Morality More Important Than the Constitution

In 2012, distinguished Yale Law School professor Akhil Reed Amar[1] published his book, America's Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By.[2] Summarizing his book Amar said, "Despite its venerated place atop American law and politics, our written Constitution does not enumerate all of the rules and rights, principles and procedures that actually govern modern America." Suggesting that interpretation of the Constitution "cannot be understood in textual isolation," Amar insists that jurisprudence must have the right to "particularly privileged sources of inspiration and guidance, including the Federalist papers, William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream” speech.'" While the former sources of interpretation remain legitimate sources of interpretation, conservatives have a right to reject the latter two.Morality More Important Than the Constitution

To Amar's discredit he seeks to carve out a place of prominence for Justice Hugo Black, arguably one of the worst justices to be placed on the Supreme Court. Hiding behind the false claim of "textualism," Amar cannot defend the incongruent decisions of Black in light of the history of judicial opinions.Morality More Important Than the Constitution

Like so many others in legal studies, Amar and Black introduce novel ideas of interpretation of America's organic legal documents. Lamentably, Amar and Black (and many of their colleagues in legal studies) have resolutely overlooked and even rejected what America's Founding Fathers believed was far more important to the longevity of the nation they birthed. In fact, from the end of the nineteenth century down to the present, American legal studies have increasingly rejected what the Founding Fathers believed was more fundamental to the well-being of America than the Constitution itself. And what did the Founding Fathers believe was more important to the success of America than the Constitution? Christian morality!

This article is one we have featured in our newsletters. To subscribe and receive our newsletters, please click the link: Signup...

Article Contents

The definition of several terms are important to the subject at hand. In contemporary American culture the term "religion" is generally employed in reference to all religions of the world. However, with regard to early America, the term "religion" was generally a reference to any Christian denomination. As the primary author of the first state constitution of Massachusetts, John Adams observed that "religion" produced "the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government" and in the same article, defined religion as "Protestant" .[3] While Mr. Adams specifies "religion" as "Protestant," Founding Fathers generally use the term "religion" to apply to Christians in general—though Protestantism was the prevailing influence, as is discussed in the lines that follow.[4]

The term "ethics" is often used to describe personal standards of what is regarded as right and wrong but was not frequently employed by the Founding Fathers. Two terms used by the Founders to describe the collective opinions of right and wrong were "morality" (morals) and "virtue" and were often used interchangeably. Noah Webster, who exercised a profound influence upon the development of "American English, "defined" moral" in his 1841 Dictionary as "Relating to the practice, manners, or conduct of men as social beings in relation to each other, and with reference to right and wrong."[5]

Morality Foundational to Good Government

Throughout the twentieth century and early twenty-first century, Marxist and secular authors have minimized or eliminated the priority that American Founders placed upon morality. The Founders believed that Christian morality was the bedrock upon which the Constitution (or any good form of government) was erected. A few quotes should demonstrate this priority.

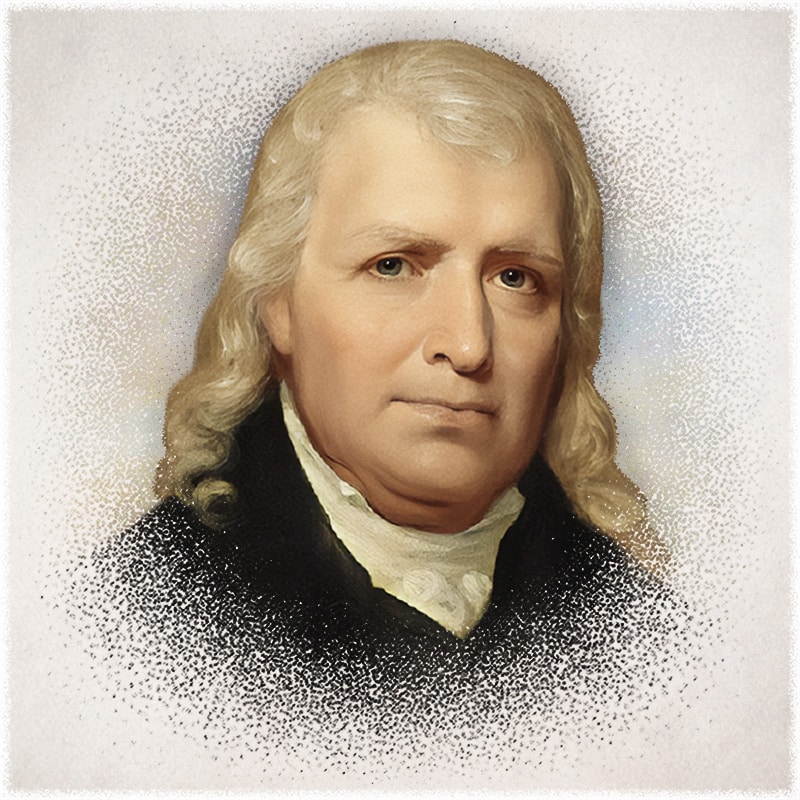

George Washington

George Washington is among a half-dozen Founding Fathers who are often falsely charged as deists.[6] Responding to the charge that her father, George Washington, was not a Christian, adopted daughter Nelly Parke Custis stated, "I should have thoughtit the greatest heresy to doubt his firm belief in Christianity. His life, his writings prove that he was a Christian."[7] In his Farewell Address to the nation as he was leaving the presidency, he wrote:

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked, where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle. It is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule indeed extends withmore or less force to every species of free government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?[8]

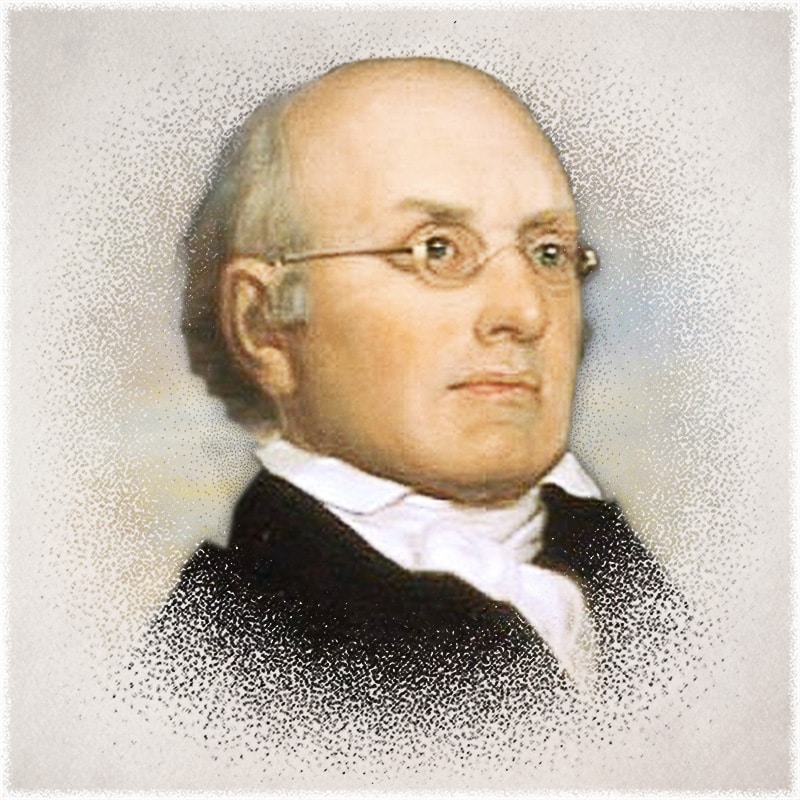

Dr. Benjamin Rush

Dr. Benjamin Rush, along with George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, was one of three of the most important Founding Fathers.[9] Concerning the priority of Christian morality in government, Dr. Rush wrote…

In contemplating the political institutions of the United States, I lament that we waste so much time and money in punishing crimes and take so little pains to prevent them.We profess to be republicans and yet we neglect the only means of establishing and perpetuating our republican forms of government; that is the universal education of our youth in the principles of Christianity by means of the Bible; for this divine book, above all others, favors that equality among mankind, that respect for just laws, and all those sober and frugal virtues which constitute the soul of republicanism.[10]

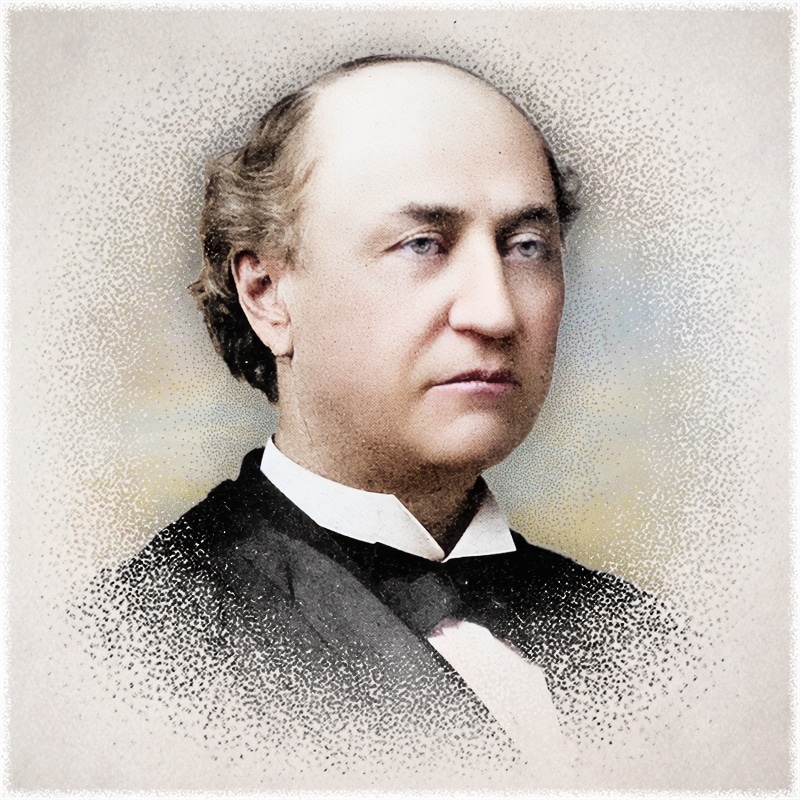

Dr. Benjamin Franklin

Though Benjamin Franklin was not an orthodox Christian he was not a Deist as alleged by many.[11] On his deathbed Franklin called upon long-time Methodist friend Rebecca Grace, who led him to saving faith in Jesus Christ.[12] In the early 1790s Mr. Franklin wrote to Thomas Paine concerning his Age of Reason:

By the argument it contains against a particular Providence, though you allow a general Providence, you strike at the foundations of all religion.... But were you to succeed, do you imagine any good would be done by it? You, yourself, may find it easy to live a virtuous life without the assistance afforded by religion; you, having a clear perception of the advantages of virtue and the disadvantages of vice, and possessing a strength of resolution sufficient to enable you to resist common temptations. But think how great a portion of mankind consists of weak and ignorant men and women, and of inexperienced, inconsiderate youth of both sexes who have need of the motives of religion to restrain them from vice, to support their virtue, and retain them in the practice of it till it becomes habitual, which is the great point for its security. And perhaps you are indebted to her originally, that is to your religious education, for the habits of virtue upon which you now justly value yourself. I would advise you, therefore, not to attempt unchaining the tiger, but to burn this piece before it is seen by any other person... If men are so wicked with religion, what would they be if without it.[13]

Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams is remembered as the "Father of the American Revolution" and was a deeply dedicated Christian. That he believed Christian morality was fundamental to the success of the Constitution is apparent in the following quote:

The sum of all is if we would most truly enjoy this gift of Heaven, let us become a virtuous people: then shall we both deserve and enjoy it. While, on the other hand, if we are universally vicious and debauched in our manners, though the form of our Constitution carries the face of the most exalted freedom, we shall in reality be the most abject slaves.[14]

Unlike contemporary thinkers who hesitate to raise the issue of morality, this was a frequent subject for the Founding Fathers.[15] That they believed Christianity should sustain the moral life of the nation is easily establish by the historical record. While an extended treatment of this subject is well beyond the scope of this article, thumbnail sketches of some of the most important evidence should be sufficient to satisfy the most candid reader.

The thirteen American English colonies were established by charters granted from 1606 to 1732.[16] While it is true that a number of the colonies were granted charters of settlement for commercial reasons, they did not neglect the observance of the Christian Faith. In 1606 King James I granted the First Virginia Charter to the Virginia Companies of Plymouth and London. The Christian ethos of the charter that established the first permanent English settlement in the New World was evident:

We, greatly commending and graciously accepting of their [the Virginia Companies of Virginia and London]desires for the furtherance of so noble a work which may, by the Providence of Almighty God, hereafter tend to the glory of his divine majesty in propagating of Christian religion to such People as yet live in darkness and miserable Ignorance of the true knowledge and worship of God and may, in time, bring the infidels and savages living in those parts to human civility, and to a settled and quiet government: Do, by these our letters patents, graciously accept of, and agree to, their humble and well-intended desires...[17]

As English colonists ventured to the New World, more charters were granted which reflected a Christian moral ethos.

The myth that America's Founding Fathers were Deists has been told so frequently that a vast number of contemporary Christians have come to believe it. The fact is, there was no discontinuity between the character of the colonies and the states that followed the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Example after example could be shown to prove this fact, but given the fact that Benjamin Franklin is often charged with being a Deist, his participation in the formation of Pennsylvania's first Constitution speaks volumes to the one willing to be instructed by historical evidence. Nearly three months after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Pennsylvania ratified its first state constitution on September 28, 1776. The following is representative of the Christian influence in other state constitutions:

And each member, before he takes his seat [in the state Assembly], shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz: I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration.[18]

The state took seriously the advancement of religion…

Sect. 45. Laws for the encouragement of virtue and prevention of vice and immorality shall be made and constantly kept in force, and provision shall be made for their due execution: And all religious societies or bodies of men heretofore united or incorporated for the advancement of religion or learning, or for other pious and charitable purposes, shall be encouraged and protected in the enjoyment of the privileges, immunities and estates which they were accustomed to enjoy, or could of right have enjoyed, under the laws and former constitution of this state.[19]

And who was the chairman of the state convention?

Passed in Convention the 28th day of September 1776, and signed by their order.

BENJ. FRANKLIN, Prest.[20]

Such statements concerning Christianity as the foundation of virtue and morality in other state constitutions were often more explicit! In the mid-nineteenth century, Congress memorialized America's Christian moral foundation.

Far more details of the ways Congress has advocated Christian morality could be exhibited,[21] but a survey of several important facts should demonstrate to the candid reader there was no discontinuity between the Christian influence of the colonial era and the national era that arose with the War of Independence.

First Continental Congress

On October 20, 1774, the First Continental Congress (September 5, 1774—October 26, 1774) ratified the Continental Association, also known as the Articles of Association or simply the Association. The Articles of Association were addressed to the King and "British ministry" and contained fourteen resolutions that called upon all American colonies to avoid trade with Great Britain or Ireland. These resolutions were intended to force British officials to reverse their policies which Americans believed were "calculated for enslaving these colonies." The prohibition of all trade was ordered to take effect on December 1, 1774. To enforce the dictates of the Articles, local committees of safety increasingly functioned as colonial governments[22] as the authority of British officials diminished or dissolved completely. Without reservation delegates to the First Continental Congress collectively identified themselves as members of the “Protestant religion, ”[23] “Protestant Christians, ”[24] “free Protestant colonies, ”[25] “Protestant brethren, ”[26] and “free Protestant English settlements.”[27]

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (May 10, 1775—March 1, 1781) and Congress of the Confederation (March 1, 1781—March 3, 1789) were no less willing to embrace the Christian morality which was an integral part of the advent of the Thirteen Colonies. One proof of this fact (among many) is the proclamations of spiritual acts of fasting, prayer, and thanksgiving. From June 12, 1775, to August 3, 1784, Congress issued sixteen spiritual proclamations, often asking the states to invite their citizens to cease physical labor to engage in fasting, prayer, and thanksgiving.[28] The first of the sixteen proclamations provides insight to their content:

This Congress, therefore, considering the present critical, alarming and calamitous state of these colonies, do earnestly recommend that Thursday, the 20th day of July next, be observed by the inhabitants of all the English colonies on this continent as a day of public humiliation, fasting, and prayer; that we may, with united hearts and voices unfeignedly confess and deplore our many sins; and offer up our joint supplications to the all-wise, omnipotent, and merciful Disposer of all events; humbly beseeching him to forgive our iniquities, to remove our present calamities, to avert those desolating judgments with which we are threatened… That virtue and true religion may revive and flourish throughout our land; and that all America may soon behold a gracious interposition of Heaven for the redress of her many grievances, the restoration of her invaded rights, a reconciliation with the parent state on terms constitutional and honorable to both; and that her civil and religious privileges may be secured to the latest posterity.

As the proclamation concluded, Congress asked that all unnecessary work cease on the day of observance:

And it is recommended to Christians of all denominations to assemble for public worship, and to abstain from servile labor and recreations on said day.[29]

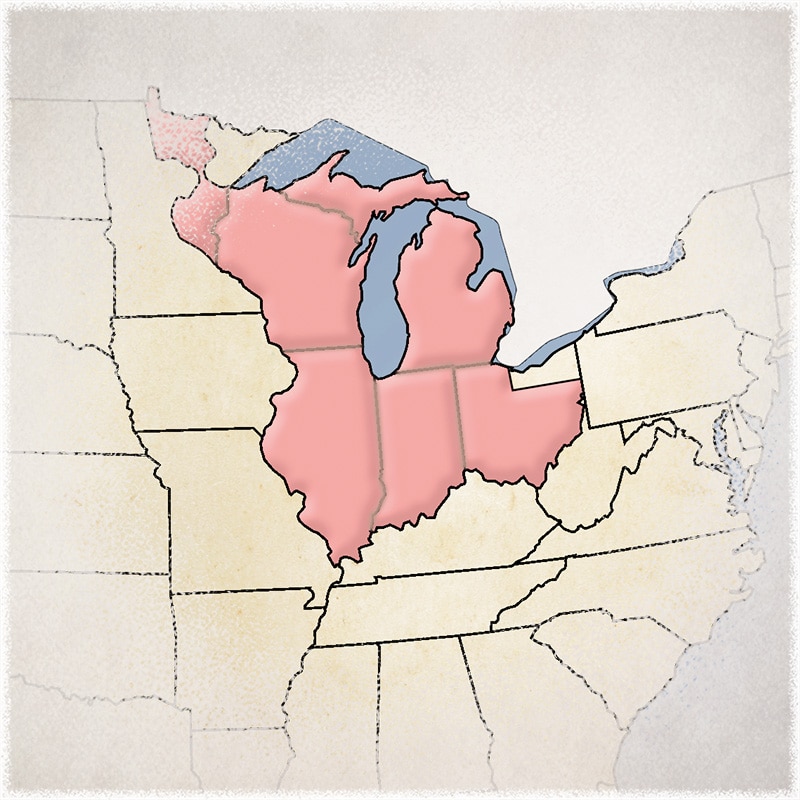

1787—The Northwest Ordinance

America recognizes four organic laws which no other state of federal law may usurp. They include the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Articles of Association (1777), the Northwest Ordinance (1787), and the Constitution (1789). Though originally this ordinance was intended to govern the expectations for statehood for the territory northwest of the Ohio River, the Northwest Ordinance "eventually served in related forms in the establishment of thirty-two states, one commonwealth, and one republic." [30] Readers will observe that the third article of the Northwest Ordinance passed at the "federal" level of Congress in both 1787 and again under the Constitution in 1789 required that "religion" be taught:

Article the Third. Religion, morality and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, Schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.[31]

Careful readers will notice that Founding Fathers believed that morality was founded upon "religion" or Christianity, and knowledge arose out of the influence of morality.

1853—Senate Committee on the Judiciary

In 1852, a request was laid before Congress to defund chaplains in Congress and the military. Senator George E. Badger from the State of North Carolina, reported for the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on January 21, 1853:

...we are a Christian people—from the fact that almost our entire population belong to or sympathize with some one of the Christian denominations which compose the Christian world. And Christians will, of course, select for the performance of religious services, one who professes the faith of Christ…. We are Christians, not because the law demands it, not to gain exclusive benefits or to avoid legal disabilities, but from choice and education; and in a land thus universally Christian, what is to be expected, what desired, but that we shall pay a due regard to Christianity and have a reasonable respect for its ministers and religious solemnities?[32]

1854—House Committee on the Judiciary

More than a year after the Senate responded to the request of 1852 to defund chaplains, the Committee of the Judiciary of the House of Representatives replied. Chairman of the House Committee on the Judiciary James Meacham, submitted the findings of his committee on March 27, 1854, writing:

At the adoption of theconstitution we believe every State—certainly ten of the thirteen—provided as regularly for the support of the church as for the support of the government: one, Virginia, had the system of tithes. Down to the Revolution, every colony did sustain religion in some form. It was deemed peculiarly proper that the religion of liberty should be upheld by a free people. Had the people during the Revolution had a suspicion of any attempt to war against Christianity, that Revolution would have been strangled in its cradle. At the time of the adoption of the constitution and the amendments, the universal sentiment was that Christianity should be encouraged—not any one sect. Any attempt to level and discard all religion would have been viewed with universal indignation.[33]

Not only did the legislative branch of the federal government affirm Christianity's moral influence upon the origin of America, but the judiciary made similar affirmations. Many state and federal court cases speak in harmony concerning this truth.[34] While considerable evidence could be referenced to demonstrate this truth, summaries of several federal decisions should satisfy the sincere student of American history.

1799—US Court of Appeal

In 1796, President Washington appointed Samuel Chase to the Supreme Court. At the time, Supreme Court justices also served on district courts of appeal. Serving as Supreme Court Justice on the Maryland Court of Appeal, Chase wrote the unanimous opinion in Runkel v. Winemiller, October term 1799, in which he wrote:

Religion is of general and public concern and on its support depends, in great measure, the peace and good order of government, the safety and happiness of the people. By our form of government, the Christian religion is the established religion; and all sects and denominations of Christians are placed upon the same equal footing and are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty. The principles of the Christian religion cannot be diffused and its doctrines generally propagated without places of public worship, and teachers and ministers to explain the Scriptures to the people and to enforce an observance of the precepts of religion by their preaching and living.[35]

1844—America a "Christian Country"

In the landmark United States Supreme Court case (January term 1844), Vidal v. Girard's Executors, Justice Joseph Story rendered the unanimous decision, twice identifying America as a "Christian Country" :[36]

Why may not the Bible, and especially the New Testament, be read and taught as a divine revelation in the schools? Its general precepts expounded, and its glorious principles of morality inculcated?… Are not these truths all taught by Christianity, although it teaches much more? Where can the purest principles of morality be learned so clearly or so perfectly as from the New Testament? Where are benevolence, the love of truth, sobriety, and industry, so powerfully and irresistibly inculcated as in the sacred volume?[37]

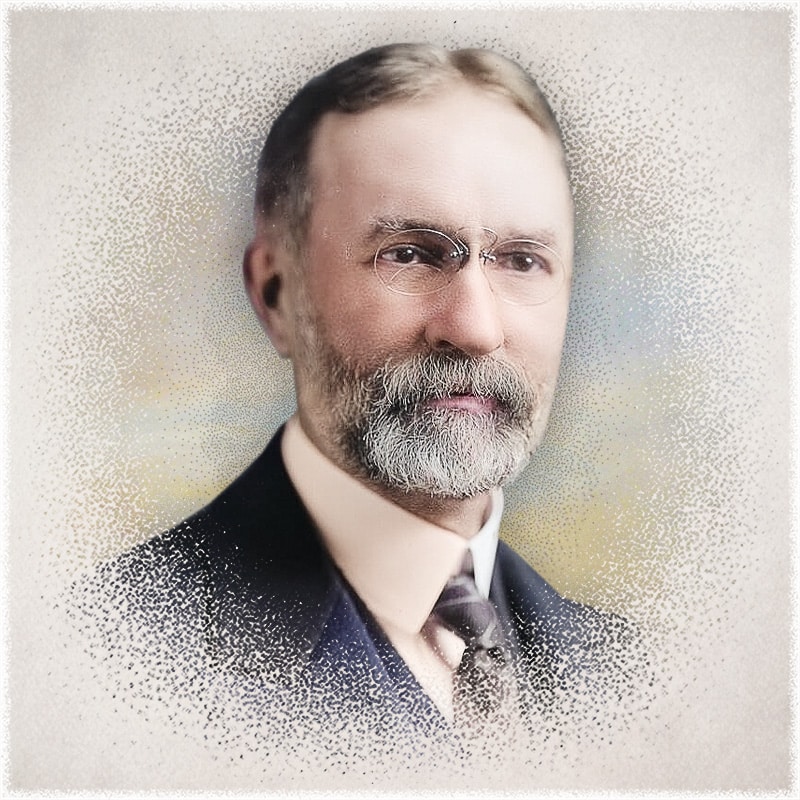

1892—America a "Christian Nation"

On February 29, 1892, Justice David Brewer rendered the unanimous decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Holy Trinity v. The United States. In his decision, Justice Brewer referenced more than eighty pieces of evidence to support the opinion of the Court. One sentence sufficiently encapsulates the finding of all justices:

These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.[38]

1931—America a "Christian People"

In 1931, Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland delivered the majority opinion in United States v. Macintosh. Making reference to the 1892 decision of Justice Brewer, Sutherland referred to America as "a Christian people" :

We are a Christian people (Holy Trinity Church v. United States, 143 U. S. 457, 470-471), according to one another the equal right of religious freedom, and acknowledging with reverence the duty of obedience to the will of God.

To these affirmations from the federal court could be added others, as well as many from state courts.

Conclusion: Morality Matters More

Hugo Black went out of his way to eliminate Christian expressions from public life. His secular legacy—as well as the Akhil Amar’s—have patterned their courts and classrooms, not after a more perfect union, but rather have created a climate of greater instability and insolvency of American government. By failing to impeach such rogue state and federal judges, state assemblies and Congress itself have participated in setting aside what the Founding Fathers believed was more important than the Constitution!

Contrary to the opinions of Black, Amar, and many like them, America's Founding Fathers knew that recipes matter, and for this reason advocated for a Christian moral foundation for the Constitution. On October 1, 1798, President John Adams penned a letter to the Massachusetts Militia. In it, he alluded to the devastation of the French Revolution which was the result of Voltaire and atheism and contrasted it with the care of Providence in America. Mr. Adams observed the inability of the Constitution to govern an immoral people:

…we have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge, or gallantry would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.[40]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Akhil Reed Amar: Sterling Professor of Law." Yale Law School. Last modified Accessed March 14, 2023.https://law.yale.edu/akhil-reed-amar.

Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. 34 vols., edited by Division Of Manuscripts Edited From The Original Records In The Library Of Congress By Worthington Chauncey Ford Chief. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937.

The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the State, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America. Edited by Francis Newton Thorpe. 7 vols., edited by Francis Newton Thorpe. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909.

Warren-Adams Letters: Being Chiefly a Correspondence among John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Warren. 2 vols. [Boston]: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917-1925.

Major Acts of Congress. 3 vols., edited by Brian K. Landsberg. New York: Thomson Gale, 2004.

"The First Charter of Virginia; April 10, 1606." The Avalon Project: Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. Last modified Accessed July 6, 2015. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/va01.asp.

Reports of the Senate, 32 Cong. 2 sess. Rep. Com. No. 376. Vol. 671. pt. 1, January 21, 1853.

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1972.

Amar, Akhil Reed. America's Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By. New York: Basic Books, 2012.

Asbury, Francis. Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury. 3 vols., edited by Elmer T. Clark, J. Manning Potts, and Jacob S. Payton. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1958.

Barton, David and Tim Barton. The American Story: The Beginnings. Edited by Second. Aledo, TX: WallBuilder Press, 2021.

Breen, T. H. American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

Brewer, David and The United States Supreme Court. U.S. Reports: Holy Trinity Church V. United States, 143 U.S. 457. 1891.

Chase, Samuel. Runkel V. Winemiller, 4 H. and Mch. 429 (Court of Appeals of Maryland, 1799).

Dreisbach, Daniel L. and Mark David Hall. Faith and the Founders of the American Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Flick, Stephen A. When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God. Clinton, Tennessee: Christian Heritage Fellowship, Inc., 2017.

Franklin, Benjamin. The Works of Benjamin Franklin: Containing Several Political and Historical Tracts Not Included in Any Former Edition and Many Letters Official and Private, Not Hitherto Published: With Notes and a Life of the Author. Edited by Jared Sparks. 10 vols. Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company, 1836-1840.

Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin with Notes and a Sketch of Franklin's Life from the Point Where the Autobiography Ends, Drawn Chiefly from His Letters. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888.

Morris, Benjamin. Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Developed in the Official and Historical Annals of the Republic. Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864.

Rush, Benjamin. "A Defense of the Use of the Bible as a Schoolbook, Addressed to the Rev. Jeremy Belknap, of Boston." In Essays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical by Benjamin Rush, M.D. And Professor of the Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Practice in the University of Pennsylvania, 93-113. Philadelphia: Thomas and Samuel Bradford, 1798.

Sparks, Jared. The Writings of George Washington; Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original Manuscripts; with a Life of the Author, Notes, and Illustrations. 12 vols. Boston: Little, Brown, 1858.

Story, Joseph and The United States Supreme Court. U.S. Reports: Vidal Et Al. V. Girard's Executors, 43 U.S. 2 How 127.

Sutherland, George and The United States Supreme Court. U.S. Reports: United States V. Macintosh, 283 U.S. 605. 1930.

United States Congress, House. Chaplains in Congress and in the Army and Navy. House Report 124, 33rd Congress, 1st session, March 27, 1854.

Washington, George. Washington’s Farewell Address to the People of the United States. edited by 106th Congress Senate Document No. 106-21, 2d Session. Washington: Congress, 1998.

Webster, Noah. An American Dictionary of the English Language Exhibiting the Origin, Orthography, Pronunciation, and Definitions of Words. New York: White and Sheffield, 1841.

Wells, William V. The Life and Public Service of Samuel Adams, Being a Narrative of His Acts and Opinions, and of His Agency in Producing and Forwarding the American Revolution. 3 vols. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865.

[1] "Akhil Reed Amar: Sterling Professor of Law, "Yale Law School, March 14, 2023; https://law.yale.edu/akhil-reed-amar.

[2] Akhil Reed Amar, America's Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By (New York: Basic Books, 2012).

[3] The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the State, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America, ed. Francis Newton Thorpe, 7 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), 3:1889-90.

[4] A definitive study in America's religious heritage is Dr. Sydney E. Ahlstrom's book, A Religious History of the American People, which earned Dr. Ahlstrom the National Book Award in category Philosophy and Religion in 1973. Ahlstrom was a Yale University professor and a specialist in the religious history of the United States. Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1972), 17.

[5] Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language Exhibiting the Origin, Orthography, Pronunciation, and Definitions of Words (New York: White and Sheffield, 1841), s.v. "Moral" .

[6] Daniel L. Dreisbach and Mark David Hall, Faith and the Founders of the American Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 13.

[7] Jared Sparks, The Writings of George Washington; Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original Manuscripts; with a Life of the Author, Notes, and Illustrations, 12 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1858), 12:406.

[8] George Washington, Washington’s Farewell Address to the People of the United States (Washington: Congress, 1998), 20.

[9] John Sanderson, Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence (Philadelphia: R.W. Pomeroy, 1823), 4:285.

[10] Benjamin Rush, "A Defense of the Use of the Bible as a Schoolbook, Addressed to the Rev. Jeremy Belknap, of Boston," inEssays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical by Benjamin Rush, M.D. And Professor of the Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Practice in the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Thomas and Samuel Bradford, 1798), 112-13.

[11] Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin with Notes and a Sketch of Franklin's Life from the Point Where the Autobiography Ends, Drawn Chiefly from His Letters (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888), 77-79.

[12] Francis Asbury, Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, 3 vols. (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1958), 1:187.

[13] Date uncertain.Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin: Containing Several Political and Historical Tracts Not Included in Any Former Edition and Many Letters Official and Private, Not Hitherto Published: With Notes and a Life of the Author, ed. Jared Sparks, 10 vols. (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company, 1836-1840), 10:281-82.

[14] William V. Wells, The Life and Public Service of Samuel Adams, Being a Narrative of His Acts and Opinions, and of His Agency in Producing and Forwarding the American Revolution, 3 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865), 1:22-23.

[15] A brief survey of "morality" in the Warren-Adams Letters will demonstrate this fact. See Warren-Adams Letters: Being Chiefly a Correspondence among John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Warren, 2 vols. ([Boston]: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917-1925).

[16] Virginia (1606), Massachusetts Bay (1620), New Hampshire (1629), North Carolina (1629) South Carolina (1629), Maryland (1632), Connecticut (1636), Rhode Island (1636), Delaware (1664), New York (1664), New Jersey (1664), Pennsylvania (1681), Georgia (1732)

[17] "The First Charter of Virginia; April 10, 1606, "The Avalon Project: Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, July 6, 2015; http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/va01.asp.

[18] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 5:3085.

[19] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 5:3091.

[20] Constitutions, Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 5:3092.

[21] See the time-honored work on the broad influence of America's Christian origin, Benjamin Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Developed in the Official and Historical Annals of the Republic (Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864).

[22] T. H. Breen, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 261.

[23] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 1:35.

[24] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:35.

[25] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:76, 88.

[26] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:100.

[27] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:117.

[28] Stephen A. Flick, When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God (Clinton, Tennessee: Christian Heritage Fellowship, Inc., 2017).

[29] Journals of the Continental Congress, 87-88.

[30] Major Acts of Congress, 3 vols. (New York: Thomson Gale, 2004), 3:85-86.

[31] Journals of the Continental Congress, 32:340-341.

[32] RepReports of the Senate, 32 Cong., 2 sess., Rep. Com. No. 376, Vol. 671, pt. 1 (January 21, 1853), 3.

[33] House United States Congress, Chaplains in Congress and in the Army and Navy (House Report 124, 33rd Congress, 1st session, March 27, 1854), 6. The entire report is contained in pages 1-10.

[34] David Barton and Tim Barton, The American Story: The Beginnings, ed. Second (Aledo, TX: WallBuilder Press, 2021), 261-64.

[35] Samuel Chase, Runkel V. Winemiller, 4 H. and Mch. 429 (Court of Appeals of Maryland, 1799), https://cite.case.law/h-mch/4/429/.

[36] Joseph Story and The United States Supreme Court, U.S. Reports: Vidal Et Al. V. Girard's Executors, 43 U.S. 2 How 127, 173, 198, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/43/127/.

[37] Unanimous decision was rendered by Justice Joseph Story in January term 1844. Story and Court, U.S. Reports: Vidal Et Al. V. Girard's Executors, 43 U.S. 2 How 127, 200.

[38] David Brewer and The United States Supreme Court, U.S. Reports: Holy Trinity Church V. United States, 143 U.S. 457. 1891, 471, https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep143457/.

[39] George Sutherland and The United States Supreme Court, U.S. Reports: United States V. Macintosh, 283 U.S. 605. 1930, 625, https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep283605/.

[40] John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, with a Life of the Author, Notes and Illustrations by His Grandson, Charles Francis Adams, 10 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1851-1856), 9:228-29.