The degree to which Christianity influenced the birth and development of the nation is seldom understood by contemporary Americans. According to many current historians, Founding Fathers rejected the influence and observance of Christianity in American political life. But, nothing could be further from the truth. While eight of America's first thirteen states had established state churches, all of the states from the colonial charters to their first constitutions contained affirmations of the Christian faith. The evolving federal government—including the Constitution—never intended to dictate to states whether they could retain their own state churches; for this reason, the Constitution ensured that the federal government would not establish a federal state church—something that was universally recognized in legal decisions until the middle of the twentieth century when liberal influences began to erode the American court.Congress Begins Thanksgiving Cycle

One of the many ways of demonstrating that America's Founding Fathers never intended to refuse Christianity an influential role in American political life is the careful observance of Congress' own practice. From the First Continental Congress in 1774, Congress immediately took measures to accord Christianity a role in America's governmental formation. The following year, in the Second Continental Congress, representatives began specific Christian spiritual practices that were generally observed twice a year until the cessation of the War of Independence in 1784. In all, sixteen spiritual proclamations were issued by Congress between 1775 and 1784. The proclamation of November 1, 1777—which is discussed below—is unique in that it began the second half of the annual spiritual cycle of Congress, which was the "thanksgiving" proclamation. With these proclamations, Congress urged all states to ask their citizens to fast, pray, and give thanks to God.

The subject addressed in this article is discussed at greater length in When Congress Asked America to Fast, Pray, and Give Thanks to God. Christian Heritage Fellowship would be honored to work with individuals, businesses, churches, institutions, or organizations to help communicate the truth concerning the positive influence of the Christian faith by providing bulk pricing: Please contact us here... To purchase a limited quantity of this publication, please click: Purchase here...

Article Contents

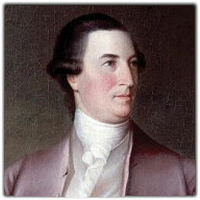

Henry Laurens President of Congress

Following the December 11, 1776 "day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer" proclamation, nearly a year passed before Congress issued another spiritual proclamation. This time, it was passed under the new President of Congress, Henry Laurens, who served in this capacity for thirteen months, from November 1, 1777 to December 9, 1778. Henry Laurens was a merchant, planter, and revolutionary statesman from South Carolina who was a descendant of Protestant French Huguenots. Elected to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly in 1757, he maintained a political career from that time until the Revolution.[1] Two weeks after assuming the presidency of Congress, he signed the Articles of Confederation (November 15, 1777) which acted as America's first constitution between the states. Following the Declaration of Independence, it was the second of America's four "organic laws" that cannot be set aside by other laws.

Throughout 1777, Continental and British forces engaged each other in battles, skirmishes, and tactical maneuvers on more than a dozen and a half occasions. Returning to Philadelphia on March 5, 1777 after fleeing the city in December, Congress was once again forced to flee Philadelphia in September 1777 due to the American loss at the Battle of Brandywine (September 11). Finally settling at the York Court House in south-central Pennsylvania, Congress resided there from September 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778. Having outmaneuvered Washington after the Battle of Brandywine, the British were able to march into Philadelphia unopposed on September 26, 1777, occupying the city until June 1778—which was the British "Philadelphia Campaign," designed to conqueror the American's capitol.[2] While Congress resided at the York Court House, representatives both drafted and adopted the Articles of Confederation, though they were not fully ratified by the States until March, 1781.

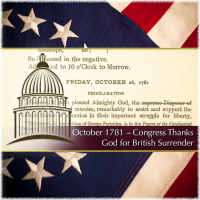

While Congress was in "exile" at York, it also issued its fourth spiritual proclamation, this time for a very different reason than fasting and praying. As the Revolutionary War entered its second year, the British decided to drive their forces between the New England States on one hand and the Middle and Southern States on the other. One of the British forces designated to execute the plan was commanded by General John Burgoyne, who led his forces out of Quebec to gain control of the upper Hudson River valley of New York. One British force marching from New York City and another force marching eastward from Lake Ontario were to rendezvous with General Burgoyne, thereby dividing the states. However, the British forces from New York and Lake Ontario failed and General Burgoyne found himself surrounded by American forces. After two battles waged eighteen days apart on September 19 and October 7, 1777, Burgoyne retreated to Saratoga, but seeing no relief from other British forces, surrendered his entire army on October 17. Had the British plan to divide the states succeeded, it is likely the American cause would have been lost. The surrender of General Burgoyne has been memorialized in one of the large paintings hanging in the United States Capitol Rotunda. This event marked a turning point in the Revolution allowing American forces to advance their cause. Realizing the importance of Burgoyne's surrender, Congress was prepared to ask the fledgling nation to express its gratitude to God for its great victory.

In the New England Colonies, a cycle of fasting in the spring and giving thanks to God in the fall had existed since the seventeenth century. And, beginning with November 1777, Congress began to use that full cycle of fasting in the spring and giving thanks in the fall, exercising its influence over the states—something that was continued until the end of the Revolution.[3] In fact, the last spiritual proclamation issued by Congress was issued in August 1784 and was a thanksgiving proclamation issued in gratitude for the cessation of the War.

Congressional Committee Composes Proclamation

As was the case for most spiritual proclamations issued by Congress, it was composed, not by one person, but by a designated committee. What was unique about this committee is the fact that it was the first committee to be charged with returning a "recommendation . . . for a day of thanksgiving."

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1777

Resolved, That a committee of three be appointed to prepare a recommendation to the several states, to set apart a day of thanksgiving, for the signal success, lately obtained over the enemies of these United States: The members chosen, Mr. S[amuel] Adams, Mr. R[ichard] H[enry] Lee, and Mr. [Daniel] Roberdeau.[4]

The day after the committee was selected and charged to write Congress' first thanksgiving proclamation, Congress as a whole received the committee's draft and approved the following:

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1777

The committee appointed to prepare a recommendation to these states, to set apart a day of thanksgiving, brought in a report; which was agreed to as follows:

Forasmuch as it is the indispensable duty of all men to adore the superintending providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with gratitude their obligation to him for benefits received, and to implore such farther blessings as they stand in need of; and it having pleased him in his abundant mercy not only to continue to us the innumerable bounties of his common providence, but also to smile upon us in the prosecution of a just and necessary war, for the defense and establishment of our unalienable rights and liberties; particularly in that he hath been pleased in so great a measure to prosper the means used for the support of our troops and to crown our arms with most signal success: It is therefore recommended to the legislative or executive powers of these United States, to set apart Thursday, the eighteenth day of December next, for solemn thanksgiving and praise; that with one heart and one voice the good people may express the grateful feelings of their hearts, and consecrate themselves to the service of their divine benefactor; and that together with their sincere acknowledgments and offerings, they may join the penitent confession of their manifold sins, whereby they had forfeited every favor, and their humble and earnest supplication that it may please God, through the merits of Jesus Christ, mercifully to forgive and blot them out of remembrance; that it may please him graciously to afford his blessing on the governments of these states respectively, and prosper the public council of the whole; to inspire our commanders both by land and sea, and all under them, with that wisdom and fortitude which may render them fit instruments, under the providence of Almighty God, to secure for these United States the greatest of all human blessings, independence and peace; that it may please him to prosper the trade and manufactures of the people and the labour of the husbandman, that our land may yet yield its increase; to take schools and seminaries of education, so necessary for cultivating the principles of true liberty, virtue and piety, under his nurturing hand, and to prosper the means of religion for the promotion and enlargement of that kingdom which consisteth "in righteousness, peace and joy in the Holy Ghost."

[Note 1: 1 The original read: "That at one time and with one voice."]

And it is further recommended, that servile labour, and such recreation as, though at other times innocent, may be unbecoming the purpose of this appointment, be omitted on so solemn an occasion.[5]

While some may wish to quibble about points of doctrine contained in this proclamation, the fact that there are sixteen similar proclamations diminishes the success of their argument. When considering this proclamation within the context of every other similar proclamation, it becomes abundantly evident that the Founding Fathers were not deists but overwhelmingly Christian in their theology. And, what is more, anti-Christian writers cannot demonstrate how some personally held unorthodox theological opinions of Founding Fathers ever impacted state or federal governments. Those who argue otherwise should consider Pennsylvania's first state constitution which required that state office holders should affirm the Divine inspiration of both the Old and New Testaments; Benjamin Franklin's name is at the bottom of the document, for he was the chairman of the convention. And, do not forget Thomas Jefferson was one of the founding members of the Virginia Bible Society—to name only a couple of the orthodox positions of two Founding Fathers who were less orthodox in their Christian theology. They were, however, more orthodox than many contemporary professing Christians! Congress' spiritual proclamation of November 1, 1777 is only one of thousands of pieces of evidence that demonstrate America was founded upon Christianity.

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

[1] Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "Laurens, Henry," https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofamer11amer.

[2] European warfare was often directed against the capitol of opposing forces. Once the capitol was conquered it was believed the war was at an end. "Philadelphia Campaign," Wikipedia, October 9, 2017; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philadelphia_campaign.

[3] Davis, Religion and the Continental Congress, 83-84.

[4] Journals of the Continental Congress, 9:851.

[5] Journals of the Continental Congress, 9:854-855.