After nearly a century of editing American history to exclude the Christian influences upon the birth of the United States, secularists appear upon the brink of successfully eclipsing the truth concerning America’s Christian origin. The truth, however, is that America would not exist as a separate nation, as it is known today, without the influence of Christians. The truth concerning the development of the Declaration of Independence and the origin of the United States of America cannot be accurately told without considering the major Christian influences that birthed the greatest nation in the history of the world. By understanding the direct influence that Christians and Christian influence exercised upon the formation of the Declaration of Independence, they will be more prepared to give an answer to every individual who seeks to know the source of the hope they possess.

Article Contents

One influence that is routinely overlooked by secular and irreligious historians is the legal context that preceded America becoming an independent nation apart from British rule. While North America and lands that would become the United States of America had been explored and claimed by other European government, the first permission granted by the English crown to explore the New World was granted to John Cabot (March 5, 1496) and Sir Humphrey Gilbert (June 11, 1578). The “patents” that granted permission to these men to explore the New World were filled with religious language that clearly associated the English government with advancing and extending the Christian Church to those lands that would come under the control of the British crown.[1]

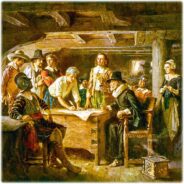

But the patents or permission to explore the New World on behalf of England were not the same as giving permission to settle in designated areas claimed by the crown. The first permission to settle within land that came to be claimed by England was given in the form of a charter to Sir Walter Raleigh to settle the Roanoke Colony in 1584—which failed. The charter for Jamestown was granted in 1606, with other charters being subsequently granted for territories that eventually became the Thirteen Colonies of England in North America. Like the patent given to John Cabot, these charters were filled with religious language that acknowledged that the British crown—by settling the new colonies—was doing so with the blessing of God and was advancing the cause of the Christian Church in turn. One of the many documents that demonstrated the Christian purpose of the settlers was the Mayflower Compact, regarded as the first legal document to be written in the British American colonies. The commitment to a Christian legal foundation by the settlers is evident:

Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our king and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the Northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine our selves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact laws, ordinances, acts constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cap-Cod the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland, the fifty fourth. Ano. Dom. 1620.[2]

In fact, the Christian convictions that composed the Mayflower Compact were evident in every single charter given for the English colonies in the New World. As the colonies began to make laws and provide for government for their individual colonies, the Christian convictions of the legislators of each colony became evident in the entire legal structure and the laws that were made.[3] One reason irreligious anti-American public educators must not allow students of public schools to read these documents without removing the numerous references to Christianity is because the overwhelming evidence demonstrates that America's legal foundation from the earliest era was clearly and convincingly Christian![4]

The Great Awakening and Government

Contemporary secular historians have for nearly a century attempted to hide the Christian influences that gave rise to the American Revolution. Since the 1920s and 1930s, a Marxist or economic rationale has been given for the Revolution: "…no taxation without representation."[5] This argument has been so successful that even among "conservatives" this is frequently the first reason offered for the American Revolution. But the fact is that if the American Revolution—like the French Revolution—had been the result of secularism, similar atrocities to those that occurred under the name of "secularism"[6] in France would have occurred in America. But this did not happen. The atrocities, bloodletting, and horrors of the French Revolution were a direct result of the lawless anti-God secularism of Voltaire, Rousseau, the Encyclopedists, and others who arrogantly rejected God's law and determined to impose their wills upon France, Europe, and the world.

In America, however, the colonists were determined to follow God's laws, not merely because of a slavish commitment to their Christian legal heritage, but because of deeper Christian convictions that had formed as a result of the First Great Awakening. The conviction that the law of the land must be founded upon God's law was the greatest contributing factor to reject the lawlessness of King George III.

The First Great Awakening was a spiritual revival that began in the 1730s and continued through 1743. Jonathan Edwards, one of the earliest leaders of the revival, was a minister at Northampton, Massachusetts from 1726-1750. While ministering in Northampton, Edwards witnessed two revivals come to his church and community. One was in the mid-1730s and the other was in the early 1740s. In 1740, the Anglican revivalist, George Whitefield (known as the "Grand Itinerant"), visited New England, the middle colonies, and the southern colonies, fanning into a great flame the smoldering embers of spiritual interest. Whitefield became friends with Benjamin Franklin who helped secure a place for Whitefield to preach in Pennsylvania, which was the beginning of Penn State University. For this reason, Whitefield's statue remains on the campus of Penn State to this day. The result of revivalistic efforts by Edwards, Whitefield, and others was the First Great Awakening, which provided a Christian moral code by which the actions of King George against the colonies could be evaluated and condemned in the Declaration of Independence.[7] For this reason, the Signers of the Declaration would emphasize "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God," for they regarded King George as having violated biblical standards of human government. With an understanding of the influence of the First Great Awakening upon the rise of the Revolution, it is easy to understand why the motto of the American Revolution became, "No king, but King Jesus!"

To ensure that America would come to deny and despise the influence of Christianity upon the origin of America, irreligious secularism has sought to malign and deny the Christian influence of the individual Founding Fathers. Thomas Jefferson was one of the most influential of the Founding Fathers. Benjamin Franklin, Jefferson, and others have been characterized as "deists" who rejected the principles of Christianity. However, historical evidence demonstrates that Franklin and Jefferson were not deists, and what is more, none of the Founding Fathers were deists! Efforts at portraying the Fathers as deists have been secular attempts to rob them of their Christian identities.[8]

Thomas Jefferson is regarded as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, and for this reason, secularist have believed that to depict Jefferson as anti-Christian would ensure their efforts to characterize the American Revolution as a "godless" secular effort.[9] But in fact, Jefferson claimed to be a Christian. In a letter to his friend and fellow Founding Father, Dr. Benjamin Rush, Jefferson affirmed his faith:

To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other.[10]

While the present author does not believe Jefferson was a Christian in an evangelical sense,[11] Jefferson believed the morals of Christ and Christianity must be part of the legal foundation of America. In fact, Jefferson was close friends with many pastors—including his own Anglican pastor, Rev. Charles Clay[12] —and the language of their sermons became part of his public writings for state and federal governments:

Contrary to what most secularists have foisted upon America, the language of Jefferson in public documents was not deistic, but Christian, and the language of the Declaration of Independence was Christian! A deist would never have believed that God continued to have an interest in the government of mankind as is affirmed within the Declaration of Independence.

To learn more concerning Thomas Jefferson's advocacy of Christianity, please click this box to read our article, Thomas Jefferson’s Wall of Separation Letter.After years of attempting to negotiate with King George on those issues that bitterly divided them from their Mother Country, the American Colonies were answered with only deepening hostility from the King and his Parliament. Negotiations were fruitless. Finally, on April 19, 1775 on the village green of Lexington, Massachusetts, the first shot of the Revolution was fired as British soldiers attempted to confiscate resources of the American patriots.

By the time the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence, the Thirteen Colonies were already at war with their Mother Country. The First Continental Congress had briefly convened from September 5 to October 26, 1774. One of the final decisions of the First Continental Congress was to make provision for a Second Continental Congress to meet on May 10, 1775 should the British government fail to repeal its harsh legislation against the Colonies. Forced to convene because of a rising tide of hostility toward the colonies, the Second Continental Congress met in six sessions from 1775 to 1781, at four different locations:

May 10, 1775 - December 12, 1776, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

December 20, 1776 - March 4, 1777, Baltimore, Maryland

March 5, 1777 - September 18, 1777, Philadelphia

September 27, 1777 (one day only), Lancaster, Pennsylvania

September 30, 1777 - June 27, 1778, York, Pennsylvania

July 2, 1778 - March 1, 1781, Philadelphia

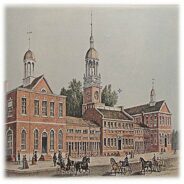

One of the most important sessions of this Congress was the first session that met in Philadelphia, at Independence Hall—of particular concern were the opening months of this session, June and July. On April 12, 1776, representatives from North Carolina proposed that the Colonies formally declare their independence from Britain. On May 15, a similar resolution was proposed by the Virginia delegation, and on June 7, Virginia representative, Richard Henry Lee, argued the motion before the Congress (making it the Lee Resolution). Finally, on Monday afternoon, June 10, 1776, the representatives to the Second Continental Congress voted to postpone a decision on the matter until Monday, July 1 to allow a "Committee of Five" men to draft a statement to present to the world, defending their resolve to remove the colonies from the British Empire. The Committee of Five was given a three-week period to complete the assignment and was composed of John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert Livingston of New York, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.[14]

Between June 10 and July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was drafted and revised until it received it final form. When the Committee of Five convened, a general outline was agreed upon, and John Adams persuaded the Committee to appoint Thomas Jefferson to draft a document in keeping with the outline that had been discussed. After Jefferson had composed his draft, he submitted it to the other members of the Committee who made extensive changes to it. Incorporating the suggestions of his fellow committee members, Jefferson composed a second draft which was submitted to the thirteen-member "Committee of the Whole" on June 28, bearing the title, "A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled."

On July 1, the entire Congress debated whether to declare independence from Britain. After hearing the debate, the members of the thirteen-member "Committee of the Whole" then voted, 9 to 2 (with two members abstaining) in favor of independence. On the afternoon of the following day, July 2, Congress received the report of the Committee of the Whole and declared the United Colonies independent of the British Empire and sovereign concerning their own government. Before adjourning on July 2, the Declaration was given a second reading by the Committee of the Whole. On July 3, additional modifications were made to the text of the Declaration, and late morning of July 4, Congress gave its consent to the final form. The document was referred back to the Committee of Five to make final corrections and prepare it for publication—which was complete in the early evening of July 4.

The final form of the Declaration of Independence was submitted to the printer, John Dunlap. The secretary of the Congress, Charles Thomson—who was an accomplished Bible scholar—attested that there was only one signature on the Declaration when it was submitted to the printer. The only signature on the Declaration at that time was the authenticating signature of the president of the Congress, John Hancock. Prior to the Revolution, Hancock was one of the wealthiest individuals of the Thirteen Colonies and a protégé of Samuel Adams. What is little known is that John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress and first signer of the Declaration of Independence, was the son and grandson of Christian pastors and was a graduate of Harvard while the college remained under the influence of its evangelical Christian origin. Calling attention to his heritage, one biographer notes:

His father and grandfather were both ministers of the gospel. His father is represented as a pious, industrious, and faithful pastor; a friend of the poor, and a patron of learning.[15]

For nearly a century, secularism has been attempting to deny the Christian origin of America. Not one of the Founding Fathers of America was a deist. If Benjamin Franklin was a deist, he would never have requested that prayer be offered in political gathering—deists do not offer prayer, neither do they believe God responds to prayer. And, Franklin would never have published such religious works as John Wesley's "Free Grace." If Jefferson had been a deist, he never would have endorsed and advocated Christianity as he did—both as the governor of Virginia and president of the United States. Just as the Constitution of the United States was born out of the context of Christianity, so the Declaration of Independence was conceived and birthed within the context of Christianity! It is no surprise that secularists, the irreligious, and even other world religions wish to usurp the place of Christianity by crediting themselves with that which is not and never will be theirs! Summarizing the relationship of Christianity to the birth of America, President John Quincy Adams, who was a boy at the time of the Revolution, related the following:

"The highest glory of the American Revolution was this: it connected, in one indissoluble bond, the principles of civil government with the principles of Christianity. From the day of the Declaration ... they (the American people) were bound by the laws of God, which they all, and by the laws of the Gospel, which they nearly all, acknowledged as the rules of their conduct."[16]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as authoritative reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

No anchor entries found.

[1] Federer, William J. The Original 13: A Documentary History of Religion in America’s First Thirteen States. Amerisearch, Inc., 2007, 27-28.

[2] “The Mayflower Compact,” Historic Documents (http://www.ushistory.org/documents/mayflower.htm, July 11, 2014).

[3] One of the best works describing the influence of Christianity upon the legal foundation of America is Federer, William J. The Original 13: A Documentary History of Religion in America’s First Thirteen States. Amerisearch, Inc., 2007

[4] For an outstanding work of the efforts to remove Christianity's influence on the historical development of America, please see this work: Millard, Catherine. The Rewriting of America’s History. Camp Hill, PA: Horizon House Publishers, 1991

[5] In the Declaration, it reads: "For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent." Bernstein, R. B., Comp. The Constitution of the United States of America with the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. New York: Barnes and Noble, Inc., 2002, 84.

[6] Secularism is a generic term, encompassing other terms such as irreligious, atheism, agnosticism, humanism, deism, and other similar expressions. In some way, these philosophies or worldviews deny honor to God in some way, whether as Creator, Sustainer, or Redeemer. Though these philosophies are very different, they—at some point—seek to deny God the place of honor that is rightfully His.

[7] For a scholarly discussion of Edwards, Whitefield, and the First Great Awakening, see, Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1972.

[8] Secular historians are little more than fictional writers who skew the facts to their own interests! See Barton, David. The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You’ve Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012, 12f.

[9] One such effort at reconstructing the origin of America through the lens of secular has been written by Isaac Kramnick and R. Laurence Moore, titled The Godless Constitution: A Moral Defense of the Secular State. Characteristic of secularists, Kramnick and Moore did not bother to footnote their initial release of this work; they expected the world to take their word for their falsifications.

[10] "Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Benjamin Rush (April 12, 1803)," The Federalist Papers (http://www.thefederalistpapers.org/founders/jefferson/thomas-jefferson-letter-to-benjamin-rush-april-12-1803, July 12, 2014).

[11] Jefferson denied the deity of Jesus—he believed Christ was a good moral teacher, but was not God. On the doctrine of Christ, Benjamin Franklin shared this opinion.

[12] Barton, David. The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You’ve Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012, 152-155.

[13] Beliles, Mark A. “Religion and Republicanism in Jefferson’s Virginia.” PhD dissertation: Whitfield Theological Seminary, 1993, 69-70; quoted in Barton, David. The Jefferson Lies: Exposing the Myths You’ve Always Believed About Thomas Jefferson. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012, 155.

[14] "Committee of Five," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Committee_of_Five, July 12, 2014).

[15] Lossing, B. J. Signers of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Geo. F. Cooledge, 1848, 22.

[16] From July 4, 1821.