June 12, 1775: First Congressional Fasting and Prayer Proclamation

Before adjourning the First Continental Congress on October 26, 1774, representatives stipulated that if the grievances that existed between the Thirteen American Colonies and Great Britain were not settled, a Second Continental Congress should be convened "on the tenth day of May next."[1] Contrary to their hopes and prayers, hostilities only increased between the two parties. Less than a month earlier, on April 19, 1775, the first military engagements of the American Revolution were waged at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. As proposed, the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775—with only twelve of the Thirteen Colonies sending representatives.First Congressional Prayer and Fasting Proclamation

Article ContentsFirst Congressional Prayer and Fasting Proclamation

John Hancock Becomes President of Congress

The third president of Congress was Peyton Randolph, who had served as the First President of Congress the previous year.[2] As in the case of the First Continental Congress, Mr. Randolph was called away from this office by extenuating personal circumstances, having only served from May 10 to May 23, 1775. By unanimous consent of Congress, John Hancock was chosen to succeed Randolph to the presidency, serving his first term in that office from May 24 to October 31, 1777.[3] Like Randolph, Hancock also served a second term as President of Congress from November 23, 1785 to June 5, 1786.

Americans have remembered John Hancock as the first signer of the Declaration of Independence—a right duly reserved for him as President of Congress. However, secular attempts to remove the awareness of America's Christian origin have successfully removed a little-known fact about this wealthy patriot. John Hancock was the son and grandson of Christian ministers.[4] Given this little-known biographical fact, it is entirely appropriate that the son and grandson of Christian ministers should be the first to sign a congressional request to all the Colonies represented in Congress calling for a day of fasting and prayer. Less than three weeks after assuming the presidency of Congress, John Hancock was the first to sign such a proclamation.

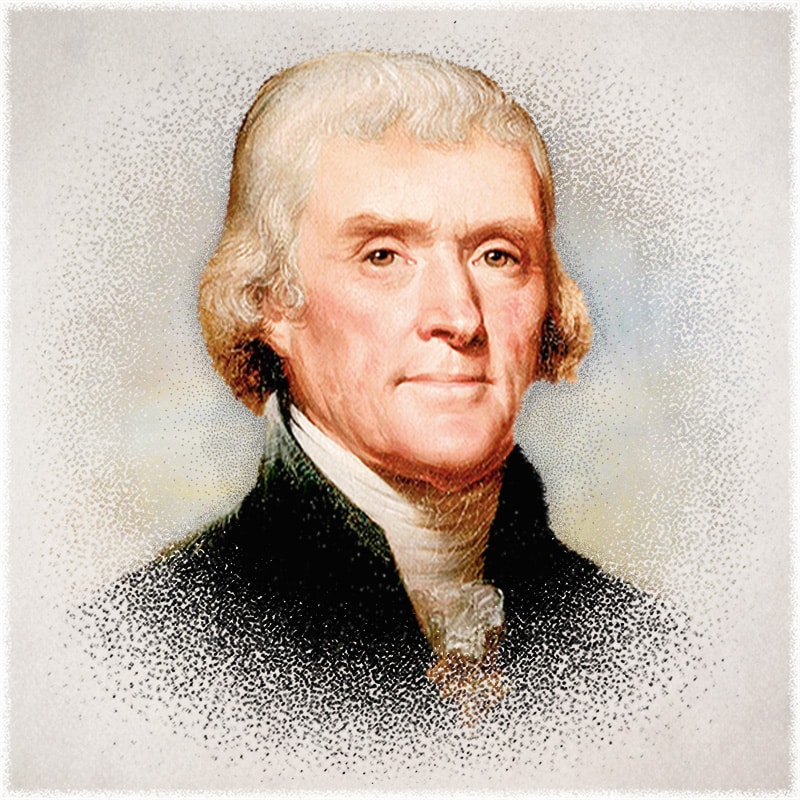

Both fasting and thanksgiving days had been observed in New England since the beginning of the seventeenth century, but of the two types of spiritual observances, it was fasting days that were first imported to the Southern Colonies. What will surprise most secularists is the fact that it was Thomas Jefferson who helped introduce the practice to Virginia. Jefferson recorded that he, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and several other members of the Virginia House of Burgesses "were under conviction of the necessity of arousing our people from the lethargy into which they had fallen as to passing events; and thought that the appointment of a day of general fasting and prayer would be most likely to call up and alarm their attention." The House of Burgesses appointed June 1, 1774 that year as a day of fasting and prayer, which Jefferson noted was received as a "shock of electricity."[5] Among the first in the South—prior to Congress' decision to establish a day of prayer—the provincial congress of South Carolina established February 17, 1775 as a day of fasting and prayer. Maryland set aside May 11 and Georgia followed appointing a day in July of the same year.[6]

Committee Composes First Proclamation

In the first spiritual proclamation of Congress calling for "a day of humiliation, fasting and prayer," only twelve colonies are referenced in the Journals of Congress. Twelve of the Thirteen Colonies were represented by delegates when the Second Continental Congress began. Georgia had failed to send any representatives to the First Continental Congress, and did not initially send any delegates to the Second, though Dr. Lyman Hall was sent from the parish of St. John's, Georgia.[7] Two months after the Second Continental Congress began, the Georgia Provincial Congress consented to send delegates; having arrived, they presented their credentials and assumed their seats among the other delegates on July 20.[8] But, more than an month prior to the arrival of the delegates from Georgia, representatives from the other twelve Colonies had proposed that a three-member committee compose a proclamation for "a day of humiliation, fasting and prayer. The Journals of the Continental Congress records the selection of the committee and the task with which it was charged:

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 7, 1775:

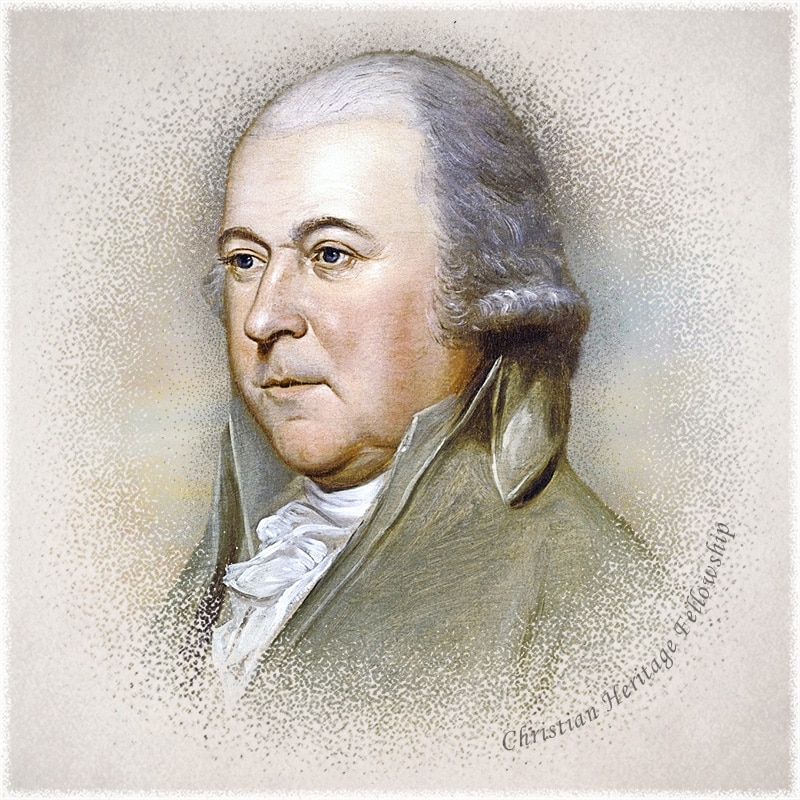

"On motion, Resolved, That Thursday the 20th of July next, be observed throughout the twelve United Colonies, as a day of humiliation, fasting and prayer: and that Mr.[William]Hooper, Mr. J[ohn]Adams, and Mr.[Robert Treat]Paine, be a committee to bring in a resolve for that purpose."[9]

Less than a week passed until the committee had prepared and presented their proclamation to the Congress as a whole. Congress was preparing the Colonies for war in the decisions it was making, but it was not indifferent to spiritual matters—a fact that is evident in the proclamation that was adopted:

MONDAY, JUNE 12, 1775

The committee, appointed for preparing a resolve for a fast, brought in a report, which, being read, was agreed to as follows:

As the great Governor of the World, by his supreme and universal Providence, not only conducts the course of nature[10] with unerring wisdom and rectitude, but frequently influences the minds of men to serve the wise and gracious purposes of his providential government; and it being, at all times, our indispensable duty devoutly to acknowledge his superintending providence,[11] especially in times of impending danger and public calamity, to reverence and adore his immutable justice as well as to implore his merciful interposition for our deliverance:

This Congress, therefore, considering the present critical, alarming and calamitous state of these colonies, do earnestly recommend that Thursday, the 20th day of July next, be observed, by the inhabitants of all the English colonies on this continent, as a day of public humiliation, fasting and prayer; that we may, with united hearts and voices, unfeignedly confess and deplore our many sins; and offer up our joint supplications to the all-wise, omnipotent, and merciful Disposer of all events; humbly beseeching him to forgive our iniquities, to remove our present calamities, to avert those desolating judgments, with which we are threatened, and to bless our rightful sovereign, King George the third, and[to]inspire him with wisdom to discern and pursue the true interest of all his subjects, that a speedy end may be put to the civil discord between Great Britain and the American colonies, without farther effusion of blood: And that the British nation may be influenced to regard the things that belong to her peace, before they are hid from her eyes: That these colonies may be ever under the care and protection of a kind Providence, and be prospered in all their interests; That the divine blessing may descend and rest upon all our civil rulers, and upon the representatives of the people, in their several assemblies and conventions, that they may be directed to wise and effectual measures for preserving the union, and securing the just rights and privileges of the colonies; That virtue and true religion may revive and flourish throughout our land; And that all America may soon behold a gracious interposition of Heaven, for the redress of her many grievances, the restoration of her invaded rights, a reconciliation with the parent state, on terms constitutional and honorable to both; And that her civil and religious privileges may be secured to the latest posterity.

And it is recommended to Christians, of all denominations, to assemble for public worship, and to abstain from servile labour and recreations on said day.

Ordered, That a copy of the above be signed by the president and attested by the Secy and published in the newspapers, and in hand bills.[12]

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

No index entries found.

[1] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1:102.

[2] Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:12.

[3] Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:58-59.

[4] Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "Hancock, John."

[5] Derek Davis, Religion and the Continental Congress, 1774-1789: Contributions to Original Intent (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 84.

[6] Davis, Religion and the Continental Congress, 84.

[7] The St. John's parish sent a representative of its own. The records of Congress for May 13, 1775 note his arrival: "The Congress being informed that Doctr. Lyman Hall attended at the door, as a delegate from the parish of St. John's in the colony of Georgia, and desired to know whether, as such, he may be admitted to this Congress; Agreed unanimously, That he be admitted as a delegate from the parish of St. John's, in the colony of Georgia..." Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:44.

[8] Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:192-193.

[9] Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:81.

[10] Emphasis added.

[11] Emphasis added. Congress makes it clear that irreligion or secularism was intolerable to human government. Delegates believed it was the duty of human government to acknowledge divine government.

[12] Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:87-88.