Jesus Christ, and soon afterward, he set sail.

Three days later they reached land,[10] then Patrick and the ship’s officers and crew walked for twenty-eight days through a barren landscape. Their food supply was soon exhausted, and for want of food, many of the sailors had to be left behind along the roadside. In frustration the commander complained to Patrick, “What have you to say for yourself, Christian? You boast that your God is all-powerful. So why can’t you pray for us—you know how badly hunger threatens us; it’s beginning to look as if we may not survive to see another living soul.” With confidence, Patrick told them to turn in trust to his God and put all of their faith in Him, because nothing was impossible for him. Patrick further announced that God would send a sufficient supply of food for their journey that very day. Suddenly, a wild herd of pigs appeared on the road in front of them. Wasting no time, the sailors began to kill a large number of them; and then they camped for two nights, feasting all the while on what God had supplied. Those who had been left behind along the roadside were also given of the bounty which God supplied, and after all had consumed their fill, they gave sincere thanks to God for their provisions. Though this incident commended Patrick to the sailors, he came to regard himself as a captive once again. Patrick then professed an impression was given to him by God which Patrick interpreted: “You will stay with these men for two months.”

V. Return Home

Continuing their journey, the group finally arrived at a village ten days following their great feast. On the sixtieth night after Patrick had received the revelation that he would be released by the sailors within a period of two months, Patrick observed, “the Lord delivered me from their hands.”[11] Escaping from the company of the seamen, he soon found his way back home to his own village, where his parents joyfully welcomed Patrick as their long-lost son.[12] After years of suffering with the abduction of their young son, they pleaded with Patrick never to leave them again.[13]

But only a short time passed before Patrick received a vision of a man who appeared to come from Ireland. The man in Patrick’s vision was identified by the name Victoricius, and he carried countless letters, one of which he handed to Patrick. He read it aloud, but it was not the voice of one he heard as he read, but many: “The voice of the Irish. Holy broth of a boy, we beg you, come back and walk once more among us.” The voice he heard in his dream was the voice of those with whom he had lived beside the forest of Foclut. His heart was so deeply pierced by the vision that he could finish the letter. This vision was to become one of the most formative moments of his life. Throughout the rest of his life, he would never forget the pleading voice of the Irish that he heard in that vision.

VI. Study in Gaul

The vision of that night set Patrick’s life upon a new course, though he did not return to Ireland immediately. By this time, the Roman legions had left the British Isles (in 410) in a desperate attempt to save the city of Rome itself from invading barbarians. As a result, inhabitants of the British Isles were forced to fend for themselves against other groups of barbarians which began to swarm the British Isles, filling the vacuum created by the vacating Romans.

Before Patrick returned to Ireland, he prepared himself for the ministry that awaited him by traveling to Gaul (modern-day France). Here he met Christian leaders who distinguished themselves by their spiritual and virtuous lives.[14] Returning to Britain, Patrick was ordained a deacon by fellow Christian in Britain. Following this, he made his way to Ireland, leaving behind forever his parents and natal country.[15]

VII. Return to Ireland

Upon Patrick’s return to Ireland, he face great opposition. On at least twelve different occasions, he found himself in such threatening circumstances that he felt he would loose his life. But the Lord brought Patrick through them all. He had resolved to live completely for Christ: “. . . I am ready and willing to give up my own life, without hesitation for his name.”[16]

VIII. Apocryphal Accounts of His Ministry

Tragically, very little historical evidence exists to deduce an accurate account of Patrick’s ministry in Ireland. As was true for St. Nicholas and many other early Christians, faithful believers who admired his life, and who had little clear evidence of his ministry, little by little began to mingle imaginative accounts of his life with the factual to such an extent that it became very difficult to distinguish truth from error. The earliest biography of Patrick was written in the Book of Armagh.[17] But it contained much that was not true. By the seventh century, much of Ireland had come under the influence of Christianity, but the old pagan ways had not been totally forsaken. Great mystical tales, such as the Tain bo Cuailnge, were still being told. These stories depicted ancient pagan rulers of Ireland as possessing supernatural abilities. Christians, feeling a necessity to compete with these magical stories, began to embellish Patrick’s life to inspire and capture the imagination of those who remained pagan. It was Christians’ way of saying, “Our God and holy men are better than yours!”[18] Some of these alleged accounts are recounted below.

A. Chief Dichu Converted

These apocryphal stories suggest Patrick possessed supernatural powers from the time he return to Ireland. He landed, they suggest, where the river Vartry flows into the sea at Wicklow, and when Patrick and companions landed, they cruelly mistreated by the citizens of the town of Wicklow when they landed. The citizens showered Patrick and those accompanying him with stones, resulting in the loss one of his companion's front teeth. The alleged account further suggests that he continued his missionary activity, traveling north, along the coast of Ireland. Finally, at the mouth of the Slaney River in County Down, he made his first convert, Dichu, a local chief. Out of gratitude, Dichu is said to have provided Patrick with a barn in which to hold worship services. That barn became his first church in Ireland.

B. Chief Milchu Destroys Himself

From here, Patrick is believed to have set his sights upon Chief Milchu and his palace, where Patrick had once spent some time as a slave. Having been warned by his pagan Druid priests (see image at right) that he was coming and that his former servant would triumph over him, Chief Milchu reportedly set fire to all his household goods and perished in the midst of them just as Patrick arrived. This event made Patrick realize that if the Gospel was going to spread among the Irish, he would have to confront the bloody pagan religion of the Druid priests.

C. King Loaghaire Converted

Patrick is believed to have proceeded to attempt to crush the serpent of the religion of the Druids by confronting them in the city of Tara. Patrick determined to make his way to the hill of Slane, the loftiest elevation in the country, overlooking the vast plain of Meath. Here he followed a traditional Christian custom of lighting a Passover fire on Easter Eve—a custom which was nearly universally practiced at that time.

The fire was immediately seen at Tara where the king of Ireland, Laoghaire, was meeting with the chiefs of Ireland. According to tradition, no fires were to be lit on this night until the King lit his fire at Tara. When seeing Patrick’s fire, the King and his priests rush to Slane to punish the offender and there found Patrick. But upon the arrival of the King and his priests, Patrick was allegedly enabled to demonstrate the miraculous power of the living God to the King. As a result, the paganism of the Druids lost credibility with the King and was defeated. As a result of Patrick’s supernatural display, many, including Laoghaire himself, were baptized into the Christian faith.

IX. Rivalry with Druidism

A. Religion of Magic

One of the greatest challenges Patrick faced was the pagan religion of Druidism. Indeed, prior to Patrick’s ministry in Ireland, the Irish worshiped “nothing but idols and impure things.”[19] The religion of the Irish was almost pure magic, and was led by Druid priests. The Drui or Druid priest was a combination of a philosopher and a wizard. For centuries the Druids were all-powerful, not only in Ireland, but also in England and Gaul. Though pagan in origin, several Druid practices continued among Christian nations. Among them were the winding of the Maypole, the use of holly at Christmas, the custom of kissing beneath the mistletoe, and knocking on wood to avert evil.

B. Druids Originate Halloween Practices

Many of your Halloween practices have come from the Druids. The Druids and Celtic people observed two sacred festivals a year. The first took place at the beginning of the month of May and was called Beltane or “fire of god.” During this festival, a large fire was kindled on an elevated spot to honor the sun after the gloom of winter. The second festival was observed the first of November, called Hallow-eve. This occasion was used for the sake of adjudicating crimes against persons or property. Associated with these judicial acts was the practice of relighting fires, which had previously been scrupulously extinguished, from one central fire.

C. Origin of “Eeny, meeny, miny, mo”

The children's "counting-out rhyme," "Eeny, meeny, miny, mo," is a version of the Druid death chant, "Eena, mena, mona, my." It was used by the Druids to select victims to be ferried across the Menai Strait and burned alive in wicker cages as human sacrifices in the Beltane spring festival on the sacred Isle of Mona (now Anglesey).

D. Infant Sacrifice

Patrick vigorously opposed the sacrificing of infants to harvest gods. Like Patrick and generations of Christians who preceded the life and ministry of Patrick, Christians in the present generation are likewise called upon by God to defend the unborn and weak. Christians are presently being called upon to save the lives of the unborn and redeem their cultures from the paganism which ostensibly gains more and more vitality daily.

E. Treatment of Prisoners of War

The Irish were fierce warriors. Patrick also vigorously opposed long established practices relating to prisoners of war. Prisoners were often sacrificed and their skulls used as ceremonial drinking bowls. Today in many colleges and universities, “intelligent” professors ridicule missionaries for having "Christianized" pagan cultures around the world. Judge for yourself. Would it have more civilized, more humane for Christians to have neglected ethical concerns? The struggle between Christianity and paganism (in this case the form of Druidism) had begun many years before Patrick arrived in Ireland as missionary, and it continues many centuries following.

F. Treatment of Women

It was common for Patrick to invite unmarried women to become the brides of Christ by joining a “nunnery.” In this way, it was believed that women could serve the interests of the Church more effectively. Those women who became Christians and who were slaves of a pagan lord were in “constant threats and daily terror” because they, as Christians, resisted the advances of their owners.[20] In this way, the status of women in Ireland was elevated. In fact, wherever the Gospel of Christ has been preached, the well-being of children and women has always been elevated.

In 461, Patrick passed from this life. Tradition suggests his body was placed upon a wagon to which were harnessed two young unbroken bullocks which were allowed to wonder about. Where they stopped, at Dun-Lethglaisse (now known as Downpatrick), there Patrick was buried.[21] Later, a church was built above his grave, and like many Christian leaders, he was venerated and worshiped by other Christians—something which Jesus Christ never intended for his servants.

I. Immediate Influence

A. Number of Baptisms

Patrick spent more than thirty years in Ireland, evangelizing and baptizing many thousands.[22] Though Patrick made no attempt to accurately record the number of individuals he baptized, some of his biographers have suggested he baptized nearly one hundred thousand.

B. Churches started

During his ministry, it is believed Patrick started some two hundred churches, and to care for these churches, he ordained pastors “for them everywhere, to care for this people freshly brought alive in their faith.”[23]

C. Monasteries

The children of the kings and nobility of the Irish were “proud to be counted monks and virgins of Christ.”[24] As a result of such well-trained individuals entering the ranks of monasteries and convents, Irish monasticism was successful in keeping alive education during a very dark period of European history.

II. Into the Fifth and Sixth Centuries

A. Irish monks

Patrick’s Irish successors emerged as one of the most vital missionary and educational movements in all history. In the fifth and sixth centuries, uncivilized German people called barbarians swept through the Roman Empire, destroying centers of learning and education. Because of this, many call this period the Dark Ages, when civilization seemed poised for extinction. During this time, Irish Christians preserved many of the classical and Christian authors. But, for Irish monks, the Scriptures became a special object of scholarly study.

B. St. Briget (Brigid) of Kildare

Among the many thousands who came to Christ under Patrick’s ministry in Ireland, there emerged two very important figures. The first was a young woman by the name of Briget (born about 450 or 453). Briget was a dairymaid on a farm, and through her beauty, attracted many suitors seeking her hand in marriage, but Briget chose rather to be a “bride of Christ.” She delighted herself in giving away much of her father's fortune to the poor. She founded a church and missionary school at Kildare and traveled widely, spreading the gospel wherever she went.

C. St. Columba of the Isle of Iona

The second person who continued Patrick’s Christian ministry was Columba. Columba established churches throughout Ireland and engaged in a missionary tour to Scotland with his twelve disciples when he was only forty-two. Armagh was a center of Patrick’s ministry as Kildare had been the center of Briget’s evangelistic efforts. But for Columba, the Isle of Iona became the center of his great missionary endeavors. He scaled the hills of Scotland, founding churches and monasteries alike. His influence upon the Scottish people was so great that kings and nobles for centuries were buried at the center of Columba's missionary endeavors—the Island of Iona.

One of the greatest Columba's greatest contributions to the cause of Christ was his literary endeavors. He wrote hymns and poems, but even more important was his efforts to spread the Bible. About 1445, Johann Gutenberg (1400-1468) invented the printing press, and the first book printed on the new movable-type press was the Bible (1456). But nearly a thousand years earlier, Columba was distributing the Word of God. Columba is believed to have copied nearly three hundred copies of the Bible himself. He passed from this life while making a copying one of the Psalms.

I. Influence of Book of Armagh

Many unfortunate things have taken place in the name of Jesus Christ. This is no less true in the politics of the church as well. Within two centuries of Patrick’s death, the city of Armagh in the county of Ulster made a special claim for itself. The other city to claim a place of importance for itself because of his ministry there was Downpatrick, which was also in the county of Ulster. The city of Armagh attempted to become the most dominant center in all of Ireland, and the method used to grant itself this distinguished position was to assert a claim of a special relationship to Patrick.

In the ninth century, two books were inserted into the Book of Armagh which argued for the priority of Armagh over Downpatrick. The book was written by Muirchu and Tirechan. In it, Muirchu depicted Patrick as confronting the king of Ireland, Laoghaire of the Ui Neill at Tara; but this was a devise of Muirchu to find favor with the descendants of the Ui Neill who still held power at Tara. Muirchu’s objective was to strengthen Armagh’s claim of superiority over Downpatrick.

II. Influence of Normans

When the Normans arrived in Ireland in the late twelfth century, John De Courcy, after arriving in Downpatrick, alleged to have found the body of Patrick and reburied him on Cathedral Hill. By showing such interest in Patrick, De Courcy hoped to endear himself to the Irish, thereby reducing the chance of revolt by the Irish. He also claimed to have found the bodies of St. Colmcille and St. Bridget, reburying them beside Patrick.

After this, De Courcy’s wife brought some Cistercian monks from Furness in Northumbria to Inch and built an abbey for them there. One of the monks, Jocelyn, wrote a biography of Patrick, linking his supernatural powers with the Normans. In doing so, he hoped to discourage the local populace from revolting against their new Norman overlords.

On March 17th, remember Patrick not as the one who drove the snakes out of Ireland. Rather, remember Patrick for who he truly was—a missionary who spread the saving Gospel of Jesus Christ throughout Ireland. The preceding pages represent only a fraction of the much larger heritage which Christians should celebrate. Through years of ministry among the Irish, Patrick kept the Christian faith. Will you?

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Skinner, Confession of St. Patrick, 79-81.

[2] Saint Patrick Centre, “How the Myth of Saint Patrick Developed: The Controversy,” http://www.saintpatrickcentre.com/pages/myth.html, March 13, 2003.

[3] Saint Patrick Centre, “How the Myth of Saint Patrick Developed: The Controversy,” http://www.saintpatrickcentre.com/pages/myth.html, March 13, 2003.

[4] He was probably born in Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton in Scotland. In his Confession, Patrick indicates his parents residence was at Bannavem Taburniae, but the location cannot be identified.

[5] The site of this town is unknown today.

[6] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 49.

[7] John Skinner, trans., The Confession of St. Patrick and Letter to Coroticus (New York: Image Books, Doubleday, 1998), viii.

[8] Skinner, Confession, 38-39.

[9] Very likely the southeast coast.

[10] Where he landed cannot be determined. It is very likely that it was Britain.

[11] There is a gap in Patrick’s Confession from his experience with the sailors to his return to his parents. The exact length of time between these two events is not known, though it does not seem they are too far removed from each other.

[12] It seems evident that Patrick did not go to Gaul at this time. In his confession, he writes, “So now, having been away for these few years [six years in captivity], He was once more back in Britain” (p. 45).

[13] Some biographies mention that Patrick spent some time in a monastery in Europe and even traveled to Rome. However, there is no historical evidence to support this. Patrick never mentions this in any of his writings.

[14] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 62.

[15] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 55.

[16] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 57.

[17] A highly celebrated eighth and ninth century vellum codex which contains some of the most important documents of the history of Ireland, some of which are in Irish, others are in Latin. Of special interest are the two lives of St. Patrick and St. Martin of Tours by Sulpicius Severus.

[18] Saint Patrick Centre, “How the Myth of Saint Patrick Developed: The Controversy,” http://www.saintpatrickcentre.com/pages/myth.html, March 13, 2003.

[19] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 60.

[20] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 62.

[21] St. Patrick’s actual burial site is unknown though it is believed to be at Downpatrick. In the Book of Armagh, Muirchu suggests these reluctant oxen stopped by chance at Downpatrick. In writing this story, Muirchu was attempting elevate the importance of Armagh in the life of the Irish church over all other possible contenders for dominance of Irish Christianity. Saint Patrick Centre, “How the Myth of Saint Patrick Developed: The Controversy,” http://www.saintpatrickcentre.com/pages/myth.html, March 13, 2003.

[22] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 68.

[23] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 57.

[24] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 61.

[25] Skinner, Confession of St. Patrick, 79-81.