Flag Day — A Christian Contribution to America

In the United States, Flag Day is observed on June 14, which commemorates the adoption of the flag of the United States by a resolution of the Second Continental Congress on Saturday, June 14, 1777. Observance of this annual event, however, did not receive prominence for many years after the approval of the resolution of the Continental Congress. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation that established June 14 as America's official Flag Day. Not until August 1949, however, did Congress move to establish a National Flag Day through official act.Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to AmericaFlag Day

In contemporary America, Christians must look beyond superficial popular presentations recounting national holidays and history to discern the influence Christianity has had upon the conception and construction of America. By considering a series of developments related to the use of the American flag, Christians will arrive at a deeper appreciation for the overwhelming influence that their faith has wielded in the development of America.Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to AmericaFlag Day

Article Contents

The first and most important development concerning the American flag is the origin of the flag itself. Like so many other subjects concerning American history, the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have dealt harshly with details of national origin that once were very settled and unquestioned. Following an approach to the study of American history that started as early as the 1920s, many American "historians" have attacked the most prominent figures and features in American history and cast doubt and denial upon the historical records concerning them. Often, the motivating force has been a secular or irreligious worldview that refuses to acknowledge the positive influences of Christianity. This irreligious worldview has not limited itself to the consideration of American studies alone, but has also cast its contrived version of the world upon biblical and theological studies and nearly every other subject or discipline. It is similar to the historical efforts of conquering armies to rewrite the histories of the nations they conquered, attempting to remove important events and national heroes and heroines from the memory of those they conquered. Though America and the Christian Church have not been conquered militarily, they have seen their histories and accounts of their heroes rewritten by their enemies!

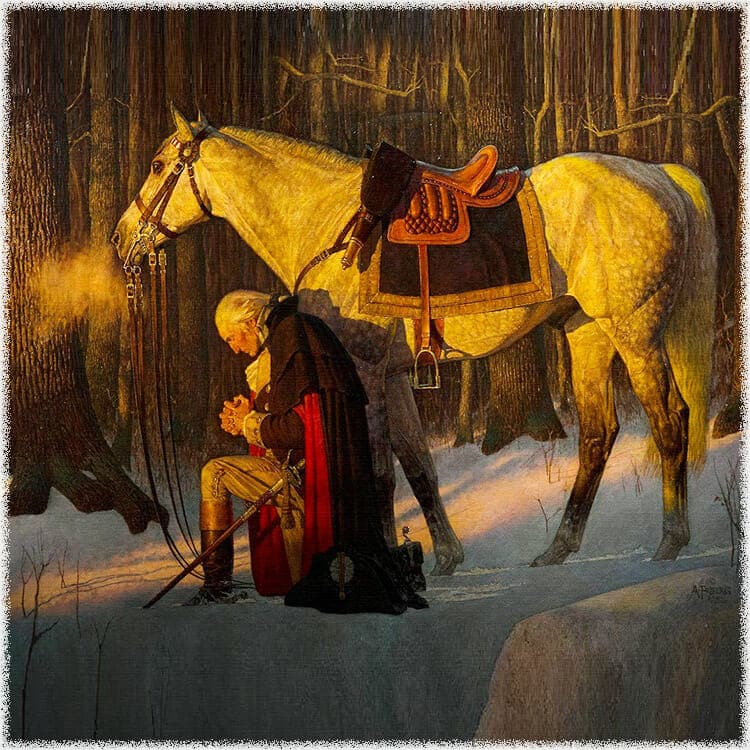

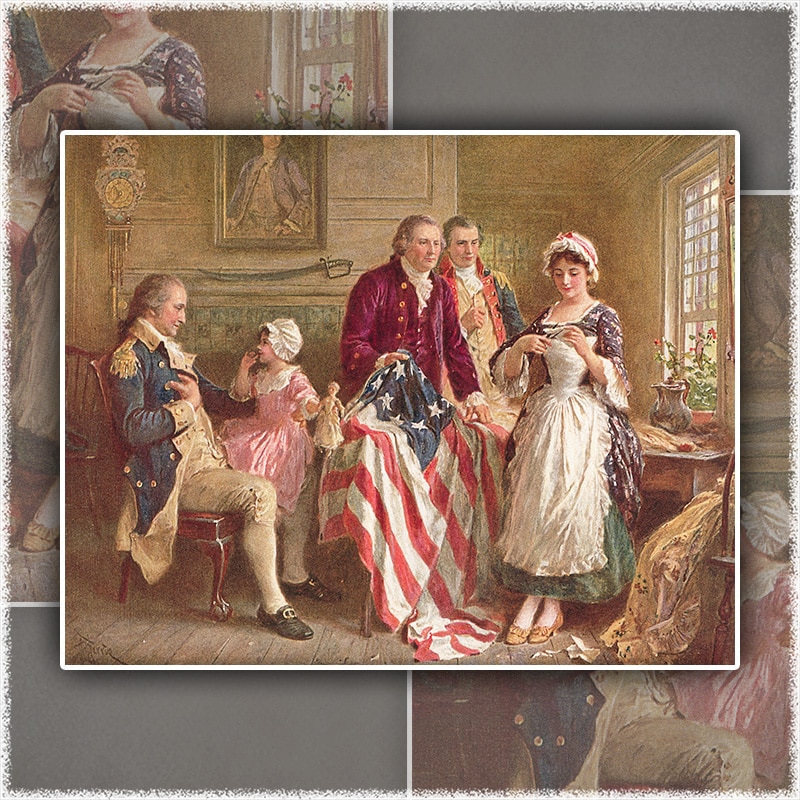

With this fact in mind, it should not come as a surprise to realize that the role of Betsy Ross, the one most credited with the development of the American flag, is also held up to doubt and ridicule. Betsy Ross, whose given name was Elizabeth Phoebe Griscom, was born January 1, 1752 and died January 30, 1836 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Married to John Ross at the age of twenty-one, she was widowed three years later, early in 1776—the same year that a small delegation from the American Continental Congress called upon her at her shop. She was subsequently married to two sea captains, both of whom were lost at sea; for this reason she is also referred to as Elizabeth Ashburn and Elizabeth Claypoole.[1] Though her Quaker Christian heritage is often associated with her, Betsy Ross and her family came to attend one of the most influential churches in America during the era of the War of Independence—Christ Church of Philadelphia.

Christ Church was an Anglican church and the church attended by other prominent leaders of the Revolution. The ministers of Christ Church, Rev. Jacob Duche and Dr. William White, were the first two chaplains of the Continental Congress. Following the Revolution, Dr. White became one of the founding fathers of the American Sunday School Union (please see discussion below). Dr. White was also instrumental in transitioning Anglicanism in America to the Episcopal Church. For its important role in the life of the nation during this critical era of American history, Christ Church is remembered as "the Nation's Church." Where Betsy Ross and her family sat in Christ Church is now remembered with a plaque—a pew not far from where George and Martha Washington sat in worship.[2] Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to America

Betsy's first husband, John Ross, worked as an upholsterer, and was the nephew of George Ross, Signer of the Declaration of Independence and one of three men appointed to design a flag for the new nation. Having been appointed by the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia, this committee of three appeared in the Ross family shop to request assistance with their assignment. The details of this meeting were a matter rehearsed by Betsy Ross for many years to come, and which her family described in detail after her death. In 1871, Betsy's daughter, Rachel Fletcher, formally composed and signed an affidavit detailing the events surrounding the making of America's first flag. In that account, Rachel wrote,

I remember having heard my mother Elizabeth Claypoole [or Betsy Ross]say frequently that she, with her own hands, (while she was the widow of John Ross,) made the first Star-spangled Banner that ever was made. I remember to have heard her also say that it was made on the order of a Committee, of whom Col. Ross was one, and that Robert Morris was also one of the Committee. That General Washington, acting in conference with the committee, called with them at her house. This house was on the North side of Arch Street a few doors below Third Street, above Bread Street, a two story house, with attic and a dormer window, now standing, the only one of the row left, the old number being 89; it was formerly occupied by Daniel Niles, Shoemaker. Mother at first lived in the house next East, and when the war came, she moved into the house of Daniel Niles. That it was in the month of June 1776, or shortly before the Declaration of Independence that the committee called on her. That the member of the committee named Ross was an uncle of her deceased husband. That she was previously well acquainted with Washington, and that he had often been in her house in friendly visits, as well as on business. That she had embroidered ruffles for his shirt bosoms and cuffs, and that it was partly owing to his friendship for her that she was chosen to make the flag. That when the committee (with General Washington) came into her store she showed them into her parlor, back of her store; and one of them asked her if she could make a flag and that she replied that she did not know but she could try. That they then showed her a drawing roughly executed, of the flag as it was proposed to be made by the committee, and that she saw in it some defects in its proportions and the arrangement and shape of the stars. That she said it was square and a flag should be one third longer than its width, that the stars were scattered promiscuously over the field, and she said they should be either in lines or in some adopted form as a circle, or a star, and that the stars were six-pointed in the drawing, and she said they should be five pointed. That the gentlemen of the committee and General Washington very respectfully considered the suggestions and acted upon them, General Washington seating himself at a table with a pencil and paper, altered the drawing and then made a new one according to the suggestions of my mother. That General Washington seemed to her to be the active one in making the design, the others having little or nothing to do with it. That the committee then requested her to call on one of their number, a shipping merchant on the wharf, and then adjourned. That she was punctual to her appointment, and then the gentleman drew out of a chest an old ship's color which he loaned her to show her how the sewing was done; and also gave her the drawing finished according to her suggestions. That this drawing was done in water colors by William Barrett, an artist, who lived on the North side of Cherry Street above Third Street, a large three story brick house on the West side of an alley which ran back to the Pennsylvania Academy for Young Ladies, kept by James A. Neal, the best school of the kind in the city at that time. That Barrett only did the painting, and had nothing to do with the design. He was often employed by mother afterwards to paint the coats of arms of the United States and of the States on silk flags. That other designs had also been made by the committee and given to other seamstresses to make, but that they were not approved. That mother went diligently to work upon her flag and soon finished it, and returned it, the first star-spangled banner that ever was made, to her employers, that it was run up to the peak of one of the vessels belonging to one of the committee then lying at the wharf, and was received with shouts of applause by the few bystanders who happened to be looking on. That the committee on the same day carried the flag into the Congress sitting in the State House, and made a report presenting the flag and the drawing and that Congress unanimously approved and accepted the report. That the next day Col. Ross called upon my mother and informed her that her work had been approved and her flag adopted, and he gave orders for the purchase of all the materials and the manufacture of as many flags as she could make. And that from that time forward, for over fifty years she continued to make flags for the United States Government.[3] Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to America

Rachel Fletcher's description of the details related to her mother's work in the construction of America's first flag is one of most authentic description of how this important symbol came into existence.[4] That those who deny this account base much of their arguments upon a lack of specific details in the Journals of the Continental Congress can be attributed to two important facts. First, that General Washington's invitation to Philadelphia in May of 1776 was secret, and second, the financing of the flag's production was private, requiring no payment from Congress. A quotation from a less-skeptical nineteenth-century history records these important facts:

On May 20, 1776, Washington was requested to appear before Congress on important secret military business. Major-General Putnam, according to Washington's letters, was left in command at New York during his absence. It was in the latter part of May 1776, that Washington, accompanied by Colonel George Ross, a member of Congress and by the Honorable Robert Morris, the great financier of the revolution, called upon Mrs. Betsy Ross, a niece of Colonel Ross.

The resources of Congress were meager and at best legislative action was then, as now, slow and tedious. The flag as indicated was wanted, and so Colonel Ross expedited its appearance by paying for the first order himself.[5]

Nearly a year after the three-man committee entered the shop of Betsy Ross, the Continental Congress took official action to ratify the decisions that had been made concerning the new flag. However, little is recorded in the Journal of the Continental Congress for Saturday, June 14, 1777 concerning this decision. The resolution simply reads,

Resolved, That the flag of the (thirteen) United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.[6]

Lay Minister Provides National Anthem

When observing patriotic events, American Christians will celebrate these occasions with greater appreciation when they realize yet another development related to the flag. Many Americans know that it was Francis Scott Key who conceived America's national anthem, but few realize or appreciate the Christian heritage that he also bequeathed to his fellow patriots. The night of September 13, 1814 passed slowly for Francis Scott Key and his companions as they watched a fierce British bombardment of Fort McHenry from the deck of one of the British ships that numbered among the British fleet near the mouth of the Potomac River at Baltimore harbor. Throughout the night, American shore fortifications returned fire, but toward morning, American cannonading fell silent. While his companions went below to get some sleep, Key continued to pace the deck until the first rays of light disclosed that indeed the "flag was still there." This victorious sight was the origin for his poem, The Star-Spangled Banner, which was first scribbled on the back of an envelope, the first verse of which has become our national anthem. Of the four verses he wrote, it is the second that most reflects his Christian convictions:

Oh thus be it ever, When freemen shall stand, Between their loved homes, And the war's desolation, Blest with vict'ry and peace, May the heav'n rescued land, Praise the Pow'r that hath made, And preserved us a nation, Then conquer we must, When our cause it is just, And this be our motto, "In God is our trust," And the star-spangled banner, In triumph shall wave, O'er the land of the free, And the home of the brave.

Like the overwhelming majority of America's Founding Fathers, Francis Scott Key was a deeply committed Christian. As a layman in the same denomination as Betsy Ross, the Protestant Episcopal Church, Key held lay reader's license, and for many years read the service and visited the sick within his church. One of the greatest contributions he made to America was the advancement of the Sunday school. Not only did he teach a Sunday school class at his church, he also served as a manager and vice president of the American Sunday School Union from its inception in 1824 until his death in 1843. The American Sunday School Union was responsible for establishing thousands of churches across America. Other prominent Americans also advanced the cause of Christ through the American Sunday-School Union, including signer of the Declaration of Independence and Surgeon General of the American Continental Army, Dr. Benjamin Rush; previously mentioned, congressional chaplain, Rev. Dr. William White; long-time vice president, Pennsylvania Governor John Pollock who, as director of the United States Mint in Philadelphia, first inscribed our currency with "In God We Trust"; Supreme Court Justice, Bushrod Washington, nephew of George Washington; Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall; American statesman, Daniel Webster; and later in the nineteenth century, the well-known evangelist, D. L. Moody; a relative of both early American presidents and organizer of more than 320 Sunday schools—whose name was also, John Adams; author of the Little House on the Prairie novel series, Laura Ingalls Wilder; and others concerned about Christianizing the youth of America and perpetuating the American Republic. Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to America

Interested in church hymnody, Francis Scott Key wrote the hymn, "Before the Lord We Bow" for a Fourth of July celebration in 1832. But the hymn for which he is most widely known first appeared nearly a decade earlier in 1823, being printed in a little hymnal published by Dr. William Muhlenberg, also of the Protestant Episcopal Church. That same year Key and Muhlenberg had both been appointed to a committee to prepare a new hymn-book for their denomination. Though not well-known, Key's hymn, "Lord, With Glowing Heart I'd Praise Thee" is a spiritual biography of one among many founding Fathers of America who took seriously their responsibility to Jesus Christ. Who again can sing the Star Spangled Banner in the same manner without reflecting upon Francis Scott Key's Christian commitment in this hymn—which may be sung to the tune of, "Love Divine, All Loves Excelling":

Lord, With Glowing Heart I'd Praise Thee

Lord, with glowing heart I'd praise thee

For the bliss Thy love bestows,

For the pardoning grace that saves me,

And the peace that from it flows.

Help, O God, my weak endeavor;

This dull soul to rapture raise;

Thou must light the flame, or never

Can my love be warmed to praise.

Praise, my soul, the God that sought thee,

Wretched wanderer, far astray;

Found thee lost, and kindly brought thee

From the paths of death away;

Praise, with love's devoutest feeling,

Him who saw they guilt-born fear,

And, the light of hope revealing,

Bade the blood-stained cross appear.

Lord, this bosom's ardent feeling

Vainly would my lips express;

Low before Thy footstool kneeling,

Deign Thy supplicant's prayer to bless;

Let Thy grace, my soul's chief treasure,

Love's pure flame within me raise;

And, since words can never measure,

Let my life show forth Thy praise.

Minister Writes Pledge of Allegiance

It was a Baptist minister, Francis Bellamy,[7] who composed the first pledge of allegiance to the American flag, in August 1892. Originally intended for use in the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the Americas, James B. Upham—the event promoter—hoped to instill national pride[8] in the classrooms of America where the pledge of allegiance was supposed to be used. Pastor Bellamy's original version was composed as follows:

I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Reverend Bellamy's original wording was changed slightly by the First and Second Flag Conferences of 1923 and 1924, and on December 28, 1945, the 79th Congress designated the pledge with its changes as the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag by Public Law 287. But one more Christian influence was to exercise itself upon the pledge before it assumed its final form which is used today. Flag Day—A Christian Contribution to America

It was the custom of some presidents to attend the church President Lincoln attended on the Sunday nearest February 12—Lincoln's birthday. On Sunday, February 7, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife observed that custom by attending the Lincoln Day Observance Service at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church and sitting in Lincoln's pew. The church's pastor, Rev. Dr. George MacPherson Docherty delivered a sermon based on the Gettysburg Address titled, "A New Birth of Freedom." During his sermon, he argued that the sentiment of the pledge of allegiance could be that of any nation. Using Lincoln's words, "Under God," Rev. Docherty argued that it was this expression that distinguished America from other nations, and it was this phrase that was missing from the pledge. Following the service, President Eisenhower enthusiastically engaged the pastor in conversation concerning this issue, and the following day, February 8, 1954, secured the assistance of Rep. Charles Oakman (R-Michigan) to introduce a bill to secure that purpose. On June 14, 1954, President Eisenhower signed the bill into law, saying,

From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty.... In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America's heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country's most powerful resource, in peace or in war.[10]

The more Americans realize how the irreligious and secularists have denied all Americans a right to the appreciation of their Christian heritage, the more deeply they should be resolved not to allow succeeding generations to be robbed of this important treasure. Lamentably, most church leaders are not prepared to offer those historical answers to the irreligious who ask a reason for the hope that is in them. Americans in general and Christians in particular must be willing to not only come to an appreciation of these important historical facts concerning our national heritage, but they must be willing to assume responsibility to advocate this heritage to succeeding generations. As President Eisenhower said,

. . . in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country's most powerful resource, in peace or in war.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] The years of her marriages are as follows: John Ross (m. 1773-1776), Joseph Ashburn (m. 1777-1782), John Claypoole (m. 1783-1817). She was also later known by her second and third married names: Elizabeth Ashburn and Elizabeth Claypoole.

[2] Millard, Catherine. The Rewriting of America's History. Camp Hill, PA: Horizon House Publishers, 1991, 271.

[3] "Affidavits," Betsy Ross Homepage (http://www.ushistory.org/betsy/flagaffs.html, June 12, 2015). Affidavit of Rachel Fletcher, a daughter of Elizabeth Claypoole (Betsy Ross) dated July 31, 1871. For a more detailed discussion, please see the account provided by her grandson, William Canby: William Canby, "The History of the Flag of the United States—A Paper read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (March 1870)," The Betsy Ross Homepage (http://www.ushistory.org/betsy/more/canby.htm, June 10, 2015). Orthography updated.

[4] A number of arguments are often advanced in support of the Betsy Ross account. First, Robert Morris was known to be a business partner of John Ross and was Betsy's cousin by marriage. The Journals of the Continental Congress show that Robert Morris also served with George Ross on the Marine Committee (6:894; Tuesday October 22, 1776), and it is stated that Betsy's flag was first flown from a ship.

Second, George Washington is known to have been in Philadelphia in the spring of 1776, where he served on a committee with John Ross' uncle George Read. Congress approved $50,000 for the acquisition of military supplies such as tents and "sundry articles" for the Continental Army. It is only reasonable that a flag would be among the "sundry articles" necessary to an army. See Marla R. Miller, Betsy Ross and the Making of America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2010), 173.

Third, Betsy Ross was must have enjoyed some reputation as a flag maker, for nearly a year later, on May 29, 1777, she was paid a large sum of money from the Pennsylvania State Navy Board for making flags. See "Did Betsy Ross really make the first American flag?," Ask History (http://www.history.com/news/ask-history/did-betsy-ross-really-make-the-first-american-flag, June 12, 2015).

Fourth, Robert Morris was on the Marine Committee at the time the vote was taken concerning the flag. Cf. Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789. ed. Paul H. Smith, et al. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976, 7:204-207, with Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. Washington, D.C.: 1904, 8:464.

Fifth, the oral history of this event is well supported with affidavits from three family members, including Betsy Ross' daughter, Rachel Fletcher, granddaughter, Sophia B. Hildebrant, and niece, Margaret Donaldson Boggs. See "Affidavits," Betsy Ross Homepage (http://www.ushistory.org/betsy/flagaffs.html, June 12, 2015).

Sixth, an 1851 painting ensconces the oral tradition regarding this event nearly twenty years prior to the March 1870 reading of the paper of grandson, William Canby, to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. A painting by Ellie Wheeler (daughter of renowned artist Thomas Sully) depicting the details of the event has been authenticated and verified by fine arts appraiser, Raymond M. Spiller, on April 17, 1985. This painting was repainted by renowned artist Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930) and is dated c. 1900-1920. This latter painting is the feature image of this article. The fact that the Wheeler painting has been authenticated to precede the Canby article by twenty years demonstrates that this event was well accepted by the Ross family and friends long before Canby's paper of 1870.

Seventh, detractors argue from silence. They insist that there are no Congressional records specifically stating Betsy Ross' role in the matter. Yet, what may be deduced from the Congressional record (as demonstrated above) is consistent with what Betsy Ross related to family and friends concerning this meeting. It is unreasonable to expect that a fledgling nation at war would have been as sophisticated in record keeping as these detractors may demand. It is very reasonable to expect that when General Washington was granted the privilege to purchase "sundry articles" by Congress that the matter of a flag would have been a consideration. Do military leaders have any interest in flags? In this same argument, the June 14, 1777 resolution adopted by Congress approving the flag should be taken into consideration. There is no discussion or debate in Congress concerning the make-up of the flag—absolutely none. The resolution summarily describes the appearance of the flag, suggesting that it had already reached a level of acceptability—and almost certainly, use—that debate or reconsideration was unnecessary or that it would have fallen on deaf ears. From all appearances, it was accepted by acclamation because it was already being used, which is consistent with Betsy Ross' account of events.

Eighth, one of the strongest arguments in defense of this event's authenticity is the proximity of a living witness in relation to the oral tradition that follows. What detractors wish to emphasis is that from the meeting in Betsy's shop in 1776 to her grandson's recounting of the event, nearly one hundred years lapse. What not one of these detractors—of which this author is aware—takes into consideration is that Betsy Ross passed away at the age of 84. She was a young woman of only 24 year whens this eventful meeting with this three-member committee occurred, and between her death and the nearest historical verification of Wheeler's 1851 painting is rendered, only fifteen years have passed—only the next day in historical terms! This fact lends tremendous credibility to the affidavits of the family! This was not contrived by loving family members wishing to secure a place for their loved one in American history. This was a family seeking to fill-in a blank page in American history!

Finally, that a flag had been made for the nation and Continental Army by 1776 is evident by the fact that this flag was carried across the Delaware on Christmas morning in the attack against Trenton. Without the account of the Ross family, there is absolutely no account of how America received its flag. The reason there was no debate in Congress when the flag resolution finally passed Congress a half-year later is because it was already in use, being received by popular acclaim.

[5] Addie Weaver, The Story of Our Flag Colonial and National, With Historical Sketch of the Quakeress Betsy Ross (Chicago: A. G. Weaver, 1898), 8, 10.

[6]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789. ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. Washington, D.C.: 1904, 8:464.

[7] Francis Bellamy drank deeply from the streams of socialism of his day. Choosing to emphasize socialism, he eventually wondered far from the roots of biblical Christianity.

[8] Upham is reported to have often told his wife, "Mary, if I can instill into the minds of our American youth a love for their country and the principles on which it was founded, and create in them an ambition to carry on with the ideals which the early founders wrote into The Constitution, I shall not have lived in vain." Margarette Miller, I Pledge Allegiance (Boston: Christopher Pub. House, 1946)

[9] "Pledge of Allegiance," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pledge_of_Allegiance, June 13, 2015).

[10] "God in the Whitehouse," God in America: PBS (http://www.pbs.org/godinamerica/god-in-the-white-house/, June 13, 2015).