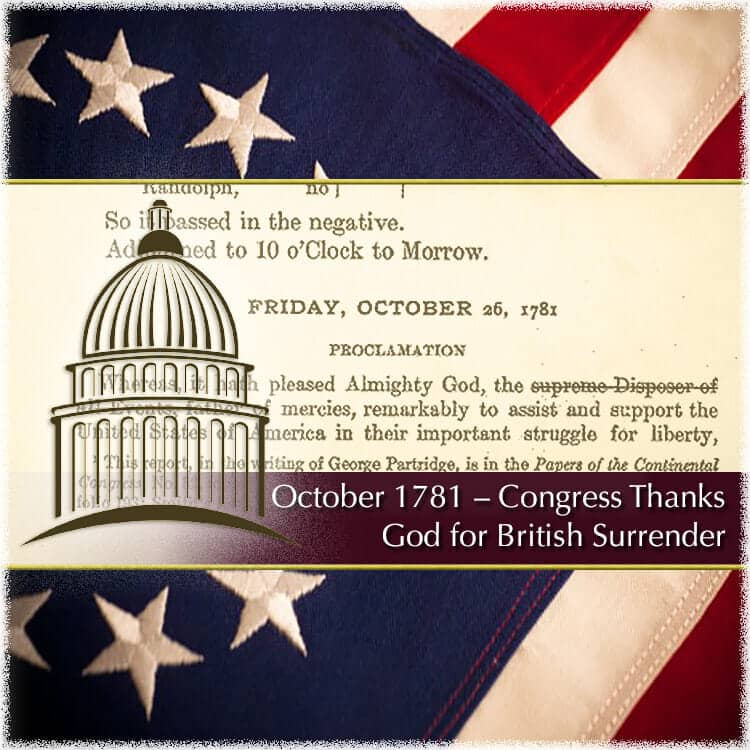

October 26, 1781 – Congress Thanks God for British Surrender

America's Christian heritage is interwoven with the birth and development of the nation. But, since the early part of the twentieth century, groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have done everything within their power to deny Christianity's influence upon the nation. These groups have covered-up the historical facts that clearly relate the influence America's Founding Fathers accorded Christianity in the birth and development of the nation. However, the Journals of the Continental Congress record the influence Founders gave to the Christian faith. From 1775 to 1784, Congress issued sixteen spiritual proclamations calling upon the thirteen states to humble themselves, fast, pray, and give thanks to God. One of the most important of these proclamations was issued on October 26, 1781—following the surrender of the British Army under Lord Cornwallis, effectively bringing the American Revolution to an end.

The subject addressed in this article is discussed at greater length in When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God. Christian Heritage Fellowship would be honored to work with individuals, businesses, churches, institutions, or organizations to help communicate the truth concerning the positive influence of the Christian faith by providing bulk pricing: Please contact us here... To purchase a limited quantity of this publication, please click: Purchase here...

Article Contents

By the time the fall spiritual proclamation for thanksgiving of 1781 rolled around, Congress had elected a new president to order its affairs. Resigning because of poor health, Samuel Huntington was succeeded by Thomas McKean of Delaware. As the eighth president of Congress, McKean occupied this position for only a few months, serving from July 10, 1781 to November 4, 1781. Yet, it was during this brief period in office as president that the British Army under Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, effectively bringing the American Revolution to an end.

Thomas McKean was born in New London Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. After receiving seven years of schooling under Rev. Francis Allison in his New London academy, Thomas studied law under his cousin, David Finney of New Castle, Delaware. Admitted to the bar in Delaware at age twenty, he was soon on his way as a successful lawyer and politician. He was appointed deputy attorney-general in 1756 and clerk of the Delaware Assembly for two years before being elected to the Assembly for a period of seventeen years.

In 1774, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where he soon became involved in the First and Second Continental Congresses. A few days after casting his vote in favor of independence in July 1776, he left Congress to serve as colonel of the Fourth Battalion of Pennsylvania Associators, a militia force created by Benjamin Franklin in 1747.[1]

When Delaware framed its first constitution, McKean exercised significant influence upon its development. As his interests gravitated toward Philadelphia once again, he was commissioned Chief Justice of Pennsylvania on July 28, 1777, though he remained active in Delaware politics as well, and held offices in both states over the next six years (1777-1783). McKean also served briefly as President of Delaware (September 22, 1777 to October 20, 1777) and Governor of Pennsylvania, serving three terms from December 17, 1799 until December 20, 1808.[2] Though his time in office as President of Congress was very brief, Thomas McKean had the privilege of occupying that office during one of the most important moments in American history.

The early months of 1781 offered little indication that the course of the year would be any different than the one that had preceded it. With a fresh infusion of French financial and military assistance, American prospects became more hopeful. Following the defeat at Camden, South Carolina, General Washington placed the Quaker, Nathanael Greene in command of the American southern forces. With this change in command, British dominance on the battlefield began to wane.

The focus of significant military efforts began in late 1780 to shift toward Virginia. After betraying his country, Benedict Arnold was given the rank of brigadier general by the British and sent to raid Virginia in December 1780. By January 1781, Arnold was successfully destroying sites of military and economic importance in Virginia.

From South Carolina and major victories there, the commander of southern British forces, General Charles Cornwallis, began to move northward. But, the tide of success began to shift in favor of American forces. Moving toward North Carolina, one wing of Cornwallis' army was defeated in the October 7, 1780 Battle of Kings Mountain (fought just below the southern border of North Carolina, in South Carolina), and another wing of his army was defeated in the January 17, 1781 Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina.

Undaunted by his losses, Cornwallis set out in pursuit of the main southern army of Americans into North Carolina, which was under the command of General Nathanael Greene. Believing Greene supplied himself from resources in Virginia, Cornwallis crossed into Virginia, and being commanded by his superior to find a deep-water port where he could be resupplied, Cornwallis did so at Yorktown, Virginia.

Americans and their French allies also converged upon Virginia. Moving with American and French forces from an area surrounding New York City, General Washington marched toward Yorktown. In the Chesapeake Bay surrounding Yorktown, French and British ships met in battle on September 5, and when the smoke cleared, the French had vanquished the British. By September 28, Washington's Franco-American army had blockaded Yorktown, and by October 6 began to dig siege trenches. The siege of Yorktown ensued. With the French victory in the Chesapeake, the British in Yorktown were completely surrounded on both land and sea. By October 17, negotiations began between the two parties to obtain terms of peace. Two days later, the terms of peace were agreed to and 8,000 British soldiers surrendered, effectively ending the Revolution.

Committee Composes Proclamation

While no attempt will be made to consider the members of Congress appointed to the committee to compose the fall thanksgiving proclamation, what may be noted is the date on the Journal entries related to this proclamation. Nearly a month and a half passes between the appointment of the committee and congressional approval for the proclamation.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 1781

On motion of Mr. [Roger] Sherman, seconded by Mr. [John] Witherspoon,

Resolved, That Thursday, the 13th day of December next, be appointed to be observed as a day of public thanksgiving throughout the United States; and that a committee be appointed to prepare and report a proclamation suitable to the occasion: The members, Mr. [John] Witherspoon, Mr. [Joseph] Montgomery, Mr. [James Mitchell] Varnum, Mr. [Roger] Sherman.[3]

Notice, that in the following excerpt Congress made attendance at a worship service an official act of Congress to "return thanks to Almighty God" for the victory at Yorktown. Though the attendance at Christian worship for the first inauguration of George Washington was also a matter of an official act of Congress in 1789, this official act in Congress on October 24, 1781 is among the very first acts in which Christian worship was made an official congressional act.

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 24, 1781

Resolved, That Congress will, at two o'clock this day, go in procession to the Dutch Lutheran church, and return thanks to Almighty God, for crowning the allied arms of the United States and France, with success, by the surrender of the whole British army under the command of the Earl of Cornwallis.[4]

Because of the momentous events related to the siege and victory at Yorktown, the report of the committee charged with composing the fall thanksgiving day proclamation was delayed nearly six weeks. Two days after Congress worshipped together at the Dutch Lutheran church, it finally was submitted by the committee and adopted by Congress as a whole. It read:

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1781

The committee, consisting of Mr. Witherspoon, Mr. Montgomery, Mr. Varnum, Mr. Sherman, appointed to prepare a recommendation for setting apart a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, reported the draught of a proclamation, which was agreed to as follows:

PROCLAMATION

Whereas, it hath pleased Almighty God, the father of mercies, remarkably to assist and support the United States of America in their important struggle for liberty, against the long continued efforts of a powerful nation: it is the duty of all ranks to observe and thankfully acknowledge the interpositions of his Providence in their behalf. Through the whole of the contest, from its first rise to this time, the influence of divine Providence may be clearly perceived in many signal instances, of which we mention but a few.

In revealing the councils of our enemies, when the discoveries were seasonable and important, and the means seemingly inadequate or fortuitous; in preserving and even improving the union of the several states, on the breach of which our enemies placed their greatest dependence; in increasing the number, and adding to the zeal and attachment of the friends of Liberty; in granting remarkable deliverances, and blessing us with the most signal success, when affairs seemed to have the most discouraging appearance; in raising up for us a powerful and generous ally, in one of the first of the European powers; in confounding the councils of our enemies, and suffering them to pursue such measures as have most directly contributed to frustrate their own desires and expectations; above all, in making their extreme cruelty to the inhabitants of these states, when in their power, and their savage devastation of property, the very means of cementing our union, and adding vigor to every effort in opposition to them.

And as we cannot help leading the good people of these states to a retrospect on the events which have taken place since the beginning of the war, so we beg recommend in a particular manner that they may observe and acknowledge to their observation, the goodness of God in the year now drawing to a conclusion: in which

The Confederation of the United States has been completed in which there have been so many instances of prowess and success in our armies; particularly in the southern states, where, notwithstanding the difficulties with which they had to struggle, they have recovered the whole country which the enemy had overrun, leaving them only a post or two on or near the sea: in which we have been so powerfully and effectually assisted by our allies, while in all the conjunct operations the most perfect union and harmony has subsisted in the allied army: in which there has been so plentiful a harvest, and so great abundance of the fruits of the earth of every kind, as not only enables us easily to supply the wants of the army, but gives comfort and happiness to the whole people: and in which, after the success of our allies by sea, a General of the first Rank, with his whole army, has been captured by the allied forces under the direction of our Commander in Chief.

It is therefore recommended to the several states to set apart the 13th day of December next, to be religiously observed as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer; that all the people may assemble on that day, with grateful hearts, to celebrate the praises of our gracious Benefactor; to confess our manifold sins; to offer up our most fervent supplications to the God of all grace, that it may please Him to pardon our offenses, and incline our hearts for the future to keep all his laws; to comfort and relieve all our brethren who are in distress or captivity; to prosper our husbandmen, and give success to all engaged in lawful commerce; to impart wisdom and integrity to our counsellors, judgment and fortitude to our officers and soldiers; to protect and prosper our illustrious ally, and favor our united exertions for the speedy establishment of a safe, honorable and lasting peace; to bless all seminaries of learning; and cause the knowledge of God to cover the earth, as the waters cover the seas.[5]

Far from abandoning their faith when they entered the halls of government, America's Founding Fathers understood it was the "duty" of all people to express their gratitude for the goodness of God: "…it is the duty of all ranks to observe and thankfully acknowledge the interpositions of his Providence in their behalf." In fact, in most of the sixteen spiritual proclamations issued by Congress from 1775 to 1784, Congress insisted it was the "duty" of citizens to give thanks to God for His blessings.

The implication of this proclamation and others like it is that judges who deny citizens the right to publicly express their faith and gratitude to God is denying Americans the privileges Founding Fathers insisted was a duty! Americans may rightly question these liberal activist judges: "Why do you doubt and deny what our Founding Fathers insisted was an obligation?"

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

No index entries found.

[1] "Thomas Mckean," Wikipedia, October 3, 2017; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_McKean.

[2] Dictionary of American biography, s.v. "Mckean, Thomas."

[3] Journals of the Continental Congress, 21:957-958.

[4] Journals of the Continental Congress, 21:1071.

[5] Journals of the Continental Congress, 21:1074-1076.