Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

- 426

- 427shares

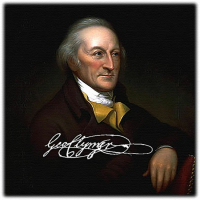

One of the great challenges presented to every generation of Christians is the Christianizing of their respective generations. Sinister forces are constantly at work, seeking to scar and mar the cultural advantages and progress that are the results of biblical Christianity. Supreme Court Justice, David Brewer, understood this fact when he penned his book, The United States a Christian Nation (see below), urging Americans to continue their Christian civilizing influence.[1] The Gospel calls every generation of Christians in every land to leaven and to enlighten—to further civilize the nations of which they are a part, resisting the influences of spiritual and cultural decay.Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Lamentably, leaders and laity in the Christian Church have often allowed corrupting influences to dilute and destroy the civilizing influences of the Gospel. Though many examples could be cited to demonstrate this point, the most glaring example of this fact is seen at the close of October and beginning of November. For some Christians, the Triduum of All Hallows or Triduum of All Saints is observed at this time of year. In America, usually only the first of this three-day observance holds any significance—October 31, Halloween. For Christians in the high church or Roman Catholic tradition, October 31 is known as All Hallows' Eve[2] (from which we derive the term "Halloween"), while November 1 is referred to as All Hallows Day ' (All Saints Day), and November 2 as All Souls' Day.[3] Because these three distinct observances cover a three-day period, the Latin term "triduum" is used by this Christian tradition to describe this event as a whole. To assess the value of these events for Christian living, the devoted believer has a right to question their origin and the manner of their observance.Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Table of Contents

Druidism, The Religion of the Celts

Polytheism—Belief in Many Gods

No Scripture

Astrology and the Black Arts

Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe

Human and Animal Sacrifices

Samhain—The Beginning of Halloween

All Saints' Day

All Souls' Day

Use of Costumes

Impersonating the Saints

Use of Candles

While some Christian writers seek to place blame upon Halloween's pagan origin, they fail to realize the contributions that corrupted Christianity have contributed to elements of this event as well. Careful assessment of the rise and development of Halloween or the three-day observance of Triduum of All Hallows (October 31-November 2) reveals that paganism was not the only influence upon these observances.

One of the most important influences upon the rise and development of what is now known as Halloween was a group of people who shared a common ethnic, linguistic, and cultural origin, known as the Celts . It is common to associate the Celts with the British Isles, but the land originally inhabited by the Celts was far more extensive. By 450 BC, Celtic culture had expanded to the British Isles, France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, northern Italy, and as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians). Along with many other people groups, the Romans called the Celts "barbarians."[4] Though the Celts and their culture extended over a vast territory, the strain of Celtic culture that most influenced America and the development of Halloween came from the British Isles.[5] The common religion among the Celtic people in mainland Europe and the British Isles was Druidism.

Druidism, The Religion of the Celts

Druidism, the religion of the Celts, flourished among these people roughly from the second century B.C. to the second century A.D., but in those areas of the British Isles not occupied by the Romans, Druidism survived until it was displaced by Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries. The term druid was given to their spiritual leaders[6] who were organized into three classes or offices: prophets, priests, and bards. Druids were highly esteemed in Celtic culture and often functioned in various capacities including, priest, religious leader, judge, and civil administrator, with supreme power and authority being vested in an "arch druid."

When studying the influence of the Celts and their influence upon the rise of Halloween, it is very easy to confuse modern Druidry (also known as Neo-Druidism or Neo-Druidry) with ancient Druidism—something that this article will seek to avoid. Many Christian writers, eager to defend the truth of Scripture, fail to distinguish between the two groups. Having more information on modern Druidry, they often place the beliefs and practices of this younger form upon the older Druidism that exercised greater influence upon Halloween and Hallowmas.[7]

Several practices of the older form that influenced America and gave rise to modern day observance of Halloween are of importance to our study. The first information known to exist concerning their practices comes from ancient sources. Two ancient Greek sources, which no longer exist, first recorded general information about druid priests (about 300 BC). The first known text to describe the druids in detail is provided by Julius Caesar, about the 50s or 40s BC (Commentarii de Bello Gallico, VI), and though some modern scholars seek to discredit Caesar's accounts of the practices of the druids, accounts from other ancient writers such Cicero, Diodorus Sicilus, Strabo and Tacitus support Caesar.[8]

Polytheism—Belief in Many Gods

From what ancient evidence there is, it is apparent that the druids and Celtic people were polytheists, believing in many gods and goddesses. As the term paganism is used to identify people groups who believed in many gods, uninfluenced by the Hebrew and Christian idea of one God, this term may appropriately be applied to the Celts and their druid priests. Before the influence of St. Patrick’s ministry among the Celtic Irish, they were said to worship “nothing but idols and impure things.”[9]

No Scripture

No evidence exists that suggests that the druids possessed any formal sacred written scriptures, such as the Bible. Writing on Druidism, Julius Caesar recounted that druids learned a large number of verses or saying, committing them to memory, which sometimes required up to twenty years to complete the course of study. From the fragmented remains of Druidism, it appears their faith and practices were passed on in oral rather than written form.[10]

Astrology and the Black Arts

Druids were well versed in astrology, magic, and the mysterious powers of plants and animals. As is true of much of the pagan world, their forms of worship were closely associated to prominent features of the natural world, often observing natural occurrences as signs concerning future events. Roman historian, Pliny the Elder, records the fact that the druids believed a waxing crescent moon, like the mistletoe, was an instrument of healing, and for this reason, Celtic goddesses are sometimes depicted wearing lunar amulets.

Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe

Holding the oak tree and mistletoe in great reverence, Druids customarily conducted their rituals in oak forests, where they commonly used stone altars. This place of worship (or natural temple) was called a dolmen. Though ancient writers do not provide evidence that the Celts and their druids believed in pantheism—that all was god(s)—they do provide images of forms of worship that are closely associated with nature.

The mistletoe was regarded as a cure for infertility and highly desirable.[11] Pliny the Elder, records the extraordinary lengths druids went to when collecting mistletoe and the rituals of worship related to its use:

The druids - that is what they call their magicians - hold nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and a tree on which it is growing, provided it is Valonia Oak.... Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on the sixth day of the moon....Hailing the moon in a native word that means 'healing all things,' they prepare a ritual sacrifice and banquet beneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whose horns are bound for the first time on this occasion. A priest arrayed in white vestments climbs the tree and, with a golden sickle, cuts down the mistletoe, which is caught in a white cloak. Then finally they kill the victims, praying to a god to render his gift propitious to those on whom he has bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe given in drink will impart fertility to any animal that is barren and that it is an antidote to all poisons.[12]

Human and Animal Sacrifices

From all indications, the Celts reflected a nearly universal conviction that souls of individuals do not perish at death. Julius Caesar indicates that the Celts practiced human sacrifice, often with criminals or enemies placed inside a wicker effigy of a man, then set ablaze, apparently with many humans encased within it. St. Patrick vigorously opposed the sacrificing of infants by the Irish Celts to harvest gods. Like Patrick and generations of Christians who preceded the life and ministry of Patrick, Christians in the present generation are likewise called upon by God to defend the unborn and weak. Christians are presently being called upon to save the lives of the unborn and redeem their cultures from the paganism that ostensibly gains more and more vitality daily.

The children's "counting-out rhyme," "Eeny, meeny, miny, mo," is a version of the Druid death chant, "Eena, mena, mona, my." It was used by the Druids to select victims to be ferried across the Menai Strait and burned alive in wicker cages as human sacrifices in the Beltane spring festival on the sacred Isle of Mona (now Anglesey).

The Celtic Irish were fierce warriors. In his ministry among the Irish, Patrick vigorously opposed long established practices relating to prisoners of war. Prisoners were often sacrificed and their skulls used as ceremonial drinking bowls. Today in many colleges and universities, “intelligent” professors ridicule missionaries for having "Christianized" pagan cultures around the world. Would it have more civilized, more humane for Christians to have neglected ethical concerns? The struggle between Christianity and paganism (in this case the form of Druidism) had begun many years before Patrick arrived in Ireland as missionary, and it continued many centuries following.

Samhain—The Beginning of Halloween

The Celts in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man annually observed four major festivals: Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh and Samhain . The last of these four events, Samhain, was observed from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1. October 31, according to the Celts in this corner of the British Isles, was the close of one year and November 1 the beginning of the new year. Activities pertaining to this festival may be roughly classified into two categories, though they are not mutually exclusive, but interrelated to each other.

The first category of activities associated with the celebration of Samhain related to the land, crops, livestock and well-being of the people. At this time of the year, cattle were brought back from summer pasture and livestock slaughtered for winter provisions. It was also a time of threshing and preparation of other foods for the winter. Naturally, this was a time of feasting and sharing, though overshadowed by yet another more sinister aspect of their celebration.

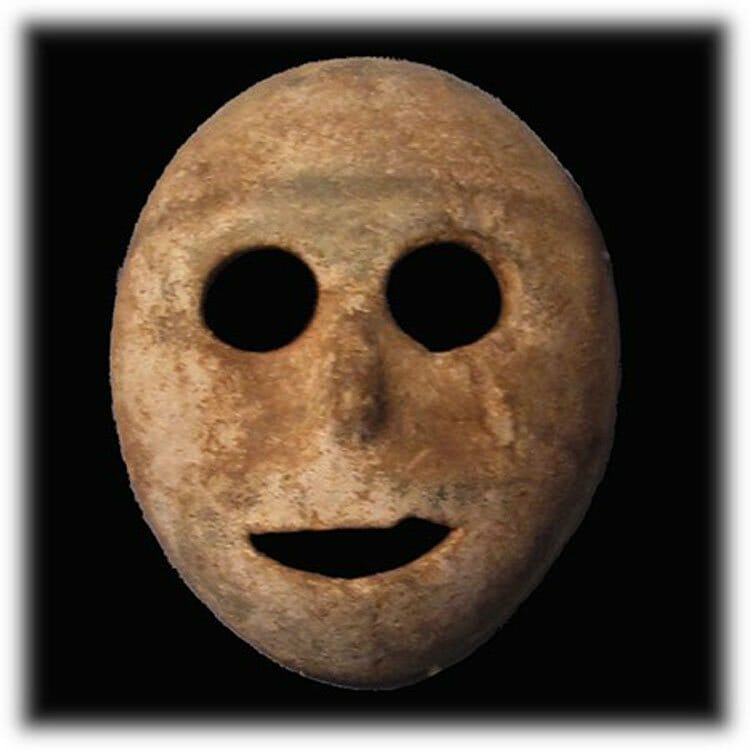

The second category of activities associated with Samhain was spiritual in nature. The Druid priest practiced divination rituals in an effort to determine the degree of fortune or misfortune that would be experienced in the coming year, often making their prophecies based upon numerous natural signs. Because Samhain was the beginning of the "dark part" of the year, spiritual darkness was also associated with it. It was believed that spirits or fairies were given greater liberty by spiritual forces to enter the realm of the living. Evil spirits were regarded as menacing figures that would steal infants, destroy crops, and kill farm animals. The Celts felt obligated to win the favor of these sinister spirits so that they and their livestock could avoid their fury and survive the winter. To placate these evil spirits, food and drink was left out for their consumption. In addition, the practice of dressing in grotesque costumes and appealing for treats throughout the neighborhood appears related to attempts to ward off evil spirits on one hand (resulting from much activity in the village) while deceiving the spirits by impersonating them on the other hand (making them believe they also were evil spirits). Pranks, similar to the mischief of spirits whose favor had not been won, were also performed, and to guide them on their rounds through the community, impersonators of the evil spirits hallowed out turnips, carved grotesque faces on them (to be more convincing to evil spirits) and illuminated them from within to make turnip jack-o-lanterns. Thus, the rise of trick or treat.

Accompanying this notion of the ease of movement for evil spirits at Samhain was also a belief that the spirits of departed family members would visit their kinsmen in search of warmth and good cheer as winter approached. The living beckoned the spirits of departed loved ones to return and a place was set at the family table for them. As was the case with the major festival in May (Beltane), special bonfires were lit and believed to possess special cleansing powers when accompanied by the druid rituals associated with them. These bonfires were attempts to ward off evil spirits and at the same time to guide home the souls of departed loved ones. This practice was the beginning of the practice of lighting candles and saying prayers for the dead.

The Celtic observance of Samhain (October 31-November 1) has come to greatly influence Christian observance of Halloween and of the larger three-day observance of Triduum of All Hallows (October 31-November 2; discussed above in the introduction). Following the Jewish custom of beginning to celebrate a holiday or special observance the day before the actual observance (on the eve), Christians began to also celebrate on October 31 in anticipation of the two special days that would follow.

All Saints' Day

The two days that have come to be celebrated on November 1 (All Hallows' Day or All Saints Day) and November 2 (All Souls' Day) required centuries to come to maturity in Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox traditions. Originally, All Saints' Day was first celebrated by the Greek Orthodox Church the week after Pentecost and may have been observed as early as the fourth century under the name, Sunday of the Martyrs .[13]

In the Roman Catholic tradition, this practice was introduced by Boniface in 609, but was originally observed in the month of May before it was rescheduled by Pope Gregory IV to November 1 in 834—the day of the Celtic Samhain celebration. Since the number of individuals designated by the Eastern and Western Churches as "saints" had proliferated to such an extent, it became too burdensome to dedicate a feast-day to each. For this reason, both the Eastern and Western branches of Christianity chose to commemorate all the saints on one day. All Saints' Day was introduced to England by 870 where it came to be known as All-hallowmas. Among the Anglican, Lutheran and Roman traditions, All Saints' Day continues to be observed on November 1.[14]

All Souls' Day

The observance of All Souls' Day on November 2 was a natural result of the celebration of All Saints' Day on November 1. It was first introduced by Odilon, abbot of Clugni,[15] who encouraged its observance among his reformed Benedictine monks beginning in 998. All Souls' Day soon spread to neighboring churches, promoting a day of prayer for the faithful or christened dead who were believed to be yet in purgatory. Prayers for souls in purgatory, as advocated by the Roman Church, assumed distinct features that continue to influence present-day observances of this season. In time, it became customary for individuals to dress in black and amble about towns and cities, each pealing out a mournful tone on his own bell to remind their hearers of the souls yet in purgatory. Another tradition that arose in parts of west England was the practice of "souling ."[16] Children and the poor walked door-to-door throughout their villages, saying prayers for the dead and singing as they went…

Soul! soul! for a soul-cake;

Pray, good mistress, for a soul-cake,

One for Peter, two for Paul,

Three for Them who made us all.

Soul! soul! for an apple or two;

If you've got no apples, pears will do,

Up with your kettle, and down with your pan;

Give me a good big one, and I'll be gone.[17]

Those who traveled the streets in this way were referred to as soulers and were given treats from the homes they visited, consisting primarily of fruits and small round cakes referred to as "souls ." Each cake eaten was believed to represent a soul being freed from purgatory.

Use of Costumes

Grotesque costumes had been used by the Celts in the observance of their Druidism to both ward off evil spirits and disguise themselves from the spirits. Among many Christians, costumes were also used as a means of disguise, but for a different reason:

It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints' Day, and All Hallows' Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes to disguise their identities.[18]

Impersonating the Saints

Early in the life of the Christian Church, pagan traditions were quickly assimilated into various portions of the Church, and at times, most of the Church had allowed itself to compromise biblical truth in favor or error. Pagan ancestor worship was one of the first errors Christianity faced. Lamentably, Christians began to credit to departed individuals the power of intercession with God. Those who had lived the most exemplary Christian lives—the saints—were believed to possess the greatest influence with God, and for this reason, Christians offered their prayers to the saints instead of God himself. The relics related to departed saints were placed on display during the Hallowmas season and special blessings were often promised for the veneration of these relics. In those towns and villages that were too small or poor to host a display of relics, a tradition arose which honored the lives of devoted believers by dressing like and impersonating them. Among some contemporary Christians, similar efforts have been used for the sake of appreciation rather than veneration or worship.

Use of Candles

Bonfires at this season of the year were used by the Celts to ward off evil spirits and direct the spirits of departed kin to their homes. It is no surprise that in countries such as Austria, England, and Ireland burning candles were placed in every room of a home to guide souls back to visit their earthly homes. These candles were referred to as "soul lights."

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

With the rise of the Protestant Reformation, Christian practices were increasingly held up to the authority of Scripture, not the traditions of men, the pronouncements of council, or pontification of any individual. As Justice Brewer writes, Christians are obligated to continue the work of Christianizing culture from a biblical perspective. Too many times, the civilizing influence of the Gospel has been diluted to appease the vain and vicious. With regard to those observances related to the Halloween season (October 31-November 2), several facts must be kept in mind as Christians seek to identify ways they can redeem culture:

First, Halloween celebrates paganism. It is evident from God's response to Aaron's golden calf (Ex. 32) that God does not permit his people to observe pagan practices. Let Christians earnestly look for creative, yet biblical, ways to celebrate the One true God.

Second, Halloween celebrates Satanism. Scripture clearly cites Satan and his demonic forces as the reality behind the occult (Deut. 32:16-17; Psm. 106:35-40; Acts 16:16-19; 1 Cor. 10:19-21; 2 Thess. 2:9-10; 1 Tim. 4:1). Let believers allow God to control Satan and the demonic world; human efforts to manipulate Satan and his forces are vain.

Third, Halloween celebrates fear. Rather than celebrating the peace that is spoken of in Scripture, Halloween glorifies fear (cf. 1 John 4:18). Let us emphasize the leadership of God's Spirit in the believer's life and the peace He brings.

Fourth, Halloween celebrates death. Jesus told his disciples that he came to bring life and to bring it more abundantly. Halloween, however, honors what Christ came to destroy (cf. John 10:10; 1 Cor. 15:56). Let the death of Christ and the life He brings to believers as a result be dominant themes in all we do.

Related articles . . .

[1] This book was the result of his lectures at Haverford College. Chapter two, "Our Duty as Citizens" (p. 45ff) is a challenge to Americans to continue the work of civilizing the nation through the advocacy of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. This book was an expansion of a Supreme Court case (Holy Trinity vs United States, 1892) in which Justice Brewer wrote the majority report declaring America to be "a Christian nation."

[2] This is also known as All Hallows' Evening.

[3] The difference between All Hallows' Day and All Souls' Day is where the departed are believed to reside. All Hallows' Day (All Saints Day) is a celebration of the lives of departed saints who are believe to be in heaven. All Souls' Day is a day of prayer for those who are believed to be in purgatory and who may be benefited by the meritorious efforts of those yet living.

[4] The Greeks coined this term and applied it to the uncivilized or anyone who was not Greek.

[5] The Celts of the British Isles were known as "Insular Celts."

[6] The exact origin of the term "druid" cannot be determined, but it is likely that it is derived from the Greek word for "oak tree." Greek, Irish, and Welsh history of this term is closely related to the idea of "oak-knower" or "oak-seer" as suggested by Pliny the Elder. Druid priest often performed their rituals under oak trees. "Druid," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druid, October 30, 2013).

[7] This appears to be the case in the following article: Matt Slick, "What is Druidism?" CARM: Christian Apologetic and Research Ministry (http://carm.org/druidism, October 31, 2013).

[8] "Druid," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druid, October 30, 2013).

[9] Skinner, Confessions of Patrick, 60.

[10] We cannot be completely certain that Druidism had no sacred writings. See, Matt Slick, "What is Druidism?" CARM: Christian Apologetic and Research Ministry (http://carm.org/druidism, October 31, 2013). Cf., "Druid," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druid, October 30, 2013).

[11] Mistletoe was also occupied a prominent place in Celtic art forms.

[12] Pliny, Natural History, XVI, 95; quoted in "Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritual_of_oak_and_mistletoe, October 31, 2013).

[13] Chrysostom (Homily 74 de Martyribus) indicates that it was known in the fourth century and was celebrated on Trinity Sunday.

[14] John McClintock and James Strong, eds., "All-saints' Day," Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature.

[15] Clugny is now Cluni, France. This was a group of reformed Benedictine monks.

[16] Souling appears to have spread beyond All Souls' Day to encompass the entire three-day observance (October 31-November2).

[17] John McClintock and James Strong, eds., "All-Souls' Day," Cyclopedia Of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature.

[18] Sorie Conteh, Traditionalists, Muslims, and Christians in Africa: Interreligious Encounters and Dialogue (Cambria Press, 2009); quoted in "Halloween," Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halloween, November 2, 2013).

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

Christianizing Halloween and Hallowmas

- 426

- 427shares