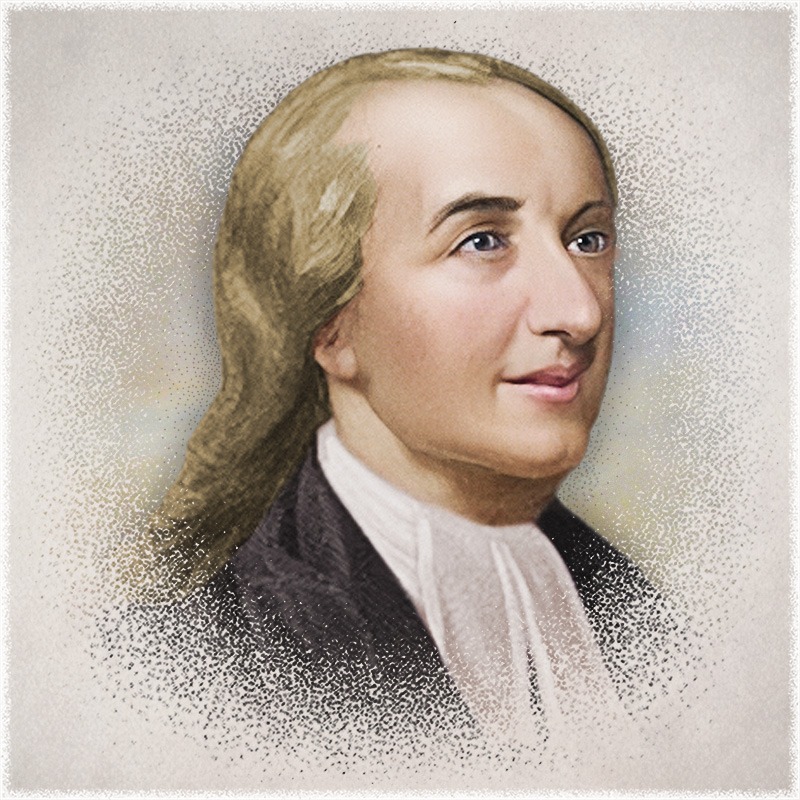

John William Fletcher on Prayer

One of the most remarkable ministers in English history, and in all the history of the Christian Church, was an Anglican priest by the name of John William Fletcher (1729-1785), "First Theologian of Methodism." Fletcher was a close companion with John and Charles Wesley and had been hand picked by Wesley to succeed himself as leader of British Methodism, but Fletcher died before John Wesley.The following excerpt is taken from an unpublished work titled, "John William Fletcher, Vicar Of Madeley: A Pastoral Theology."

The priesthood of all believers encompasses the vital task of intercessory prayer. Christ's sacrifice is the foundation through which intercession is made to the Father. Both the unbeliever[1] and the believer[2] are recipients of the complementary intercession of the Son and Spirit. By virtue of their participation in Christ, all believers become intercessors[3] and join in the "holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ."[4] But for Fletcher, the place of prayer in the life of the pastor is one of great importance. Of the importance of prayer to the pastor's ministry, he wrote in his Portrait of St. Paul:

. . . the true minister divides his time between the two important and refreshing occupations of preaching and prayer; by the former, making a public offer of Divine grace to his hearers and by the latter, soliciting for them in secret the experience of that grace. . . .

Pastors who pray thus for their flocks, pray not in vain. Their fervent petitions are heard; sinners are converted, the faithful are edified, and thanksgiving is shortly joined to supplication.[5]

Prayer is "at once an important duty" and the "grand instrumental means by which the soul is kept alive."[6] In his unpublished sermon, "The Christian's Weapon, 'All Prayer,'" Fletcher introduced "several kinds of prayer which the Christian solider may use to his advantage."[7] Here he listed four types of prayer which the true believer is bound by moral duty to use: private, family, social, and mental prayer. These four types of prayer provide a very helpful outline of Fletcher's own life of prayer.[8]

His biographers universally attested to the unusual degree of communion which he enjoyed with God in "mental prayer." Upon meeting the Methodists in London in the fall of 1753, Fletcher's already scrupulous character and spiritual discipline is significantly altered. Before his conversion in January 1754, prayer was a part of his legalistic, spiritual discipline to save himself.[9] But following his conversion, the purpose of his prayer and spiritual discipline changed, though the nature of his practice remained much the same.[10] His nearly ascetic practices extended throughout his life, not as practices to gain God's favor,[11] but as opportunities to enjoy fellowship with God more deeply[12] and to make himself of greater service to Christ.[13]

Before accepting the vicarage of Madeley, he earnestly cultivated close communion with God. Each Sunday Fletcher attended the Atcham parish church while still a tutor to the Hills, but at the close of the service, instead of going home in the coach with the family, he usually took a walk along the Severn River where he enjoyed some time in meditation and prayer. One of the Hills' servants, Mr. Vaughan, recalled those occasions when he had the opportunity to join Fletcher:

It was our ordinary custom when the Church Service was over, to retire into the most lonely fields or meadows where we frequently either kneeled down, or prostrated ourselves upon the ground. At those happy seasons I was a witness of such pleadings and wrestlings with God, such exercises of faith and love, as I have not known in any one ever since.[14]

One of the ways in which his communion with God affected him and the character of his ministry is through a deep sense of the eternal. This trait is not only characteristic of Fletcher, but also of a number of the earnest, Anglican evangelicals of the eighteenth century. Elliott-Binns notes, "They were men for whom life and existence had a seriousness and significance which seems lacking today. They saw all things in light of eternity . . ."[15] His spiritual discipline, of which prayer is such a vital part, is a means whereby he prepared himself for greater, more zealous temporal ministry by constantly gazing upon the eternal. His communion with God cultivated an alertness to the brevity of life and an awareness of the nearness of eternity. Good friend Joshua Gilpin wrote, "Through every period of his religious life he appeared as a pilgrim and stranger in the world, unallured by its smiles, unmoved by it frowns, and uninterested in its changes."[16] Mary Fletcher said that he always "walked with death in sight."[17]

His personal discipline enhanced his communion with God and influence with others. His own moral character, which he believed so important to the Christian pastor,[18] is shaped, in part, in prayer. Fletcher is a man of strong passion and in his younger years particularly prone to anger. Sensitive to this flaw in his character, he "has frequently thrown himself on the floor and laid there most of the night bathed in tears, imposing victory over his own spirit." In time he does obtain victory; so much so that, "For twenty years and upwards before his death, no one ever . . . [saw] him out of temper, or . . . [heard] him utter a rash expression on any provocation whatever."[19] It was his aspiration to conform all of his life to the image of Christ, and to this end he maintained close communion with God. Of this ambition, Mary wrote,

. . . so far as I can say, It was his constant application to maintain an uninterrupted sense of the divine presence; in order to which, he was slow of speech, and had the greatest government of his words. He acted, he spoke, he thought as under the immediate eye of God: and thus setting God always before him . . .[20]

Private prayer was a frequent privilege for Fletcher as well. Here he wrestled before God to attain the grace necessary to live a godly life and faithfully perform his ministry. From the beginning of his ministry in Madeley, he was deeply sensitive of his need of divine grace to assist him in his care of souls. From December 1776 to May 1777, he stayed at the home of his close friend, Charles Greenwood, Stoke-Newington seeking to recover his health after the extensive Minute Controversy. During this time he related a vignette of his early ministry to a member of the Greenwood family:

About the time of my entering into the ministry I, one evening, wandered into a wood musing on the importance of the office I was going to undertake. I then began to pour out my soul in prayer; when such a sense of the justice of God fell upon me, and such a sense of his displeasure at sin, as absorbed all my powers and filled my soul with the agony of prayer for poor, lost sinners. I continued therein till the dawn of day; and I considered this as designed of God to impress upon me more deeply those solemn words: 'Therefore knowing the terrors of the Lord, we persuade men.'[21]

He remained deeply conscious of his own need of grace to faithfully perform his ministry and remained equally alert to the role that prayer plays in receiving that grace. His good friend, Henry Venn, who is privileged with the opportunity of visiting with Fletcher at Madeley, noted Fletcher's dependence upon prayer to execute his ministry: "Dear Mr. Fletcher had such a sense of the weight of his office that, like his Saviour, he could continue in prayer in the woods, all night long; and, like Him, lie prostrate on the ground pleading for grace to fulfill His ministry."[22]

The spiritual, moral, and social[23] interests of his parishioners weighed heavily upon him throughout his incumbency. From the demands of the parish, he frequently withdrew to his sacred retreats in prayer where he invited God to accompany his public labors. Gilpin, having had the privilege of living with Fletcher before he himself was ordained, notes that he frequently retired to his study in private prayer:

His deepest and most sensible communications with God were enjoyed in those hours when the door of his closet was shut against human creatures, as well as human cares. And though he rejoiced to lift up his hands in company with his friends, yet when his heart was at any time peculiarly inflamed with desire, or pressed with affliction, he would say to his friends, as Christ to his disciples, "Sit ye here while I go and pray yonder." His closet was the favorite retirement to which he constantly retreated whenever his public duties allowed him a season of leisure. . . . In all cases of difficulty he would retire to this consecrated place to ask counsel of the Most High; and here, in times of uncommon distress, he has continued during whole nights in prayer before God.[24]

Here, in his study, "the wall of his chamber could exhibit a proof of his vehement intercession; that part of it against which he was accustomed to kneel, appearing deeply stained with the breath he had spent in fervent supplication."[25]

In January of 1782, Fletcher brought his wife Mary to Madeley for the first time. Here she remained until her death on December 9, 1815, thirty years after Fletcher's death. She quickly few as in love with the parishioners of Madeley, but she also deeply loved her husband whom she frequently found expending his physical energy upon the interests of the parish. Fletcher's already frail condition was exacerbated by his prayer life, which only increased Mary's concern for him:

Another uncommon talent which God had given him was a peculiar sensibility of spirit. He had a temper the most feeling of any I ever knew. Hardly a night passed over but some part of it was spent in groans for the souls and bodies committed to his care. I dreaded his hearing either of the sins or sufferings of any of his people before the time of his going to bed, knowing how strong the impressions would be on his mind, chasing the sleep from his eyes.[26]

Mary was sensitive to her husband's intense love for his parish, and though concerned for his health, she is careful not to interrupt his habit of prayer.[27] She was, in a large measure, responsible for enabling him to minister as effectively as he did in his closing years, the duty and privilege of prayer being one of the many ways in which she supported him. Frequently, she gladly accepted his invitations to join with him in prayer for the parish. Together they bore the interests of the parish before God in intercessory prayer:

For some time before his last illness, his precious soul (always alive to God) was particularly penetrated with the nearness of eternity; there was scarce an hour in which he was not calling upon me to drop every thought and every care, that we might attend to nothing but drinking deeper into God. We spent much time in wrestling prayer for the fullness of the Spirit and were led, in a very peculiar manner, to a total surrender of ourselves to God, to do or suffer whatever was pleasing to him.[28]

Fletcher's social prayer life was a combination of Anglican liturgy[29] and Methodist extemporary prayer.[30] The formal prayers of the Prayer Book were a natural part of the liturgy and his lectures.[31] As early as 1758, he can be found reading prayers from the Prayer Book at Methodist chapels[32] in London. And his sermon case, used during his incumbency at Madeley, contained the prayers which Fletcher very likely used before and after preaching.[33] As an Anglican priest, he did not shy away from using the "well designed form of prayer" so deeply despised by Abiah Darby.[34]

Whether visiting in the home of a parishioner,[35] assisting in manual labor,[36] or greeting and conversing with a friend,[37] everything was done with prayer and praise.[38] Gilpin took special note of his public extemporary prayers:

In his social prayers he paid but little attention to those rules which have been laid down with respect to the composition and order of these devotional exercises. As the Spirit gave him utterance, so he made his requests known unto God. But, while he prayed "with the Spirit," he prayed "with the understanding also." His words flowed spontaneously and without any premeditation, yet always wonderfully adapted to the occasion. Nothing impertinent, artificial, or superfluous appeared in his addresses to the Deity: and while he presented those addresses, there was a solemnity and animation in his manner which tended, not only to edify, but to quicken and exalt the soul.[39]

His ready disposition to pray can be seen in the last Methodist Conference which he attended. In late July 1784, the Fletchers attended the Methodist Conference at Leeds. This Conference initially proved to be very divisive between John Wesley and his preachers. A great deal of resentment on the part of many of the preachers arose over Wesley's Deed of Declaration. This document placed legal control of British Methodism under the authority of one hundred preachers whom Wesley had personally chosen to succeed him. The tension sprung from the fact that many of the preachers were excluded from the legal proceedings of the emerging church. To help resolve the conflict, Fletcher assumed a mediating posture between Wesley and his preachers. His efforts are recorded by one of the itinerants, Charles Atmore, who also attended the Conference:

Never, never, while memory holds her seat, shall I forget with what ardour and earnestness Mr. Fletcher expostulated, even on his knees, both with Mr. Wesley and the Preachers. To the former he said, 'My father! my father! they have offended, but they are your children.' To the latter he exclaimed, 'My brethren! my brethren! he is your father!' and then, portraying the work in which they were unitedly engaged, fell again on his knees, and with much fervour and devotion, engaged in prayer. The Conference was bathed in tears; many sobbed aloud.[40]

This unusual spectacle on the final day of the Conference dissolved the tensions between Wesley and his preachers.[41] But what is not discernible from this account is Fletcher's prayer which preceded his successful mediation. Prior to the final day of Conference, Fletcher privately groaned under the burden which the controversy had inflicted upon the proceedings of the Conference. Mary writes of this experience:

When we were at Leeds in the year 1784, I had another proof of the tender sensibility of his heart. O how he was affected concerning the welfare of the Conference! When little disputes arose between some of the brethren, his inmost soul groaned under the burden; and by 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning I was sure to hear him breathing out prayer for the peace and prosperity of Zion: and when I have observed to him I feared it would hurt his health, and wished him to sleep more; he would answer, 'O Mary! the cause of God lies near my heart.[42]

What may have happened had John Fletcher not been at the Conference at such a critical juncture in Methodist history one can only speculate. What appeared more certain is that Fletcher's life of intercessory prayer, both on the Conference floor and in private, played a decisive role.[43]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Oden writes, "Christ intercedes not only for those most responsive to grace, but for sinners, following the pattern of the suffering Servant who 'made intercession for the transgressors' (Isa. 53:12). Christ's intercession is for all sincere penitents (typified by the unmeritorious thief in Luke 23:24). Christ intercedes for all humanity, yet it is said that those who do not believe do not enjoy the effect of his intercession." Word of Life, 2:310.

[2] "Christ intercedes especially for the church, for 'those you have given me' (John 17:9, 24). He intercedes not only for the immature in faith that they may be brought fully to repentance and faith (Luke 13:8), but also for the believers that they may be kept deeply rooted in faith (John 17:8-11). He intercedes for those in union with the community of faith (John 17:21) and in union with Christ himself (John 17:13-18), that they might be made holy (John 17:19)." Ibid., 2:310.

[3] The Apostle Paul writes to Timothy, "I urge then, first of all, that requests, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for everyoneÑfor kings and all those in authority." 1 Tim. 2:1-2a, NIV.

[4] 1 Peter 2:5, NIV.

[5] Works, 3:30. Scott aptly recognized Fletcher's aspiration to be a man of prayer when he wrote, "If he excelled in one religious duty more than another, it was in prayer." Abraham Scott, "A Biographical Sketch of the Author [John Fletcher]," in The Works of the Rev. John Fletcher with a Life by the Rev. Abraham Scott, new edition (London: Printed for Thomas Allman, 1840), 1:xvi.

[6] Sermon notes, SCRO, 2280/16/51. Success in the ministry, to a large degree, does not depend upon humanly devised methods but divinely appointed means: "The more sterile the soil appears, which he is called to cultivate, the more he waters it, both with his tears and with sweat of his brow . . ." Works, 3:75.

[7] Ibid., 2280/16/51.

[8] Mary indicated that Fletcher provided no formal account of his personal prayer life. Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 33.

[9] In his letter to Charles Wesley in May of 1757, Fletcher wrote of his moralistic efforts to save himself after arriving in England: "By this time I was a strict Legalist. I spent part of the day in reading the Scriptures and in prayer thinking that my repenting, added to these duties, would screen me from the wrath to come." Letter to Charles Wesley (May 10, 1757), PWHS 33 (June 1961): 28.

Fletcher deprived himself of needed food and sleep in his quest for salvation; an effort which he regreted later in life. See Benson, Life of John W. De La Flechere, 32.

[10] Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 20-21. Fletcher's diet soon after his conversion consisted entirely of vegetables; for a period of nearly six months he lived entirely on bread with milk and water. It also was his habit to sit up two nights a week for reading, prayer, and meditation. See M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 13; Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 7:439. Lockhart believed that Fletcher's deep sense of humility was cultivated by his ascetic practices. Lockhart, "John William de la FlŽch�re," 105.

Some of his ascetic practices are reflected under his "Rules for a Holy Life" in his "Commonplace Book." He wrote, "Mortify five senses till crucified with ChristÑhave a continual eye inwardly to thy soulÑSit at Christ's feet; cast away thine own will; consult his at every word, morsel, and motion; ask his leave even in lawful actionsÑReckon all as dung and dross compared to the union of thy soul with God." "Commonplace Book," 179-80.

[11] Writing against the Calvinists in his Last Check, he made a necessary distinction between the "lawful" and "sinful" desires of the flesh: "We should properly distinguish between the lawful and the sinful lusts or desires of the flesh. To desire to eat, to drink, to sleep, to marry, to rest, to shun pain at proper times and in a proper manner, is no sin; such lusts or desires are not contrary to the law of liberty. . . ."

". . . What the apostle has chiefly in view [in Gal. 5:24] through the whole, is to reprove the Galatians for their carnality in following Judaizing teachers and in bearing the fruits of the flesh, envy, variance, &c, insomuch that they were ready to bite and devour one another." Works, 2:530-31.

The forgoing statement helped to correct the common notion that Fletcher believed ascetic practices are a means of purging the corrupt nature from a believer. George May is of this group who made this erroneous assumption of Fletcher: "This asceticism was a strong feature of early Evangelicalism. In these days when the ordinary 'Evangelical' would look upon fasting or any stern self-discipline as superstitious, or at least wholly unnecessary, it is startling to find Fletcher thus disciplining himself, or William Wilberforce, somewhat later, following almost exactly the same course of stern fasting and asceticism in many ways. To men of this stamp, human nature was too corrupt to be dealt with by easy methods; the knife must be laid at the very root of bodily desires and indulgence. Fletcher of Madeley." Theology: A Monthly Journal of Historic Christianity 1, no. 1 (July 1920): 18-28), 20.

[12] Lockhart, John Fletcher, 10.

[13] Personal discipline was important to Fletcher to render the minister more useful in the spread of the gospel: "A pastor must, sooner or later, convert sinners if he sincerely and earnestly calls them to repentance toward God, and faith in our Lord Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, though filled with indignation against sin, with compassion toward the impenitent, and with gratitude to Christ, he should, like St. Paul, in proportion to his strength, wrestle with God by prayer, with sinners by exhortation, and with the flesh by abstinence; . . ." Works, 3:72.

[14] Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 11:288.

[15] Elliott-Binns, Early Evangelicals, 15. Fletcher's spiritual appetite was in excess of his physical appetite. Lawton notes Fletcher's ascetic characteristic when he writes, "He dropped his clay long before he died, so translucent was his spirit." Shropshire Saint, 8.

[16] Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 147. Of Fletcher's disinterest in temporal passions, Gilpin further writes, "In all the changing circumstances of life, he looked and acted like a man whose treasure was laid up in heaven." Ibid., 21.

[17] Moore, Life of Mary Fletcher, 164.

[18] The first part of his Portrait considers the pastor's moral character. It was a very important issue to him and will be considered in the ensuing chapter.

[19] Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 11:345.

[20] M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 33. The fact that Fletcher was sensitive to the guidance of the Spirit in his ministry is reflected in his conversations. John Wesley wrote in his biography of Fletcher, ". . . so intensely was his mind fixed upon God that I have heard him say, 'I would not move from my seat without lifting up my heart to God.'" Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 11:290.

[21] Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 11: 306-307.

[22] Venn, Vicar of Huddersfield, 548.

[23] As will be noted in the last chapter, Fletcher faced stiff opposition from some of his parishionersÑparticularly the first few years of his ministry in Madeley. In his Portrait of St. Paul, he encouraged fellow pastors to prevail in prayer through those periods of great trial: "Far from being discouraged by the trials which befall him, the true minister is disposed in such circumstances to pray with the greater fervency; and according to the ardour and constancy of his prayers, such are the degrees of fortitude and patience to which he attains." Works, 3:68.

[24] Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 62. He warned against "publicly uttering long and passionate prayers produced with the most violent efforts," and encouraged "ardent prayers, in humble faith." Works, 3: 187, 193.

[25] Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 63. Sturdee recorded his tour of the vicarage years later: "From the bedroom we proceeded to the study, 'just as Fletcher left it, save for necessary repair,' observed the Vicar. A smallÑvery small roomÑlighted only by one window, darkened by heavy framework and small panes of glass. There on the left side of the fire-place was the corner where Fletcher knelt until the very wall bore traces of his breath as he poured out his soul in supplication." Sturdee, "Mecca of Methodism," 8.

[26] Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 11:348. In dealing with a daughter of a local farmer who was suicidal, Fletcher resorted to prayer and fasting when his resources in dealing with the situation are greatly taxed. For more than two years he wrestles with this problem. Finally in July of 1763, he wrote to Charles Wesley for the third time concerning the matter: "The young person I mentioned as being sorely tempted by the devil, is happily delivered." Works, 4:320. Also see Seymour, Countess of Huntingdon, 1:240-41; Fletcher, Posthumous Pieces, 104-105; Fletcher, Works 4:318-19.

Just as Fletcher faithfully prayed for his parishioners, he also invited them to pray for their pastor. In his unpublished sermon, "The Apostle's Request," he solicited the prayers of his people on behalf of the ministers of the gospel, knowing that "the enemy will endeavour to destroy them." Sermon notes, SCRO, 2280/16/10.

Fletcher's intercession in the interest of others extended far beyond his parishioners and the concerns of the parish. He is passionately concerned for family members in Switzerland and for his friends. And for persecuted believers whom he never met, he fasted, wept, prayed, and made "continual intercession before the great Lord of the vineyard." Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 103, 109.

[27] Mary was not completely passive toward Fletcher's extraordinary efforts in prayer, but she did not become intrusive. As will be seen, she expressed her concerns to Fletcher that his prayer life threatened his health. See M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 30.

[28] M. Fletcher, Account of the Death of Rev. Fletcher, 4. For the Anglican evangelicals of the eighteenth century, family prayer is an important part of Christian discipline. Davies, Worship and Theology in England, 219-20.

[29] It is unclear whether Fletcher held morning and evening prayer in Madeley. From what little may be gathered from Gilpin, it appeared that he did have morning and evening prayers, but whether they were held according to the rubric of the Prayer Book cannot be determined. Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 121.

[30] Davies indicated that the extemporary prayer of the Methodists was a trait which is shared with dissent. Worship and Theology in England, 190.

[31] Lawton indicated that the Bidding Prayer prescribed by Canon fifty-five, which is required to be used by all preachers before sermons, lectures, and homilies, is placed in Fletcher's sermon case. Shropshire Saint, 24. His use of collects at his society in Madeley Wood, suggested that he may have made wider use of the Prayer Book and its prayers than previously realized. See Tyerman, Wesley's Designated Successor, 77.

[32] Works, 4:312.

[33] The prayers are in part drawn from the Prayer Book and combined with Methodist freedom of expression. Frank Baker "John Fletcher's Sermon Notes," Proceedings of Wesley Historical Society 28, part 2 (June, 1951): 31.

[34] Fletcher, "Letter to Mrs. Darby," 76.

[35] Of his pastoral visits, Gilpin wrote: "In those houses where the sons and daughters of peace were found, he was welcomed as a messenger of the most joyful tidings and honored as an ambassador of Jesus Christ. These happy families submitted with joy to his paternal authority and considered his pastoral visits as an invaluable privilege. They looked upon their houses as consecrated by his prayers and received his benedictions with reverence and gratitude." Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 51-52.

[36] In 1785, Fletcher and his parishioners at Coalbrookdale began the construction of a chapel for his society in the Dale. Before its completion he bowed to pray; one of his parishioners who was present on the occasion bore witness to Fletcher's intercession on behalf of his parishioners: ". . . this very excellent minister, who was mighty in prayer, 'bowed his knees before the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ': when he prayed for the workmen and for all those who may enter therein, that 'they may be brought to the knowledge of the truth and be saved.' Those effectual fervent prayers have availed for me and many others of my dear Christian friends . . ." "Wesleyan Methodists in Coalbrookdale to 1836," TD, 1839, Madeley Parish Records, Shropshire County Record Office, Shropshire, England, 2280/16/186, 1.

[37] Thomas Rankin had the opportunity to visit with Fletcher after the latter had returned from the continent in 1781. Rankin's conversation with Fletcher provided deeper insights into the role which prayer played in Fletcher's life. Knowing Rankin had labored five years in America, Fletcher inquired concerning "the work of God": "I gave him, as far as I was capable, a full account of everything that he wished to know. While I was giving him this relation, he stopped me six times, and . . . poured out his soul to God for the prosperity of the work, and our brethren there. He appeared to be as deeply interested in behalf of our suffering friends as if they had been his own flock at Madeley. He several times called upon me, also, to commend them to God in prayer." Benson, Life of John W. De La Flechere, 264-65.

[38] M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 33-34.

[39] Portrait of Saint Paul (Gilpin notes), 61-62. Mary recorded one of Fletcher's adages concerning public prayer: "When many believing hearts are lifted up and wrestle in prayer together, we may compare them to many hands which work a large pump; at such times particularly, the fountains of the great deep are broken up, the windows of heaven are opened, and rivers of living water flow from the hearts of obedient believers." Moore, Life of Mary Fletcher, 74.

[40] John S. Stamp, "Memoir of the Rev. Charles Atmore, Compiled from Various Documents," Wesleyan Methodist Magazine 4th ser., 1 (January 1845): 14-15.

[41] Wesley briefly summarized the proceedings of the Conference in his Journal: "Tuesday, 27. Our Conference began; at which four of our brethren after long debate, (in which Mr. Fletcher took much pains) acknowledged their fault, and all that was past was forgotten." Wesley, Works (3d ed.), 4:285. See Tyerman, Wesley's Designated Successor, 546; Richard Treffry, Memoirs of the Rev. Joseph Benson (London: Published by John Mason, 1840), 113-14.

[42] M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 30.

[43] When in prayer, it is revealed to him that he will not live to attend the Conference of 1785: "A little before his last illness, being on his knees in prayer for light whether he should go to London or not; the answer seemed to himÑ'No, not to London, but to your grave.' Acquainting me [Mary] with this, he said with a heavenly smile, 'Satan would represent it before me as something awful, enforcing these wordsÑ"the cold grave, the cold grave."'" True to the impression he receiveed in prayer, he did not live to attend the 1785 Conference. M. Fletcher, Letter to Mons. H. L. De la Flechere, 28.