Preacher Begins Prelude to American Revolution

Nearly one hundred years prior to the American Revolution, the causes for the break between Great Britain and America were already at work. While most Americans are unaware of the pivotal role American pastors exercised in the break with Britain, even fewer are aware that pastors were exercising similar roles of influence in American colonial life well before the Revolution. In fact, from the first settlement at Jamestown, Christian pastors exercised remarkable cultural influence upon America. This was true in all of the American English settlements and the Thirteen Colonies to which those settlements gave birth.American Revolution Prelude

One example of the prominence of pastors in the cultural and political life of the Colonies is found in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in early 1684. Not only does this anecdote illustrate the important role accorded to pastors in early America, but it also helps to explain why the Thirteen Colonies resorted to revolution.

Article Contents

Massachusetts and Colonial Government

To equate present-day government with the forms of government that prevailed among the English settlements of the New World is a grave mistake. The various forms of government that existed in early English settlements in America were numerous, and, those forms changed, largely at the discretion of the king. While an understanding of the various forms of government in the America colonies is very informative and helps explain why the Thirteen Colonies revolted, such a detailed study extends well beyond the interests of this brief article. However, a history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the origin of its charter is foundational to understanding the role of one pastor in particular and all pastors in general.

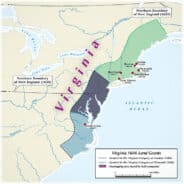

Though some English privateers attempted to establish English settlements in the New World,[1] the first permanent English settlement was achieved at Jamestown in 1607. Today, the name "Virginia" is used to designate a state, but this term was first given to a large area extending nearly from present-day New England to northern Florida. In 1606, King James I (whose name has been given to the King James Bible) encouraged settlement of this area by granting charters or permission to settle to two companies. King James granted a charter to the Virginia Company of London to settle the southern portion of this large tract of land, and to the Virginia Company of Plymouth he granted permission to establish English settlements in the northern portion. As an inducement to each company, King James set aside a large tract of land in between the two designated areas to be awarded to the company that could settle its primary or initial holding most quickly.

From the very beginning of the English settlements of the English territory of Virginia, government was very different. At Jamestown, government was controlled by the Virginia Company of London. When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620 at the northern tract of land controlled by the Virginia Company of Plymouth, they realized they did not have a charter to settle in present-day Massachusetts, and composed their own form of government, known as the Mayflower Compact. Only a few years passed before the Pilgrim Fathers were followed by other Puritans, many of whom fled to the New World to avoid religious persecution from the Anglican Church. Though some lesser known settlements sprung up, the next major development of English settlements occurred with the wave of Puritan immigrants in the 1630s.

Some of the earliest resistance to the authority of the English king did not begin with the American Revolution, but nearly a century earlier. Such efforts were generally the result of Christian pastors taking a stand against encroachment of the king upon the observance of their faith.

On March 4, 1629, a group of Puritan businessmen were granted a charter or license to conduct business affairs in present-day Massachusetts. This charter was known as "The Charter of Massachusetts Bay."[2] Though this charter was written to allow their Puritan company to conduct business in the New World, the Puritans quickly came to regard it as an opportunity to organize their understanding of a Christian society. Given the fact that those outside the Anglican Church were persecuted by Archbishop William Laud during the 1620s, they believed that their charter provided opportunity for a new way of life in America. Since the charter did not require them to reside in England to conduct their business, the Massachusetts Bay Company moved to their land holdings provided in the charter, and soon after established Boston. Here they elected their own governors and lived in accordance with their understanding of the teaching of the Bible. For fifty-five years the Massachusetts Bay Chapter remained in force, but then in 1683, the winds of change began to blow upon the Puritans and their Massachusetts Bay Colony.

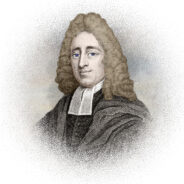

One of the leading ministerial families of New England history is the Mather family. Three generations of Mather ministers left a deep impression upon the life of Massachusetts and all New England. Immigrating to Boston in 1635, Richard Mather (1596-1669) helped found the church of Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1636, where he continued to minister until his death.[3] His son Increase Mather (1639-1723) was a Puritan minister and theologian and served as president of Harvard College and was a leading figure in resisting attempts on the part of the king to revoke the Massachusetts Bay Charter, as noted below.[4] Third generation Puritan minister, Cotton Mather (1663-1728) was also a distinguished theologian and author, writing 469 literary works on a vast number of subjects.[5]

After years of tension between England's kings and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, King Charles II-late in 1683-demanded that their charter be surrendered. Having been persecuted in England for their biblical faith, Puritans had enjoyed self-rule for more than half a century. Those settlements that had emerged as efforts for religious freedom were not prepared to once again submit to the yoke of Anglican bondage-something that was particularly true of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Leading the resistance were pastors. As one author notes, "Interestingly, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, most of New England's ministers were solidly behind the discreet resistance of the colonies."[6] And, when King Charles demanded that Massachusetts Bay return its charter, Increase Mather led the resistance. Having already developed his arguments against submitting the charter to the King's official in November of 1683 (see Appendix below), Mather traveled to Boston to attend a special meeting on January 23, 1684, which was convened specifically to determine how to respond to the King's demand. In his autobiography, he related the details surrounding this important event:

In the latter end of this year [1683], that came to pass, which occasioned no small trouble and temptation to me. For there arrived a vessel which brought the Kings declaration, wherein he signifieth to the country that except they would make a full submission and entire resignation to his pleasure, a Quo warranto should be prosecuted against their [colonial] Charter. Some desired me to deliver my apprehensions on the question whether the country could without sin against God make such a resignation as was proposed to them. Several papers were brought to me some that came out of England or Holland others written in New England which argued for the negative. I put those arguments into form, and added some more of my own, and then communicated them to some of the magistrates, who so well approved of them as to disperse copies thereof, that they came into many hands, and were a means to keep the country from complying with that proposal.[7] The other party conjectured me to be the author of that Mss. [manuscript] and were not a little displeased thereat. Nevertheless, I believe it was a good work, and I hope acceptable to the Lord.

Also on January 23 [1684]. The freemen of Boston [those qualified to vote] met to consider what they should do. The deputies of Boston and several others requested me to be present and to give my thoughts as to the case of conscience before them. In the townhouse I made a short speech to the freemen in these words, "As the Question is now stated, (viz. whether you will make a full submission and entire resignation of your Charter and privileges of it, to his Majesty's pleasure) we shall sin against God if we vote an affirmative to it. The scripture teacheth us otherwise. We know that Jephthah said, That which the Lord our God has given us, shall not we possess! And Naboth, though he ran a great hazard by the refusal, yet said, God forbid that I should give away the Inheritance of my Fathers. Now would it be wisdom for us to comply. We know that David made a wise choice, when he chose to fall into the hands of God rather than into the hands of men. If we make a full submission and entire resignation to [the] pleasure [of the King], we fall into the hands of men immediately. But if we do it not, we keep ourselves still in the hands of God, and trust ourselves with his providence and who knoweth what God may do for us? Moreover, there are examples before our eyes, the consideration whereof should be of weight with us. Our brethren hard by, what have they gained by their readiness to submit and comply, who if they had abode by their liberties longer would not have been miserable so soon. And we hear from London, that when it came to them would not make a full submission and entire resignation to pleasure, lest haply their posterity should curse them. And shall we do it then? I hope there is not one freeman in Boston that will dare to be guilty of so great a sin. However, I have discharged my conscience in thus delivering myself to you."

Upon this speech many of the freemen wept, and they said generally, we thank you Sir for this instruction and encouragement. The question being put to vote was carried in the negative nemine contradicente [nobody contradicting]. This act of Boston had a great Influence on the country, many other towns following this example.[8]

Though Massachusetts refused to surrender its charter in 1684, King Charles II annulled it in chancery court on June 18, 1684, and Rev. Increase Mather continued as a spokesman for the Colony in subsequent political discussions. In the Appendix below, the arguments of Increase Mather have been presented in their entirety. Though Mather expresses concern over the fact that public official-if appointed by the king-would not be accountable to the vote of the people, his greatest fear is that surrendering their charter will result in a loss of religious freedom.

In contemporary discussions concerning government, secularists argue that no allowance or consideration should be granted to religious influence. Such an argument is un-American! Increase Mather makes it abundantly clear in his arguments, that all human government must submit to the "majesty of heaven"-something that Thomas Paine also argued in his well-known work, Common Sense.[9] King George III regarded the American Revolution as a "Black-robe Rebellion" because American pastors argued for resistance to monarchs who usurped the rights and privileges granted by the "majesty of heaven." Among those who led the way nearly a century earlier was the Puritan minister, Increase Mather! May God grant his people ministers equally discerning in each generation.

Prior to his meeting in Boston on January 23, 1684, Increase Mather formally developed his arguments against surrendering the Massachusetts' Bay Charter. Though his style of writing may appear too academic, readers willing to invest the time and effort to study his arguments carefully will not be disappointed.

Arguments Against Relinquishing the Charter

[By Rev. Increase Mather]

Question. Whether the government of the Massachusetts Colony in New England ought to make a full submission and entire resignation to the pleasure of the Court, as to alterations, called regulations, of their charter?

Answer. Neg[ative]. They ought not to do thus; as may be concluded from the following arguments:

Argument 1. For the government of the Massachusetts to consent unto proposals or alterations, called regulations, which will be destructive to the interest of religion, and of Christ's kingdom in that colony, cannot be done without sin and great offence to the majesty of heaven. But so it will be, if they make a full submission and entire resignation to the pleasure of the Court; for such a submission and resignation cannot be declared without an intimation of consent; and the people in New England, being Non-Conformists, have no reason to believe that their religion and the Court's pleasure will consist together; especially considering there is not one word about religion mentioned in the king's declaration.

Arg. 2. If the government of the Massachusetts have no sufficient reason to think that they shall gain by a full submission and entire resignation to the pleasure of the Court, as to alterations in their charter, then they ought not to do thus. But they will gain nothing thereby. The consequence will be granted by everyone. The truth of the assumption that they have no reason to think that they shall gain by such a submission and resignation, appears from three reasons. -Reason 1. If the intended alterations, called regulations, of their charter, will be destructive to the essentials thereof, then they have no reason to think they shall gain thereby. But that the designed alterations will be destructive to the life and being of their charter, is manifest from this reason: If they must have no governor but what the Court shall please, and this governor have power to put out and put in what magistrates he (with the Court's approbation) shall please, without the consent of the people in that jurisdiction; that is an essential alteration, and destructive to the vitals of the charter. That this is intended, is clear; for it is designed to reduce matters in New England to the same state that London charter is reduced unto; therefore they that have issued out a quo warranto against the charter, have caused a copy of the proceedings and alterations, called regulations, of the charter of the city of London, to be sent to New England. Also, the ministers of state did some of them expressly declare to the agents of the Massachusetts Colony, that this was intended. This will be a destructive alteration, and no better than a condemnation of the charter. -Reason 2. If they that have already, made a full submission and entire resignation to the pleasure of the Court, have gained nothing by it, there is no reason for New England to think that they shall advantage themselves thereby. But all those corporations in England who have submitted to the Court's pleasure, have gained nothing thereby, but are in as bad a case as those that have stood a suit in law, and have been condemned. Moreover, in New England they have an instance before their eyes, enough to convince them, viz. that in the eastern parts, who, if they had not submitted so soon, might have lived longer. -Reason 3. If the people of the Massachusetts will, by a resignation, make themselves incapable of recovering their charter again, then they will gain nothing thereby. But so it will be. Whereas, if they maintain a suit, though they should be condemned, they may bring the matter to Chancery or to a Parliament, and so may possibly in time recover all again. It appears then, that they will rather lose than gain by a resignation, supposing a non-resignation should issue in the condemnation of their charter.

Arg. 3. For the government of the Massachusetts now to act contrary unto that way wherein God hath owned their worthy predecessors, ought not to be. But if they make such a full submission and entire resignation as is urged, they will do so. For when, in the year 1638, there was a quo warranto against the charter, their worthy predecessors neither did nor durst they make such a submission and resignation as was then expected from them. And when, in the year 1664, it was the Court's pleasure to impose commissioners upon the government of the Massachusetts, they did not submit to them. God has owned those worthy predecessors, in their being firm and faithful in asserting and standing by their civil and religious liberties. Therefore their successors should walk in their steps, and so trust in the God of their fathers, that they shall see his salvation.

Arg. 4. For the government of the Massachusetts to do that which will gratify their adversaries, and grieve their friends, is evil. But such a submission and resignation as is urged will do so. Hoc Ithacus velit. They may perceive by the chief instrument of their trouble, that he, and others, as good friends to New England as himself, had much rather the Massachusetts should resign than that they should make a defense in law. Is that likely to be for the good of the colony, which such enemies do so importunately desire? They know that it will sound ill in the world for them to take away the liberties of a poor people of God in a wilderness: Therefore they had rather that that people should give them up themselves, than that they should by main force be wrested out of their hands. They know that a resignation will bring slavery upon them sooner than otherwise would be. And as this will gratify adversaries, so it will grieve their friends, both in other colonies and in England also, whose eyes are now upon New England, expecting that the people there will not, through fear and diffidence, give a pernicious example unto others.

Arg. 5. The government of the Massachusetts ought not to yield blind obedience to the pleasure of the Court. But if they make such a full submission and entire resignation as is urged, they will yield blind obedience; for they do not know what all those regulations are. There is nothing said in the king's declaration concerning the religious liberties of the people in New England; and how, if popish councils should influence so far, as that one regulation must be conformity, in matters of worship, with the established church government in England. Inasmuch as it was objected by a principal minister of state to the agents of the Massachusetts, that in their commission there was that clause, that they should not consent to anything that would be inconsistent with the main end of their coming to New England, there is reason to fear that part of the design in alterations (called regulations) is to introduce and impose that which will be inconsistent with the main end of their fathers' coming to New England. And therefore for them to submit fully to things called regulations, according to the Court's pleasure, cannot be without great sin and incurring the nigh displeasure of the King of kings.

Arg. 6. If the government of the Massachusetts Colony in New England should act contrary unto that which has been the unanimous advice of the ministers of Christ there, they have cause to suspect they shall miss it in so doing. But if, for fear of bad events, they shall make a full submission and entire resignation of their charter, to be altered or regulated according to the Court's pleasure, they will act contrary unto that which has been the unanimous advice of the ministers in that colony. For on the, 4th of January, 1680, the ministers having then a case of conscience before them, returned answer in these words: "We conceive that this honored Court ought to use utmost care and caution that no agents of ours shall act, or shall have power to act, anything that may have the least tendency towards yielding up or weakening this government as by patent established. It is our undoubted duty to abide by what rights and privileges the Lord our God in his merciful providence hath bestowed on us. And whatever the event may be, the Lord forbid we should be any way active in parting with them." This advice was given after a solemn day of prayer; and all the ministers then present (who were the greatest part of what are in the colony) concurred in it. Now, if in the year 1680 it were an undoubted duty to abide by the privileges which the Lord hath bestowed on us, it cannot but be a sin in the year 1683 to submit and resign them all to the Court's pleasure. And it is to be hoped, that the ministers of God in New England have more of the spirit of John Baptist in them, than now, when a storm hath overtaken them, to be reeds shaken with the wind. The priests were to be the first that set their foot in the waters, and there to stand till the danger was past. Of all men, they should be an example to the Lord's people, of faith, courage and constancy. Unquestionably, if blessed Mr. [John] Cotton, [Thomas] Hooker, [John] Davenport, [Richard] Mather, [Thomas] Shepard, [Jonathan] Mitchel, were now living, they would, (as is evident from some passages in the printed books of divers of them) say, Do not sin in giving away the inheritance of your fathers.

Arg. 7. For the government to submit and resign to the pleasure of the Court, without the consent of the body of the people, ought not to be. But the generality of the freemen and church members throughout New England will never consent hereunto. Therefore the government may not do it.

Objection 1. There is no such thing as a resignation of the charter intended; it is only a submission to alterations in some circumstances, in order to preserving the substance of the charter entire.

Answer 1. The example of London set before New England as a copy for them to write after, does most clearly prove the contrary unto this opinion. -2. In case the government of the Massachusetts return their answer in such general terms as the Court in England shall take to be an entire resignation to their pleasure, and when the regulations appear to be destructive to the vitals of their charter, the Massachusetts should refuse to comply therewith, it will be said they have dealt deceitfully and untruly. -3. In case the government plainly signify that they submit to regulations only as to circumstances, and with a proviso that the life of their charter may be preserved, they will incur as much displeasure as if they maintain their right as far as law and equity will defend them. Yea, then the prosecution of the quo warranto will as certainly go on.

Obj. 2. They have legally forfeited their charter, and therefore may without sin resign.

Ans. 1. If by legal forfeiting of their charter be meant, that according to some corrupt and unrighteous laws they have done so, notwithstanding that, they may not without sin resign. -2. It is not to be believed that they have forfeited their charter, according to the laws of righteousness and equity; for then they that take away all their privileges from them will do them no wrong; nor shall they that condemn their charter, be themselves condemned for that action by the Lord the righteous Judge. He that acknowledgeth this, doth New England more wrong than a little. And if the charter be not forfeited in the sight of God, and according to the rules of his word, it is a sin to submit or consent that the Court should alter it according to their pleasure.

Obj. 3. The Lord's people were bid to go out to the king of Babylon, and the emperors of Babylon and Persia had dominion over the bodies and cattle of the Jews at their pleasure, Neh. 9. 37. Therefore, New England ought to submit to the pleasure of the Court.

Ans. He scarce deserves the name of an Englishman that shall thus argue. Because those monarchs were absolute, must Englishmen, who are under a limited monarchy, consent to be in that misery and slavery which the captive Jews were in? By this argument, no man may defend his legal right, if the king, or any commissioned by him, shall sue him. And suppose someone obtaining a commission at Court, should bid this objector yield up his house and farm, would he say it is my duty so to do? For the emperors of old had dominion over the bodies and cattle and estates of their subjects at their pleasure.

Obj. 4. But what Scripture is there against this full submission and entire resignment?

Ans. There is the sixth commandment. Men may not destroy their political any more than their natural lives. All judicious casuists say, It is unlawful for ä man to kill himself when he is in danger, for fear he shall fall into the hands of his enemies, who will put him to a worse death, Sam. 31. 4. There is also that Scripture against it, Judges 11. 24, 27; and that 1 Kings 21. 3. The civil liberties of the people in New England are part of the inheritance of their fathers; and shall they give that inheritance away?

Obj. 5. They will be exposed to great sufferings if they do it not.

Ans. Better suffer than sin, Heb. 11. 26, 27. Let them put their trust in the God of their fathers, which is better than to put confidence in princes. And if they suffer because they dare not comply with the wills of men against the will of God, they suffer in a good cause, and will be accounted martyrs in the next generation, and at the great day.[10]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] See, "Roanoke Colony," Wikipedia, January 28, 2018; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_Colony.

[2] "The Charter of Massachusetts Bay: 1629," Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, January 27, 2018; http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass03.asp.

[3] Daniel Reid, Robert and et al, Dictionary of Christianity in America, s.v. "Mather, Richard (1596-1669)."

[4] Daniel Reid, Robert and et al, Dictionary of Christianity in America, s.v. "Mather, Increase (1639-1723)."

[5] Daniel Reid, Robert and et al, Dictionary of Christianity in America, s.v. "Mather, Cotton (1663-1728)."

[6] Peter Marshall and David Manuel, The Light and the Glory (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Fleming H. Revell, 1977), 257.

[7] Increase Mather, "Arguments against Relinquishing Charter," in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), 74-81.

[8] Increase Mather and M. G. Hall ed., "The Autobiography of Increase Mather," The Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 71, no. 2 (1961): 307-308. Orthography updated

[9] Stephen Flick, "Thomas Paine Argues, 'No King but God'," Christian Heritage Fellowship, January 28, 2018; https://christianheritagefellowship.com/thomas-paine-argues-no-king-but-god/.

[10] This paper, so characteristic of the early habits of resistance to tyranny in New England, was probably written in November, 1683. Mather, "Arguments against Relinquishing Charter," in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 74-81. Orthography updated.