The Swiss Reformation

The cry for reform in the Western Church of Christianity preceded Martin Luther by centuries. Abuses and non-Christian practices crept into the Church and continued until the rise of the Protestant Reformation. Following the example of Luther in Germany, Huldreich Zwingli and John Calvin led the reform efforts in Switzerland. Like the reformation begun under Luther, the Swiss Reformation was part of the Magisterial Reformation because it attempted to work with the magistrates of the states of which they were a part. The following pages describe the rise of the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland and its influence beyond.

Table of Contents

Switzerland has proven to be the seedbed for many of the larger denominations that were birth by the Protestant Reformation. Within Switzerland, three significant Protestant movements were conceived, two of which merged to produce the Reformed Church. Those two traditions were birthed by Huldreich or Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) and John Calvin (1509-1564). In northern Switzerland, the German-speaking cantons followed the theology of Zwingli. In the French-speaking cantons of the south, Calvin held sway at Geneva. A third, and more radical form of thought, emerged in Anabaptism, the leaders of which initially worked with Zwingli in the northern cantons. The following is a brief discussion of the reformation, which occurred under Zwingli and Calvin, the latter being discussed under “The Radical Reformation.”

Huldreich Zwingli and the Reformation at Zurich

Zwingli ’s Early Life (1484-1506)

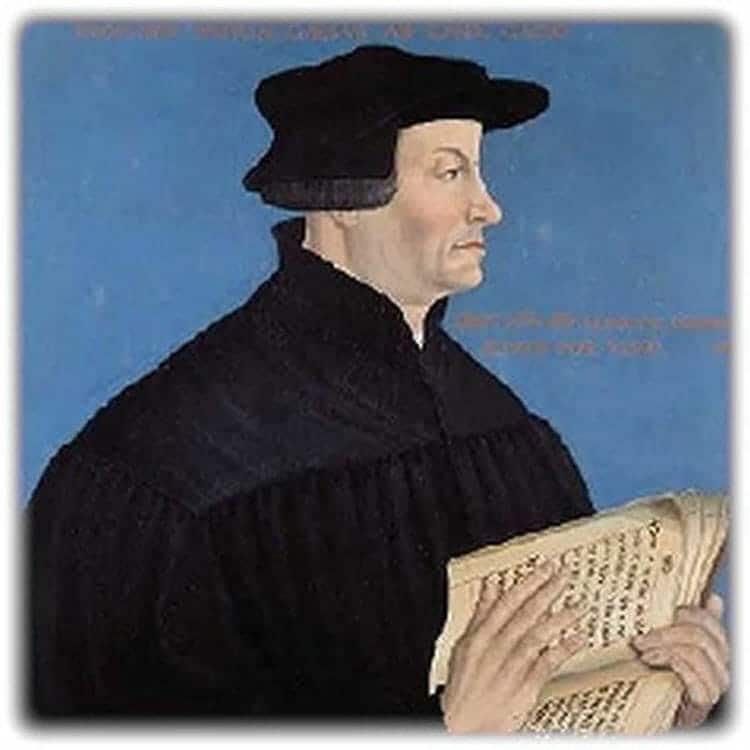

Huldreich (or Huldrych or Ulrich) Zwingli (1484-1531) was among the four major first generation Reformers. Zwingli and John Calvin were the Fathers of the Reformed Church.

Zwingli was born in Wildhaus (Toggenburg), an Alpine village in the canton of St. Gall on January 1, 1484. Though his parents were peasants, they were well-to-do people. Two of his uncles held offices in the church, one as deacon of Wesen and the other abbot of Fischingen. Zwingli himself was unusually gifted, both intellectually and musically. With such talents and familial influence, it is not surprising that he was destined for service in the church.

Education at Weesen, Basel, and Bern (1489-1498)

Zwingli was schooled in Weesen, Basel, and Bern from 1489 to 1498.

Student at Vienna and Basel (1498-1506)

Zwingli attended the University of Vienna from about 1498 to 1502, where he went through the common course of philosophy. While there, he acquired friendships with Vadian[1] (1484-1551) and Glarean[2] (1488-1563) and made the acquaintances of Faber[3] (ca. 1441-1502) and Eck [4] (1486-1543).

In 1502, Zwingli returned to Basel where he taught school, studied theology, enjoy close contact with Leo Jud, and listened to Thomas Wyttenbach. At the University of Basel, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1504 and his Master of Arts degree in 1506.

Pastor of Glarus (1506-1516)

From 1506 to 1516, Zwingli served as parish priest in the town of Glarus and accompanied Swiss mercenaries as chaplain. Here he learned Greek, studied Plutarch, Plato, and especially the Bible, copied the Epistles of Paul in order to have them always with him, read Origen, Chrysostom, Jerome, and Augustine, as well as more contemporary and incendiary figures such as Wyclif, Petrus, Waldus, Hus, and Picus de Mirandola, and entered into correspondence with Erasmus. His marked ability gained him a distinguished reputation. Several of significant dates emerge from the time of his pastorate at Glarus:

|

1510 |

The Poetic Fable About the Ox. |

|

1513 |

Accompanied Glarus Troops to Novarra |

|

1514-1516 |

The Labyrinth |

|

1515 |

Accompanied Glarus Troops to Marignano |

|

1516 |

Visited Erasmus in Basel |

Pastor at Einsiedeln (1516-1518)

Between 1516 and 1518, Zwingli served as pastor at Einsiedeln where he came to realize the abuses of the indulgence system. Einsiedeln, in the canton of Schwyz, was the most celebrated pilgrimage site in all of Switzerland. Pilgrims flocked to his town from all over Switzerland and southern Germany. Though he did not openly attack the indulgence system, he did not conceal the fact that he was painfully aware of the discrepancy between the allowances of the Church and the expectations of the Bible.

During his pastorate at Einsiedeln, Zwingli became more opinionated against the Church. In 1517, he began to discuss with friends the possibility of abolishing the papacy. In 1518, he drove the indulgence-seller, Samson, out of the Schwyz canton with his public denunciations. Zwingli’s superiors in the Church hope they could come the gathering storm by making him titular[5] chaplain to the Pope. But, in December 1518, Zwingli accepted a call as preacher to the cathedral of Zurich.

People's Priest at Zurich (1519-1531)

On New Year’s Day, 1519, Zwingli became the people's priest at Zurich Great Minister. From what may be understood about this period in Zwingli’s life, it appears that Zwingli came into contact with Lutheran thought and experienced a personal conversion the same year he began his ministry at Zurich.

A. Movement Toward Reform (1522)

His biblical preaching commended him to his parishioners, with peasants crowding into the cathedral when he preached on market-days. His influence grew to such an extent that by 1521[6] he was able to prevent Zurich from entering with other cantons into an alliance with France. Here he began to oppose the practice of enlisting the Swiss as mercenaries. It appears to have been his resistance to the alliance with France that gained him more enemies than those who opposed his moral and religious views. Opposition forces were successful in forcing the Bishop of Constance to send his vicar-general to Zurich to try to subdue Zwingli . In debate, the vicar-general was greatly out defeated. This event incited Zwingli to publish his first tract that was decidedly sympathetic toward reform (April, 1522).

Ecclesiastical authorities moved to quickly suppress Zwingli ’s reform efforts. But in July 1522, Zwingli convened a meeting with ten other pastors of Zurich. From this meeting came an address to the Bishop of Constance and the magistrates of Zurich that demanded freedom of the pulpits, but also the abolition of celibacy. Zwingli became the dominant reformer after Luther’s mysterious disappearance after the Diet of Worms. Among those with whom Zwingli was in contact that this time were Capito, Hedio and Bucer in Strasbourg, Pirkheimer and Durer in Nuremberg, and Nesen in Francfort, to name only a few.

|

1522 |

March 9 |

"Sausage Meal" at the home of Christoph Frowschauer. By 1522, the citizens of Zurich were eating meat during Lent and changing the practice of Roman worship. |

|

April 7-9 |

Disputation with episcopal delegation | |

|

April 16 |

Regarding the choice and the Freedom of Food | |

|

July 21 |

Disputation with mendicant monks | |

|

August 22-23 |

The First and Last Word | |

|

September 6 |

Regarding Clarity and Certainty of the Word of God | |

|

September 17 |

A Sermon About the Eternally Pure Maid |

B. Zwingli Wins Two Disputations (1523)

The fermentation in Zurich reached such a fever pitch that the magistrates decided a religious disputation. On January 29, 1523, with about six hundred persons present, Zwingli debated these new practices with Johann Faber in an attempt to persuade city magistrates of the validity of Reformation thought and practice. For the occasion, Zwingli had drawn up Sixty-seven Articles that maintained the vanity of apparatus and scheme of the Church of Rome, the supremacy of Scriptural authority, and the sufficiency of Christ’s atonement for sin. An original feature of the theses was the principle of ecclesiastical polity. Zwingli believed that the congregation, not the hierarch, possesses the right to consider the discrepancies that may arise in matters of doctrine and practice. He further asserted that the administration of the Church belongs to state authorities, but if the authorities of the state went beyond what is allowed in Scripture, they were to be deposed. The town council of Zurich decided completely in Zwingli's favor, and his ideas soon won wide acceptance. Zwingli was vindicated of the charge of heresy and his Sixty-seven Articles, drawn up for the debate, became the first Reformed confession of faith. A second disputation was held October 26-28 to consider the issue of the use of images.

Questions continued to plague the progress of the reform in Zurich. The second disputation decided that images were forbidden in Scripture and that the mass was not a sacrifice as taught by the Catholic Church. In addition, a number of festivals, processions, and ceremonies were abolished. The appearance of the Anabaptists at Zurich at the time of the second disputation further escalated the difficulty of the advancing reform.

|

1523 |

January 29 |

First Zurich Disputation |

|

July 14 |

Analysis and Reasons for the Concluding statements | |

|

June |

Female convents in the city and country were closed by the magistrates and the nuns were returned to their homes | |

|

July 30 |

Regarding Divine and Human Righteousness | |

|

August 1 |

Little Textbook | |

|

September 29 |

New regulations for the Great Minster | |

|

October 26-28 |

Second Zurich Disputation | |

|

November 17 |

Short Christian Introduction |

C. Zwingli Placed Under Ban; Marriage (1524)

The pressure of the Roman Catholic Church against the reforms at Zurich intensified in 1524, being mediated through the Swiss Union. At a diet in Lucerne, January 26, 1524, the united canton decided upon sending an embassy to Zurich warning the city not to deviate from time-honored traditions. On March 21, Zurich answered saying it would not allow outsiders to interfere in matters of spiritual care. That same year a new embassy, July 12, threatened Zurich with exclusion from the union, and she began immediately to prepare for war. An invitation was extended to Zurich and Zwingli to attend the great disputation at Baden, but Zwingli’s safety could not be ensured, so the invitation to confront Eck and Faber at Baden was rejected. The diet placed Zwingli under the ban.

|

1524 |

January 13-14 |

Disputation with traditional canons |

|

April 2 |

Zwingli entered into a secret marriage with widow Anna Reinhard | |

|

April 8 |

Alliance of the five statues in Defense against the Reformation | |

|

June |

Removal of pictures and statues from Zurich churches | |

|

October 24 |

Dissolution of the Mary Minister | |

|

November |

Letter to Matthew Alber Regarding the Lord's Supper | |

|

December 28 |

Whoever Causes Unrest |

D. Views on Sacraments and Predestination (1525)

1. The Sacraments as Pledges

By 1523, Zwingli ’s teaching on the sacraments was near Luther’s. He believed the sacraments were signs or pledges of God’s promises and faithfulness to his people: “God has instituted, commanded and ordained with his word, which is as firm and sure as if he had sworn an oath to this effect.”[7]

But by 1525, Zwingli 's understanding of the sacraments (the Eucharist and baptism) came to represent not only God's pledges of faithfulness to the believer, but also the believer's pledge of loyalty to other believers. Drawing upon his experience of military chaplain, Zwingli came to believe that participation in the sacraments was a pledge of faithfulness to the Christian community. Zwingli eliminated Luther's idea of "the real presence" of Christ in the Eucharist .

Zwingli 's ideas of the sacraments were influenced by a circulating letter on the Eucharist drawn up by Cornelius Hoen (Hoehn).[8] Hoen contributed to Zwingli's understanding of the sacraments in two ways. First, Hoen suggested that the Eucharist was a pledge, like a wedding ring given by a groom to his bride to assure her of his love. Second, Hoen believed the Eucharist was also a commemoration, designed to "remember" Christ in his absence.

Concerted efforts at reform efforts were divided in late part of the year 1524. This period brought Zwingli into conflict with Luther over the subject of the Lord’s Supper. Carlstadt ’s exposition of the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper occasioned the dispute with Zwingli responding in an address on November 16, 1524. Tensions swirled around the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper until the Marburg Conference in 1529, following which time the controversy subsided for a time. By November and December of 1524, Zwingli was promoting Hoen's understanding of the Eucharist, and in 1526, he published his treatise, On the Lord's Supper. He suggested the Eucharist should be celebrated three or four times a year. By 1525, the reformation in Zurich was completed when the mass was abolished. Easter 1525was the first time that the Lord’s Supper was celebrated in the Reformed manner, with a white spread table instead of the altar and the laity partaking of the cup.

The Reformation in Zurich was established through gradual and peaceful means. Under the influence of Zwingli, the influential city of Bern, along with other cities, were also won over to Protestant thought and practice soon after Zurich looked favorably upon Zwingli.

2. Predestination

Prior to the time of Augustine, the Church Fathers unanimously endorsed the idea that the divine decrees of God concerning a person’s salvation were conditioned upon that person’s faith and obedience. Augustine’s controversy with Pelagius changed the way in which a portion of the Church regarded the divine decrees from that point forward as being completely dependent upon the bare will of God. Augustine taught the unconditional salvation of those whom God had chosen (single predestination), but he did not advocate unconditional reprobation (double predestination).

It was heterodox theologian Gottschalk (ca. 804-ca. 869) who first advocated the unconditional salvation of the elect and the unconditional condemnation of the reprobate. Gottschalk was first condemned by the Synod of Mainz (848) and then by the Synod of Quiercy (849) after which he was deprived of his monastic orders and sentenced to imprisonment.

Within the Reformed tradition, the fountainhead of the doctrine of predestination is Zwingli . Zwingli assumed his ministry at Zurich on January 1, 1519. That August, a plague seized the town and laid its hand upon Zwingli himself. He resigned himself to the providence of God, and from this experience, Zwingli ostensibly developed his doctrine of God’s absolute sovereignty.

The origin of this doctrine in Zwingli ’s thought and its relation to paganism may be deduced from his sermon De providentia, “On Providence” (1519). Throughout De Providentia, Zwingli refers to Seneca’s fatalism.[9] Under this influence, Zwingli argues that whether an individual is saved or condemned is totally dependent upon God, who freely makes this decision from eternity.

This view of the omnipotence of God and the impotence of man created a fisher between Zwingli and other humanists who affirmed naked human ability in salvation. The following year (1525) Zwingli responded to Erasmus denying the idea of liberum arbitrium (free will) which Erasmus had defended the previous year (1524). Many of the humanists who accepted human ability in the reformation of character and moral life broke with the reformers from this point forward.[10]

|

1525 |

January 15 |

Welfare laws |

|

January 17 |

Disputation with opponents of infant baptism | |

|

January 21 |

First adult baptism | |

|

March |

Commentary About the True and False Religion | |

|

March 26 |

The Shepherd | |

|

March-April |

Act or Custom of the Supper | |

|

April |

Appointed school supervisor | |

|

April 13 |

Revision of the Eucharist celebration | |

|

May 10 |

Marriage laws | |

|

May 27 |

On Baptism, Anabaptism, and Infant Baptism | |

|

June 19 |

“Prophecy" opens | |

|

August |

Council mandate for political and economic reorganization |

E. Quiet Years (1526-1527)

The years 1526 and 1527 were quieter years for Zwingli and Zurich. However, these years were the lull before the storm. In 1527, a synod of Swiss evangelical churches was formed in an attempt to mutually support each other.

|

1526 |

February |

A Clear Briefing About Christ's Supper |

|

May 19-June 9 |

Baden Disputation | |

|

1527 |

July 31 |

Refutation of the schemes of the Anabaptists |

|

December |

Fortress Law alliance of Zurich with Constance |

F. Prominent Cities Accept Protestantism (1528)

By the end of the 1520s, the Reformation had laid claim to other prominent cities of the Switzerland. At the conference of January 4, 1528, attended by Zwingli himself, the city of Bern was gained for the Reformation. Soon after, Basel, St. Gall, and Schaffhausen followed Bern’s example.

|

1528 |

Fortress Law alliance of Zurich church regulations | |

|

January 6-26 |

Bern Disputation | |

|

February 7 |

Reformation laws in Bern | |

|

April 21 |

Reformation laws in Basel |

G. War Averted; Marburg Colloquy (1529)

In November 1528, five Roman Catholic cantons, lead by Freiburg, composed a separate alliance (Christian Union of Catholic Cantons), and in the spring of 1529, the Archduke of Austria, Ferdinand, became a member of the alliance. The alliance between Swiss union members and a foreign power was formally protested by Zurich, St. Gall, and other on April 21 and received a chilling response. One month later on May 29, a Protestant pastor from Zurich was captured by the Union, carried to Schwyz, tried for heresy, and sentenced to be burned. Zurich immediately responded by declaring war and moving troops into position for war according to a plan devised by Zwingli himself. Zwingli stood with the bulk of the army at Kappel, but before the battle could begin, mediators were able to devise a plan of peace, negotiated June 26.

Tensions had arisen in earnest between Protestants by the end of 1524 and 1525 over the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. For several years those tensions prohibited Protestants from cooperating with each other. But in October of 1529, through the efforts of Landgrave Philipp of Hesse, a conference was convened at Marburg to explore the possibilities of greater cooperation among Protestants. Though they were able to agree on a variety of points, Luther and Zwingli were unable to agree on the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper.

|

1529 |

Fortress Law alliance of Zurich with Basel, Schaffhausen, Biel, and Muhlhausen | |

|

April |

Reformation laws in Basel | |

|

April 22 |

"Christian Union" of Five States with Ferdinand I | |

|

June 26 |

First Kappel Peace Treaty | |

|

September |

Reformation laws in Schaffhausen | |

|

October 1-4 |

Marburg colloquy between Luther and Zwingli |

H. Zwingli on Justification (1520s)

Often the doctrine of justification among the Magisterial Reformers is treated as a homogeneous phenomenon. So sweeping an interpretation of the Reformers on this subject often masks the differences that existed. The Lutheran Reformation, being influenced by the individualistic tendencies of the humanism of the Renaissance, tended to focus upon the individual and ask, “How can the individual be made right before God?” The Swiss Reformation was initially less concerned about the interests of the individual and was more preoccupied with the claims of the community. For this reason, the Swiss Reformers were initially more concerned with the moral consequences of the faith and less concerned the doctrine of justification by faith.

Zwingli believed the greatest affect of the Reformation was upon the church and society, and not the individual.[11] He was primarily concerned with the import of the New Testament upon Zurich and was not concerned with how the individual fulfilled the demands of a righteous God. Zwingli regarded more highly the moral example of Christ over any consideration of the significance of Christ’s presence in the believer.

One must be careful not to believe that Zwingli taught justification by works, as if human ability was in any way capable of evoking a grace from God that would lead to salvation. During the 1520s, Zwingli’s understanding of justification fell more and more in line with Luther’s teachings on the subject, though Zwingli’s teachings never paralleled Luther’s. Whereas Luther believed that Scripture was primarily concerned with the articulation of the promises of God concerning justification and salvation, Zwingli regarded Scripture as the vehicle through which God has communicated his moral demands for believers. Zwingli saw Scripture as the establishment of the moral norms of the believer in response to the example of Christ.[12]

I. A Quiet Year (1530)

|

1530 |

July 3 |

Account of Faith |

|

August 20 |

Remembrance of the Sermon About God's Providence | |

|

November |

Alliance between Zurich and Hesse |

J. Zwingli Loses His Life at Kappel (1531)

In 1531, Zwingli, against the treaty of Kappel (1529), attempted to force reform in some cantons. The result was war between the Catholics and Zwinglian Protestants. On October 10, 1531, the army of the Catholic cantons stood on the frontiers of Zurich. The following morning Zwingli took the field as a chaplain with his soldiers and met the Catholic forces, once again, at Kappel. The Protestants of Zurich were utterly routed by the Catholic army. Zwingli bent over a dying man to comfort him and was hit with a spear. Realizing that death was near, Zwingli triumphantly proclaimed, “They can kill the body, but not the soul.” Zwingli's was succeeded in leadership by Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575).

|

1531 |

May |

Food blockage against the Five States |

|

July |

Zwingli offered to resign; Exposition of the Christian Faith. |

John Calvin and the Reformation of Geneva

I. Calvin's Early Life (1509 to April 1538)

John Calvin was born at Noyon, France, about seventy miles northeast of Paris, on July 10, 1509. He had four brothers and two sisters.

Upon going to the University of Paris in 1523, Calvin attended a short time at College de la Marche, where he studied grammar and rhetoric under the humanist Mathurin Cordier and began a lifelong friendship with him. Soon Calvin transferred to the College de Montaigu for theology; here he was introduced to (as was Luther) the scholastic nominalistic theology (the Pelagian, via moderna) under John Major and apparently undertook the study of the early Fathers, especially Augustine.

It was in these formative years that Calvin became acquainted with the Cop family and formed a close association with a humanist cousin, Pierre Olivetan, who had already been influenced by Lutheran teaching.

Calvin's father sent John to Paris to prepare him for a career in divinity. It was under the influence of Maturin Cordier that Calvin was first encountered with humanism while at the College de la Marche. Later Cordier would join Calvin in Geneva and shape the young scholars there as he had Calvin in Paris. While in their formative years, Calvin also came under the humanist evangelical influence of Jacques Lefevre d'Etaples and Bishop Briconnet.

In the College de Montaigu, Calvin received his first dose of scholastic education under the influence of Scotsman, John Major. Calvin was greatly influenced by Aristotelian natural philosophy at Paris; later he developed distaste for medieval scholasticism. He seems to have accepted Aristotle's natural philosophy.

Also, it appears that nominalism left its mark on Calvin's mind; that is, the denial of universal in support of the particular. However, McGrath believed that there were two nominalist schools of influence at the time of the Reformation; the via moderna (modern way) tended toward a Pelagian position while the schola Augustiniana moderna (modern Augustinianism school) toward Augustinianism. Though it is not known for certain, it is very possible that Calvin was influenced while in Paris by the latter nominalist school.

Luther's influence was sensed in Paris as early as 1519 as a result of Luther's debate with Johann Eck of this year. The University of Paris found itself wrestling with the problems that were being created by Luther as early as 1520. However, Luther was condemned in 1521. Luther's ideas seem to have gained a wide hearing during Calvin's stay at the University of Paris.

A. Study of Law in Paris (1528)

Upon receiving his Master of Arts degree at Paris, Calvin traveled to Orleans and Bourges to study law. It appears that while he was here he continued to pursue humanist interests, learning Greek from a German Lutheran scholar, Melchior Wolmar. While studying law at Orleans and Bourges, Calvin came in contact with a circle of Protestants.

Calvin appears to have received much of his philological influence from Guillaume Bude who was a legal humanist, while at Orleans. From him, Calvin learned to approach a text, interpret it within the linguistic and historical context, and apply it to the needs of the present day. It is this method that Calvin used in his commentary on Seneca's De clementia.[13]

B. Study of Law at Orleans (1528-1529)

Calvin left Paris for the University of Orleans to study of law between 1528 and 1529. A professor of Roman law seems to have impressed Calvin with Italian humanism as no one else had. Alciat was that professor; it was at Bourges that Calvin came into contact with him.

C. Return to Paris (1531)

Following his father's death, Calvin returned to Paris where he continued his literary studies. He began to study at the College de France where he continued his study of Greek with Pierre Danes and study of Hebrew with Francois Vatable.

D. Return to Orleans (1532)

In 1532, Calvin returned to Orleans for a short time to complete his law degree and he published his commentary on De Clementia, which demonstrated his humanistic interests. Calvin's style in this work evidences the method of Valla, Erasmus, Bude and others.

Calvin published, with his commentary, Seneca's De Clementia (On Mercy). This work demonstrates Calvin's ability in Latin, belief in moral education, and devotion to antiquity. At this point in his life, he was committed to reform, but not to the point of doctrinal dispute. He most likely was a moderate Fabrisian reformer prior to his conversion.

As early as 1532-33, Protestant missionaries from Berne had begun to make their way into the city of Geneva. Guillaume Farel was among the most famous of these missionaries and would later implore Calvin to remain in the city to help with Protestant reform efforts.

E. Sudden Conversion (ca. 1532-1534)

Sometime between the summer of 1532 and the spring of 1534 Calvin underwent a "sudden conversion" and embraced the doctrines of the Protestant reformers. This experience he would later describe in his commentary on the Psalms in 1557.

F. Flight from Paris (November 1533)

In October 1533, a friend of Calvin's, Nicholas Cop, was elected rector of the University of Paris this year. It is believed that Calvin helped Cop prepare an inaugural address for him on Christian philosophy. Cop delivered the address on All-Saints Day in 1533, November 1.[14] As a result, Calvin and Cop were forced to flee the city—Calvin fleeing into southern France. Prior to this, the King of France attempted to tolerate reform movements that seemed to reflect Lutheran movement in Germany, but suddenly broke with his tolerant spirit. Calvin seems to have returned to Paris a short time later, in December.

G. First Theological Work, Psychopannychia (1534)

In his first theological work, Psychopannychia, Calvin refuted the Anabaptist doctrine of the sleep of souls between death and the resurrection (1534). This work was probably printed at a later date. It is important to realize, that Calvin was not anxious to break with the Church and made no attempt to write against it. However, in May of this year he did resign the chaplaincy in Noyon, which may be interpreted as a break with a corrupt unevangelical church; this is only a conjecture, however. We may conjecture that his conversion occurred shortly beforehand. It was in 1534 that he surrendered his ecclesiastical benefits. Upon conversion, he seems to have come to believe that there was a radical difference between humanism and its philosophy and that of the Christian faith; rather than asserting the humanistic emphasis of man's greatness, Calvin now emphasized man's sinfulness. Even Christian humanists had impersonal notions of sin, but now that would change—sin became very real to Calvin. What he did learn from humanism was a method. Previously he saw this as an end in itself, but now he saw it as a means to an end.

H. Travel in France and Italy (1534-1536)

From the summer of 1534 to the spring of 1536, Calvin traveled in France and Italy (and to Basle), in part because he had become associated with reform efforts. On October 18, 1534, placards placed in prominent places throughout France that denounced the Catholic mass and extolled evangelical interests. This prompted King Francis I to initiate vigorous prosecution of all those suspected of evangelical sympathies. Because of the increasingly hostile environment, Calvin left France and fled to Basel in January of 1535. Basel was a city that had already demonstrated sympathy toward humanism and evangelical proponents. The University at Basle had once been a center for humanist studies. Here Calvin first published his Institutes in Latin while only twenty-seven.

In 1536, the King needed every individual he could raise in his war against the emperor; as a result, amnesty was granted for French religious exiles. He returned to Paris to settle some business and then set out for Strasbourg, but was detoured to Geneva.

Early Years at Geneva (1536-1538)

While Calvin stayed in Basle (1535), he came to an awareness of the persecution of the evangelicals in France. The evangelicals seem to have been identified with the radical Anabaptist movement and accused of creating great disruption. Calvin appears to have published his Institutes for the purpose of clarifying what an “evangelical,” was. After this, he set off for the Italian city of Ferrara where other evangelicals had found haven in the court of the Duchess of Ferrara. From here, he returned to Basle and then to France for only a short time.

On July 1536, he left France and set off for Strasbourg leaving behind the perils of France. However, the road to Strasbourg was threatened by the movement of troops in the war between Francis I and the Emperor. As a result he decided to stay one night in a city that he was passing—that city was Geneva. On August 5, Calvin arrived at Geneva, Switzerland, intending to stay over night. But because of the appeal of William Farel, Calvin remained in Geneva.

I. Calvin’s Reforms in Geneva (January 1537)

In January 1537, Calvin submitted his memorandum on church government to the city council of Geneva. Soon after, a Confession of Faith and a Catechism followed.

J. Forced into Exile (April 1538)

In April 1538, the city councils of Geneva passed into the hands of those who were less sympathetic to the severity of Calvin and Farel's reforms. As a result, they were forced to leave the city.

Exile to Strasbourg (1538-1541)

While exiled from Geneva (April 1538-September 1541), Calvin ministered at Strasbourg to a French congregation and continued his studies.

K. Influence of Bucer on Calvin

In 1900, the influence of Martin Bucer on Calvin became a matter of serious consideration. Even before Calvin met Bucer, there was correspondence between the two men. Calvin had probably read Bucer's commentary on Matthew and John. While at the Synod of Bern in 1537, Calvin submitted a confession of faith of the Eucharist that reflected Bucer's point of view. In this, he rejected Christ's local presence in the elements while asserting the communion of the body and blood of Christ as well as in his spirit. Against Luther, Calvin and Bucer were in harmony with regard to their views on the Eucharist. Both Calvin and Bucer believed that their position represented the mediating ground between Luther and Zwingli .

The relationship between Bucer and Calvin can be seen more clearly in Calvin's Institutes. It is likely that by 1536 Calvin had read Bucer's commentaries on the Gospel and had employed some of Bucer's exposition in the Institutes of that same year. The edition and translation of 1539 and 1541 even more clearly indicate dependence upon Bucer's third edition of his commentaries on the Gospels and his newly published commentary on Romans. The doctrine of predestination is the point of contact between the two men. It is very likely, however, that Calvin and Bucer both were being informed by a third party—Augustine. It does not appear that Bucer did inform Calvin's understanding of predestination as glorifying to God. They shared similar views in other areas such as the validity of the Law, equality of the two Testaments as expressions of Divine will, and repentance.

With regard to the nature of the church, Bucer is more clearly reflected in Calvin. The emphasis upon the visible and invisible church could have been derived from Augustine, but the Calvin's source for his doctrine of the visible church was clearly taken from Bucer. Also, the theory of the four ministries of the church was accepted by Calvin, something that had been espoused by Bucer. Bucer also guided Calvin with regard to ecclesiastical jurisdiction for the sake of the cure of souls. Yet it must be admitted that Bucer did not subjugate Calvin or dominate Calvin's thought to the point that he was unable to distinguish his own personality in his thought—it was not servile imitation.

L. Works of 1539

Several important works of Calvin's appeared in 1539:

1. The 1539 edition of Calvin's Institutes reflects the influence of Bucer.

2. His commentary on Romans.

3. His Epistle to Cardinal Sadoleto who was trying to retrieve Geneva from the clutches of the Reformation on behalf of the Roman Church.

4. And other smaller works . . .

M. Marriage (1540)

Calvin married and in the ensuing years fathered one child and supported his wife's two children that were part of her previous marriage.

N. Friendship with Melanchthon (1541)

At the Diet of Ratisbon in 1541, Calvin formed a friendship with Philip Melanchthon .

O. French Edition of the Institutes (1541)

Calvin used French to communicate his message to a larger audience, as was the practice among the reformers in order to be able to address the common people. Because of his French publications, he is credited with having refined the language. The first French edition of the Institutes appeared in 1541 as was targeted for suppression by the parliament in Paris in 1542. Some scholars regarded the Institutes of 1536 as a catechism. It may be that the Institutes were modeled after Luther's smaller catechism. The second edition in 1539 demonstrates that it is no longer a small volume, but is now three times as large as it was in 1536; it is becoming a definitive statement of the Christian religion. Calvin intended the second edition to be a guide to Scripture for students of sacred theology. Editions in 1543 and 1550 in Latin continued to expand, but they were flawed in that they were poorly organized.

Return To Geneva (1541-1564)

In September 1541, at the invitation of the citizens of Geneva, Calvin returned to that city. From this time on, Geneva was Calvin's home and parish.

P. New City Constitution (November 1541)

In November 1541, Calvin submitted a new constitution to the city council of Geneva known as the Ecclesiastical Ordinances (1541) which, with some modification from the city council, provided the ground work for Calvin's church-state relationship and established the future polity of the Calvinistic churches. It provided for four ministries (pastors, teachers, elders, and deacons), and for a consistory constitute of pastors and laymen (elders). In 1542, it was supplemented with a new liturgical formula. Calvin believed the Ecclesiastical Ordinances (1541) gave him authority to exercise ecclesiastical discipline. But in 1553, the city council began to encroach on Calvin's authority that prompted him to offer his resignation, but was refused by the council.

When Calvin did return to Geneva, his ministry was marked by continued struggle with the city council. His reforms are believed to have been resisted more than is commonly believed. Calvin, however, was not as vicious as he is portrayed by some historians. Calvin's wife died in 1549 after much suffering. It seems that he was largely without the support of the power structure of the city until 1555. From 1541-1559, Calvin's status in the city was that of "habitant." He was not able to vote nor stand for office. His only opportunity to exercise influence was through preaching and consultation—he had no civic jurisdiction. This picture of Calvin is far different than usually received.

The most controversial aspect of Calvin's system of church government that he devised upon his return to Geneva was the Consistory. This institution came into being in 1542. It was composed of twelve lay elders and pastors (pastor's number continued to increase). The Consistory was to meet weekly, on Thursdays, in an effort to maintain ecclesiastical discipline. The Consistory was in effect an ecclesiastical court designed to preserve religious orthodoxy. It was designed to deal with those who posed a religious threat to Geneva.[15]

The tension between the city council and Calvin and his Consistory continued to grow. In November of 1553, the council overturned the ruling of Calvin's Consistory regarding an excommunication of a man. Calvin protested the council's interference with ecclesiastical discipline but the decision of the council was sustained by the Council of Two Hundred. In 1555, many who had fled to Geneva's safe haven were granted citizenship and allowed to vote. With this move, the balance of power was tipped in Calvin's favor in relation to the city council and with this came much rest to Calvin's ecclesiastical concerns.

There is an important development that should be mentioned. There is a development in Calvin's thought with regard to the ministries in the church:

Institutes—Calvin speaks of pastors and deacons.

Articles of 1537—Calvin mentions only one order, pastors.

Ordinances of 1541—four ministries: pastors, teachers, elders, and deacons.

Q. Calvin’s Catechism (1542)

The catechism was very important to Calvin, along with discipline in the church. Calvin's 1542 Catechism drew inspiration from Bucer's Catechism of 1534. Children were to recite the contents of the Catechism before being admitted to Communion. Following Bucer, he wrote the catechism in the form of a dialog. The catechism of 1542 was to a large degree responsible for the spread of Calvin's thought. Also, it became the basis of the Heidelberg Catechism[16] that became the typical catechism of the Reformed Churches.

From 1542, Calvin engaged in a diligent literary attempt to propagate his ideas—something that continued until his death. A staff of collaborators was at his disposal, which most likely was gathered from among the Protestant refugees who fled to Geneva.

R. Trouble with the Perrin Family (1546ff)

A former supporter of Calvin's, Ami Perrin, became increasingly dissatisfied with Calvin's ecclesiastical reforms and continued to cause problems until the mid-1550s. In 1548, Calvin's supporter lost in elections in the city of Geneva. As a result, Calvin had to labor for the next six years with the Perrin family in control of major political bodies. In the mid-1550s, after Calvin's supporters gained control of the city councils, Perrin, fearing for his life, fled to Berne. Four others who had opposed Calvin were not as fortunate. They were arrested and subsequently beheaded.

S. Executions at Geneva (1547-1553)

Among some of Calvin's opponents at Geneva who were executed after torture were, Jacques Gruet (1547), Raoul Monnet (1549), and Michael Servetus (1553) who was burned to death for his heretical views on the Trinity.

T. Formation of the Reformed Church (1549)

Calvin attempted to reconcile differences with the Lutherans and the Zwinglians . For nearly ten years, proposals and documents were circulated among the groups until 1549 when an article of agreement was established between them. But a war of pamphlets ensued between the Calvinists and Lutherans that only divided and fragmented their fellowship. But much greater success was achieved with the Zwinglians. In Zurich, Heinrich Bullinger, the successor to Zwingli, signed a formula of faith with Calvin that paved the way for the general acceptance of Calvinism throughout the Swiss cantons and birthed the Reformed Church (1549). In 1566, the Second Helvetic Confession was drawn up by Bullinger who relied very heavily upon Calvin’s thought and was, with the exception of two, accepted by all the cantons.

U. Doctrine of Justification (1540s-1550s)

1. Martin Bucer’s Double Justification

In a series of writings developed in the 1530s, Martin Bucer developed a doctrine of double justification that was an attempt to contribute to Luther’s single justification. Bucer argued that there were two stages in justification. The first justification referred to the gracious act of God that forgave the sinner of his sins. Subsequent generations of Protestants came to refer to this stage merely as “justification.” The second justification Bucer termed “justification of the godly,” which consisted of the believer’s obedient response to the moral law of God as evidenced in the example of Christ. For Bucer, an individual neither came to Christ initially under his own power, nor did he enjoy the subsequent experience of the second justification without the assistance of the Holy Spirit. With both the first and second justifications, God was believed to be mediating his grace to the penitent through the Holy Spirit.[17]

2. Calvin on Justification

On the doctrine of justification, Calvin’s teaching on the subject gained the ascendency in the Reformation as Calvin grappled with the doctrine in the 1540s and 1550s. His view mediated between Luther’s alien righteousness that was never imparted to the repentant sinner and Bucer’s view that justification causes moral renewal.

Calvin advocated the idea that faith united the believer to Christ through a mystical union that produced a twofold effect. First, that union with Christ results in a sinner’s justification. This justification was a declaration of righteousness in the sight of God. Second, this union with Christ resulted in the believer’s progressive regeneration or sanctification. Calvin differed from Bucer at this point, arguing the union with Christ was the basis for regeneration, not the sinner’s justification as Bucer had argued. For Calvin, union with Christ resulted in justification and regeneration.

V. Calvinism Spreads (1550ff)

Luther's influence over Europe, including Scotland and England, began as early as the 1520s, but seems to have reached its climax soon after his death in 1546. During this period, there was only a choice between Lutheranism and Catholicism. In the 1550s, Calvinism began to exert an influence upon many parts of Europe. It was during this time that Calvinism entered both England and Scotland.

Throughout the 1550s, Calvin engaged in polemical disputes with the Lutherans and Italian anti-Trinitarians.

Upon returning to Geneva in 1541, Calvin never traveled to his native France again. Up until about 1541, the evangelicals of France saw no differences between Lutheranism and Catholicism that could not be bridged. However, Calvin became an influential force that drove a wedge between Protestantism and Catholicism. In 1540, Calvin began to provide advice to evangelicals at Rouen. This practice continued to escalate in the years that followed. Calvin's works made their way to Paris in the 1540s where they were banned. Yet the demand for these works was high and government officials found it very difficult to prohibit their spread. Calvin's influence climaxed in France in the 1550s. As a result of the distribution of Calvin's writings, 684 were tried for heresy in France. Calvin's greatest impact appears to have been upon the middle class artisans. Calvinism appears to have sustained little impact upon the peasants.

In April of 1555, preachers were sent into France to spread the Calvinistic cause. The city council at Geneva discovered this fact a couple of years later and decided that they did not want to be involved in Calvin's missionary endeavors. The work throughout France continued to spread as Geneva continued to send preachers. Congregations were established around a similar structure as that in Geneva. Calvin's influence had reached a high in 1562. The Wars of Religion (1562-98) halted the spread of Calvinism. In 1598 it received toleration with the signing of the Edict of Nantes (1598). Elsewhere, it continued to spread.

W. Treatise On Predestination (1552)

1. Predestination and Providence

In 1552, Calvin's treatise on predestination was published. Like Zwingli, Calvin based his doctrine of predestination upon divine providence. Calvin’s conversion may not be dated precisely, but most Calvin scholars suggest it occurred in late 1533 or early 1534. On November 2, 1533, Nicolas Cop, the rector of the University of Paris, inaugurated the beginning of a new academic year by delivering an oration. Cop appears to have been assisted by Calvin in the drafting of this oration. Prior to this point in his life, Calvin was deeply devoted to the papacy and the Roman Church to such an extent that only an act of God could compel him to embrace another point of view. Though the precise cause of his turning from these deeply seated convictions may not be discerned, what is known is that from this point forward Calvin began to espouse Reformation theology, ostensibly having been influenced by Lutheran theology. This existential event was regarded as the providence of God that was ordering his life. In this way, providence was mingled with the doctrine of predestination in the thought of Calvin as it had been for Zwingli.

2. Single and Double Predestination

Often Calvinism is regarded as the remaking of Augustinianism . But so close an association of the thought of these two men may obscure the difference between them, and there are differences on the question of predestination.

Augustine, after his clash with Pelagius, never again viewed humanity with optimism. He regarded man as being completely impotent after the Fall, requiring the grace of God to provide salvation. At this point, there is no difference between Augustine and Calvin. The difference occurs at the point that grace is actualized. Augustine taught a single predestination in which God metered out grace to those whom He had chosen as partakers of eternal life. Those whom were not chosen were simply passed over, never enjoying any hope of salvation. Those who were the recipients of Divine grace were called the “elect”, and those who never enjoyed grace that led to salvation were the “nonelect ”.

Calvin disagreed with Augustine in that he believed that God did not merely forget about the nonelect, but rather God actively chose not to redeem the condemned. This view is known as double predestination. It is most likely that Calvin appropriated the schola Augustiniana moderna, exemplified by leading theologians such as Gregory of Rimini, which affirmed double predestination without regard to the merit or demerit of the individual, while stressing the absolute decrees of God. For the schola Augustiniana moderna and for Calvin, the eternal decrees of God concerned both the elect and nonelect, not of the elect only as was true fro Augustine. Calvin writes,

By predestination we mean the eternal decree of God, by which he determined with himself whatever he wished to happen with regard to every man. All are not created on equal terms, but some are preordained to eternal life, others to eternal damnation; and, accordingly, as each has been created for one or other of these ends, we say that he has been predestinated to life or to death.[18]

It should be noted that later Calvinism as reflected in Beza and the Synod of Dort does not accurately reflect Calvin’s interest in the subject of predestination. There is a difference between the thought of John Calvin and his theological descendants at this point. From 1570 onward, the themes of election and predestination came to dominate the theology of the Reformed Church. Under the influence of Peter Martyr Vermigli and Theodore Beza, these doctrines assumed a new level of social and political function.

X. English Refugees Sheltered (1555)

In 1555, Calvin began to give shelter to English Protestant refugees.

Y. Final Edition of the Institutes (1559)

In the 1559 edition, Calvin distributed his material in four books and the twenty-one chapters of the 1551 edition became eighty. Calvin’s Institutes were his greatest contribution to the Reformation. Lutheranism lacked a systematic treatment of its thought; as a result the Reformed tradition gained ascendancy.

Final form was given to the Latin edition of Calvin's Institutes (1559) and a year later a French translation was complete. In his 1539 edition of the Institutes, Calvin made use of the Latin and Greek Fathers. In addition, Calvin also referred to Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero.

Z. Beza and the Geneva Academy (1559)

In 1559, Calvin's academy in Geneva was founded upon the study of the "ancients" with Theodore de Beza (1519-1605) at its head; Beza had been a professor in Lausanne who had been expelled. About 1570, the doctrine of predestination gained a prominent place in Reformed theology. Calvinistic writers turned to Aristotle to provide their tradition with a firmer rational foundation.[19]

Calvin’s Death (May 27, 1564)

1564 On May 27, 1564, Calvin died at Geneva. Calvinism was formerly known as Augustinianism .

The Reformed Faith Outside Switzerland

I. Reformed Faith in France[20]

The Concordat of Bologna (1516) made allowance for the appointment of France's 10 archbishops, 38 bishops, and 527 heads of religious houses within the realm by the French monarch. As a result, the monarch was indifferent to the spiritual qualifications for church offices; he was more concerned with the revenues that could be raised from the patronage system. This fact explains why Francis I and Henry II zealously persecuted Protestants who opposed the patronage system.

A. Protestant Persecution Begins (1525)

Francis I, king of France, began to persecute Protestant sympathizers living in Meaux. The Reformation in France lacked leadership it enjoyed in other parts of the British Isles and Europe.

B. Gallican Confession Drafted (1559)

By 1559, there were nearly 400,000 Protestants living in France. The Protestant leaders at Geneva shared in the credit for the advancement of Protestantism in France. The first national synod was organized and held this year in Paris. The synod adopted a confession which was drawn up by Calvin, known as the Gallican Confession of Faith (1559).

C. French Protestants as “Huguenots” (1560)

After 1560, the French Protestants became known as Huguenots. They became so powerful that they nearly formed a kingdom within a kingdom.

D. Attacks against Huguenots (1538-1598)

From 1538 to 1562, French Protestants were fiercely persecuted, and from 1562 to 1598 they sustained eight fierce wars and massacres, the worst of which occurred on August 24, 1572. On this date, Gaspard de Coligny, early French Protestant leader, lost his life, along with fifteen to twenty thousand other Protestants, at the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572). The massacre was the impetus for the emergence of monarchomachism-the belief that the people of a nation possessed the right to resist tyrannical monarchs by severely restricting their rights or throwing off their rule completely. Calvin appears to have given rise to such beliefs in 1559 when he affirmed that a Christian was only compelled to be subject to a monarch who subjected himself to God. This position was advanced by French Huguenots and emerged again as the argument for the American Revolution.[21]

E. Religious Freedom for Huguenots (1598-1685)

For a little less than a hundred years, Protestants in France enjoyed religious freedom. But after this period of peace, the provision for peace was removed, and many believed it prudent to leave their native land and begin life anew where their faith would be tolerated.

1. The Edict of Nantes (1598)

King Henry IV, who had been a Protestant, issued the Edict of Nantes (1598) that granted religious freedom to the Huguenots. As a result, they formed a state within a state, enjoying a period of great prosperity while becoming a defensive minority.

2. The Edict of Nantes Revoked (1685)

In 1685, nearly 400,000 Huguenots were forced to flee France when the Edict of Nantes was revoked by Louis XIV. They made their way from France to England, Prussia, Holland, South Africa, and the Carolinas in North America.

The Reformed Faith in Scotland

F. Early Protestants Burned (1528, 1546)

1. Patrick Hamilton (1528)

Patrick Hamilton (ca. 1503-1528) was one of the first known Scottish Protestants. After having studied at Marburg and Wittenberg, he returned to Scotland where he proclaimed his Protestant theology. In 1528 he was arrested and burned at the stake for his denunciation of the doctrine and practice of the Catholic Church.

2. George Wishart (1546)

George Wishart (ca. 1513-1546) was also burned for his Protestant sympathies. Wishart, however, exerted considerable influence upon John Knox before his death.

G. Reform under John Knox

1. Knox Flees to Frankfurt (1553)

John Knox (1513-1572) fled to Frankfurt when Mary Tudor ascended the throne and rescinded the Protestant reforms that had been made under Edward.

2. Return to Scotland (1559)

In 1559, Knox returned to Scotland and penned his Treatise on Predestination (1559). The following year it was published in Geneva.

3. Scottish Parliament Takes up Reform (1560)

The Scottish Parliament met in 1560 to proceed with badly needed reform. Under this Parliament, the pope's control over the Scottish church was ended and the Scottish Confession of Faith accepted. The Scots Confession (1560) remained the sole standard of the Scottish Reformed Church until the Westminster Confession replaced it in 1647. The Reformation in Scotland was the work of “The Six Johns”: Willock, Spottiswoode, Douglas, Row, Winram, and Knox. Thus, the Scottish Reformation was accomplished bloodlessly.

4. Knox’s Death (1572)

John Knox died in 1572 with the middle class firmly in control of political development, and the Presbyterian system of church government and Calvinistic theology adopted by the Scottish people. Presbyterianism in America is a lineal descendant of the church established by Knox in Scotland.

The Reformed Faith in Ireland

H. Confiscation of Northern Ireland (1557)

In 1557, the English Parliament confiscated the land of Irish rebels in Northern Ireland and granted two-thirds of it to Scottish Presbyterians. Southern Ireland has remained loyal to the pope and has not experienced the strife so common to the north.

I. Dilution of Catholicism under James I (1611)

After James I ascended the throne in 1603, he decided to colonize Northern Ireland Scottish Presbyterians in 1611 in an effort to dilute the strength of Catholicism. But, in the early part of the eighteenth century, the English Parliament discriminated against Ireland economically.

J. Emigration to America (before 1710)

As a result of the economic discrimination that the English Parliament implemented against Ireland, many of the Presbyterians whose forefathers had immigrated to Northern Ireland from Scotland were forced to immigrate to America. By 1710, many Presbyterians had emigrated to New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

The Reformed Faith in Holland

K. The Rise of Modern Holland

1. Catholicism of Philip II (1555)

Philip II ascended the Spanish throne following his father's abdication in 1555. As a loyal Catholic, he was determined to bring the Spanish Netherlands back to the fold of the pope.

2. Protestants Protest Inquisition (1565)

The Noblemen of the Netherlands formed the Compromise of Breda in 1565 and petitioned King Philip to suspend the Inquisition and the laws against heretics.

3. Flanders and Holland Uprisings (1565-66)

Uprisings occurred in Flanders (1565) and in Holland (1566) and was orchestrated by Protestants. King Philip responded by appointing the Duke of Alva as the regent of the Netherlands in 1569. Between 1567 and 1573 Alva had executed nearly two thousand people, and by the end of the century, forty thousand had migrated to other countries.

4. William of Orange Revolts (1568)

William of Orange, known as the Silent, raised the standard of revolt against Spain in 1568. But William was no match for Alva's soldiers, and was forced to retire to Germany.

5. Dutch War at Sea (1569)

Because war against Alva and his Spanish troops on land appeared hopeless, the Dutch took to the sea in 1569 in an attempt to prey on Spanish commerce.

6. Spanish Driven Out (1576)

The city of Antwerp was captured, looted, and the Spanish soldiers under Alva's successor killed seven thousand. This act so infuriated Holland, Zeeland, and other provinces that they united in the Pacification of Ghent in 1576 to drive out the Spanish.

7. Dutch Union Formed (1579)

Seven northern Dutch provinces signed the Union of Utrecht in 1579, and in 1581, the sovereignty of the Spanish King was formally refuted.

William of Orange was assassinated in 1584. He is responsible for having laid the foundation for the modern state of Holland. Eventually the Dutch won their freedom from Spanish domination.

8. English Defeat Spanish Armada (1588)

In 1588, the English defeated the Spanish Armada, ensuring ensured that the Dutch would be relatively free from Spanish efforts to recapture them.

9. Independence Ensured by Westphalia (1648)

The end of the war with Spain was not formally recognized until the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. In 1689, Holland gave England a King.

L. Calvinism in Holland

1. Protestants Burned at Brussels (1523)

The first Protestant martyrs were burned at the stake in Brussels. Also, the first Dutch New Testament was published in 1523. This enabled the Dutch to compare the New Testament church with the Church of Rome.

2. Anabaptism Grows in Holland (1525-1540)

Prior to 1525, those who accepted Protestant thought followed Luther. This trend changed following this date. Between 1525 and 1540, the Anabaptists attracted a strong following in Holland.

3. Calvinism Gains Ascendancy (1540ff)

From 1540, Calvinism held sway over the Reformation in Holland. The majority of Protestants were Calvinists by 1560. Small minorities, however, remained committed to Lutheran and Anabaptist thought and practice.

4. Theological Standards (1562, 1566)

The Belgic Confession (1566) was adopted by a synod at Antwerp for use in the Reformed church in Holland. In 1574, the Confession received approval from the national synod at Dort . The Belgic Confession along with the Heidelberg Catechism (1562) became the theological standards of the Reformed churches in Holland.

5. Presbyterian Government Accepted (1571)

The Presbyterian system of church government was accepted at a national synod in Emden in 1571.

[1] The reformer of St. Gall. His birth name was Joachim von Watt, but he changed his name when studying at Vienna, as was the pedantic custom of that era.

[2] He was better known as Henricus Glareanus, whose original name was Heinrich Loris. Glareanus was a Swiss Humanist, poet, and music theorist, most widely known for his publication Dodecachordon (Basel, 1547). After coming under the influence of Erasmus, he championed the new Humanism. Though initially affected by the Reformation, he subsequently rejected it and vigorously opposed it the Swiss Reformers, including his one-time friends Huldreich Zwingli and John Oecolampadius.

[3] Faber’s, whose name was Felix Fabri, was a Dominican monk.

[4] His full name was Johann Maier von Eck . In 1510, he was appointed professor of theology at the University of Ingolstadt, over which he ruled the rest of his life.

[5] Relating to, having the nature of, or constituting a title with very little, if any, responsibilities related to the office.

[6] On April 29, 1521, Zwingli was promoted to Canon.

[7] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 171.

[8] Hoen's understanding of the Eucharist has been influenced by Wessel Gansfort (ca. 1420-89) and his work, On the Sacrament of the Eucharist. McGrath, Reformation Thought, 173.

[9] The pagan fatalism of Seneca gave rise to the fatalism of the Reformed and Calvinistic tradition. See Seneca’s influence on Calvin below (page 16).

[10] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 120-23.

[11] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 109-110.

[12] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 110-11.

[13] It is evident that Zwingli was influenced by Seneca's pagan fatalism. Both Zwingli and Calvin appear to have been greatly influenced by Seneca concerning predestination. McGrath, Reformation Thought, 121.

[14] It is not certain that Calvin helped Cop write the address.

[15] It may be noted that the Consistory did not execute Michael Servetus. The execution was carried out by the city council.

[16] This Protestant confession of faith was composed in 1562 by Z. Ursinus and K. Olevian, two Heidelberg theologians, and others at the insistence of the Elector Frederick III. It became the standard of doctrine in the Palatinate after it was accepted in 1563.

[17] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 111.

[18] Taken from Henry Beveridge ’s translation of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1599), III.xxi.5. See Appendix A below.

Calvin embraced Augustine's concept of divine sovereignty. Augustine, in his early theological career, denied the doctrine of divine sovereignty. Augustine's theological transition began with his debates with a British monk by the name of Pelagius. Pelagius was in Rome in 410 when the Goths attacked the city. Along with his supporter Celestius, Pelagius fled Italy for Africa. Soon he moved on to Palestine. In his wake he left a humanistic understanding of salvation. Augustine of Hippo soon encountered Pelagius' teachings and responded by insisting that all salvation was a result of divine decree (ca. 411).

In 529, at the Council of Orange, the Church refuted Augustine's double predestination and irresistible grace was omitted from the creed. The Church did not hold to the doctrines of Augustine before 411, nor did it hold to it after Augustine. It was not until the sixteenth century that the doctrines of Augustine were revived in the thought of Calvin.

[19] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 125, 129.

[20] See J. E. Neale, The Age of Catherine de Medici (New York: Harper and Row, 1962) for more detailed explanation of the Protestant movement in France.

[21] McGrath, Reformation Thought, 228-30.