Thomas Paine is often employed by the political left as justification for their false claim that America was established as a secular nation. The facts, however, completely expose their uninformed argument. Click to read the entire article…

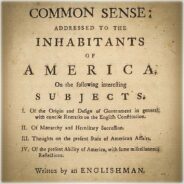

While Thomas Paine is remembered positively for his contribution to American independence through his book, Common Sense, his contemporary defenders overstate his influence when they credit him as being the primary force of the American cause. His supporters associate Paine's later deistic beliefs of the 1790s with the widespread acclaim he enjoyed after Paine's 1776 publication of Common Sense. The fact is that American Founding Fathers rejected Paine for his deism after he turned from the biblical principles that Paine espoused in Common Sense.

Present-day secularists who seek to use Paine as a battering-ram against the presence of Christianity in public life attempt to employ that portion of his life that contributed positively to the American cause of independence while neglecting the latter portion of his life—which completely undermined his previous contribution. While Paine's literary contribution in Common Sense (published in 1776) may be applauded, his Age of Reason (published in the 1790s) was regarded as an attack upon the political life of any Christian nation. For this reason, Thomas Paine went to his grave, not in the stately grandeur of a heroic friend, but in the disgrace and abandonment of a foe.

The lines that follow briefly chronicle the related facts.

Article Contents

Early Education and Employment

Thomas Paine was born on January 29, 1736 in Thetford England to Joseph Pain (also written Paine), a Quaker, and Frances (n. . . e Cocke), an Anglican. Thomas attended Thetford Grammar School for only a few years from 1744 to 1749, and at the age of thirteen was apprenticed to his father who was a stay-maker. While it has been popularly circulated that Paine's father made stays for ladies corsets, Thomas Paine's advocates have argued he made stay ropes for the shipping industry. This observation is possible given the fact that the town of Thetford where they lived at that time enjoyed brisk business with the downriver port town of King's Lynn.[1]

Thomas enlisted for a brief period in the shipping industry, traveling abroad but returning to Britain in 1759. That same year he became a master stay-maker, establishing a shop in Sandwich, Kent, and on September 27, 1759, Thomas married Mary Lambert, but soon after, his business collapsed. Mary became pregnant and after they moved to the town of Margate, she went into early labor in which both she and her child died.

Returning to Thetford, the town of his birth, he received temporary employment as a watchman. Moving to Grantham, Lincolnshire, he became an excise officer in December 1762. In August 1764, he was transferred to Alford, Lincolnshire, but a year later, on August 27, 1765, he was dismissed as an excise officer for failing to inspect goods he claimed to inspect. After nearly a year of work as a stay-maker, his request for reinstatement as an excise officer was granted on July 31, 1766.[2]

From 1767 to 1774, Paine lived an unsettled life—which was characteristic of his entire adult life. In 1767, he was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall, which was followed by a short stint as a schoolteacher in London. In 1768, he was appointed to a position in Lewes, Sussex where he met and married Elizabeth Ollive, his landlord's daughter. It was in Lewes that Paine first became engaged with civic matters, serving on the church parish vestry for a period of time. In 1772, he published his first political writing titled, The Case of the Officers of Excise. On June 4, 1774—after little more than three years of marriage—he separated from Elizabeth and moved to London where in September he was introduced to Benjamin Franklin, who suggested that he emigrate to the American colonies. With a letter of recommendation from Franklin, Paine seized the opportunity and sailed for America the following month, arriving in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774.

Though noted for some inventions, history has remembered Thomas Paine as a literary figure. After recovering from an illness contracted aboard the ship to America, Paine assumed the editorship of the Pennsylvania Magazine in January 1775. A year later, on January 10, 1776, he anonymously published his Common Sense, advocating American independence from Great Britain and soon after began a series of articles known as The American Crisis (1776-1783).

In addition to enjoying the friendship of Benjamin Franklin, Paine also enjoyed the acquaintance and friendship of another of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and leading citizen of Philadelphia, Dr. Benjamin Rush. Along with George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Rush was regarded among the three most important men of America's Founding Fathers.[3] Those who attack the Christian origin of America are often uninformed concerning the most important influences related to the founding of America. While secularist extol Thomas Paine's authorship of Common Sense, they do so not because of its theistic or Christian content, but because of the religious opinions that Paine assumed upon traveling to France after the publication of Common Sense. The influence of the deeply committed Christian evangelical, Dr. Benjamin Rush, upon Paine's writing of Common Sense was profound, as noted by one biographer:

It was he [Dr. Benjamin Rush] who encouraged Thomas Paine to write Common Sense, for which Rush not only supplied the title but many of its ideas.[4]

Thomas Paine's Common Sense was not at all like his writings at the end of his life. In Common Sense, Paine uses arguments from Scripture, and in this way credits Scripture with authority in matters of human government. Also, it is evident that Paine believed in the "providence" of God in the affairs and government of mankind. He did not believe that God had not made the world and walked away as the deists believed—as secularists naively assert concerning Paine and other Founding Fathers; rather, his argument against government by monarchy is based upon the Bible and its authority. One brief quote from Common Sense will demonstrate this fact:

The children of Israel being oppressed by the Midianites, Gideon marched against them with a small army, and victory, thro' the divine interposition [providence], decided in his favor. The Jews elate with success, and attributing it to the generalship of Gideon, proposed making him a king, saying, Rule thou over us, thou and thy son and thy son's son. Here was temptation in its fullest extent; not a kingdom only, but an hereditary one, but Gideon in the piety of his soul replied, I will not rule over you, neither shall my son rule over you. The Lord shall rule over you. Words need not be more explicit; Gideon doth not decline the honor, but denieth their right to give it; neither doth he compliment them with invented declarations of his thanks, but in the positive stile of a prophet charges them with disaffection to their proper Sovereign, the King of heaven.[5]

Those who deny the Christian origin of America do so against the historical facts, including the literary legacy of one of their patron saints—Thomas Paine. At this point in his life, Paine believed what other Founding Fathers believed, that there was only one "proper Sovereign" who was "the King of heaven," and was by extrapolation, the Sovereign of earth as well.

However, Paine's biblical political views changed in the ensuing years of life. Upon immigrating to America, Paine was well received by some of America's most distinguished Founding Fathers, including the most deeply committed Christians, and the publication of Common Sense did not diminish those relationships. But the instability of Thomas Paine's character that had already revealed itself in his English homeland shadowed him the remainder of his life, including his initial settling in America. The years that followed only exacerbated character flaws already present in Paine, resulting in a rift with American Founding Fathers who had initially befriended him.

Characteristic of much of his life, Paine soon found himself at odds with leading figures of the American Revolution. Following the War of Independence, he returned to England for only a few years before making his way to France in 1790. Unlike the American Revolution, the French Revolution of 1789 and the many years that followed were the result of the godless influence of Voltaire, Rousseau, and the European "Intellectuals." From these wells of irreligion that sprang from the French Revolution, Paine drank freely and deeply—a fact that was reflected in his subsequent writings.

Though Paine produced other works, two writings defended the irreligious French Revolution and the philosophy that justified its horrors. The first of these two works, Rights of Man (1791), included thirty-one articles that argued in defense of revolution when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people.[6] The second work, The Age of Reason—published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807, was a traditional deistic attack upon Christianity, institutional religion, and denied the legitimacy of the Bible. Particularly the latter work amounted to a betrayal of the Founding Father's understanding of the foundation of human government.

By 1803, Paine had returned to America with the encouragement of Thomas Jefferson. By this time, the first two parts of his Age of Reason had been published and received with deep distain in America. In fact, America's Founding Fathers had little to do with Paine upon his return, and evoked open and strong rebuke for his infidelity and attack upon Christianity. One of the first to warn him against publishing Age of Reason was one of the Founding Fathers that secularists presently attempt to exploit to their cause—Benjamin Franklin. Paine had sent a manuscript copy of this work to Mr. Franklin prior to its publication, apparently seeking Franklin's approval for his plan, but after reading it, Franklin responded in a letter, urging him not to publish it. As he closed his letter to Paine, Franklin expostulated,

…think how great a portion of mankind consists of weak and ignorant men and women, and of inexperienced, inconsiderate youth of both sexes, who have need of the motives of religion to restrain them from vice, to support their virtue, and retain them in the practice of it till it becomes habitual, which is the great point for its security. And perhaps you are indebted to her originally, that is, to your religious education, for the habits of virtue upon which you now justly value yourself. You might easily display your excellent talents of reasoning upon a less hazardous subject, and thereby obtain a rank with our most distinguished authors. For among us it is not necessary, as among the Hottentots [or heathen], that a youth, to be raised into the company of men, should prove his manhood by beating his mother.

I would advise you, therefore, not to attempt unchaining the tiger [or publish this work], but to burn this piece before it is seen by any other person; whereby you will save yourself a great deal of mortification by the enemies it may raise against you, and perhaps a good deal of regret and repentance. If men are so wicked with religion, what would they be if without it. I intend this letter itself as a proof of my friendship, and therefore add no professions to it; but subscribe simply yours,

B. Franklin[7]

Though influenced in his late teens by deism and infidelity, Benjamin Franklin came to realize that disregard for God was only the preface to disregard for man; he realized it only produced heartache and misery. Throughout world history, irreligion in the forms of agnosticism, atheism, and deism has never produced a highly civilized society—but only repression and anarchy.

Another noted Founding Father who strenuously resisted Paine's irreligion was Elias Boudinot, one-time president of the Continental Congress and founding president of the American Bible Society. With other Founding Fathers, Boudinot was incensed by Paine's Age of Reason and openly challenged Paine by publishing his own response in 1801 titled, The Age of Revelation, or The Age Of Reason Shown to Be an Age of Infidelity. In his book, Boudinot not only demonstrated his contempt for Paine's irreligion but also disclosed the contempt that America's Founding Fathers had for secular infidelity and deism. In his introduction to his refutation of Paine, Boudinot wrote:

When I first took up this treatise [Paine's Age of Reason], I considered it as one of those vicious and absurd publications, filled with ignorant declamation and ridiculous representations of simple facts, the reading of which, with attention, would be an undue waste of time; but afterwards, finding it often the subject of conversation, in all ranks of society, and knowing the author to be generally plausible in his language, and very artful in turning the clearest truths into ridicule, I determined to read it, with an honest design of impartially examining into its real merits.

I confess, that I was much mortified to find, the whole force of this vain man's genius and art, pointed at the youth of America, and her unlearned citizens, (for I have no doubt, but that it was originally intended for them) in hopes of raising a skeptical temper and disposition in their minds, well knowing that this was the best inlet to infidelity, and the most effectual way of serving its cause, thereby sapping the foundation of our holy religion [Christianity] in their minds.

. . . be assured . . . [reader] that this author's whole work, is made up of old objections, [that have already been] answered, and that conclusively, [answered] a thousand times over, by the advocates for our holy religion. Some of them he has endeavored to clothe with new language, and put into a more ridiculous form; but many of them he has collected almost word for word, from the writings of the deists of the last and present century.[8]

While some present-day secularists would have America believe that Thomas Paine pillowed his head in his grave with comparable esteem accorded other Founding Fathers, nothing could be further from the truth. When Paine divorced himself from the biblical principles he espoused in Common Sense and later embraced the infidelity of the French Revolution, America rejected one of the champions of her independence. Nothing is more glaring in support of this than the fact that, following his death on June 8, 1809 at Greenwich Village, New York City, only six individuals attended his funeral. When the Quakers at New Rochelle would not allow him to be buried in their cemetery, he was laid to rest under a walnut tree on his own farm.[9]

Evaluation: Paine and the Founding Fathers

Late in life, Thomas Paine greatly deviated from the Christian principles that established American government. While it is true that two leading figures of the American Revolution—Benjamin Frank and Thomas Jefferson—did deny the deity of Jesus Christ,[10] they did not believe that religion in general, nor more importantly Christianity, should be excluded from a public influence of government. To provide evidence of this fact, when the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention was convened after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Franklin was elected chairman of the Convention, and on September 28, 1776, he signed Pennsylvania's first constitution that stipulated a Christian test to hold public office in state government. Section ten of Pennsylvania's first constitution read as follows:

And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, … [namely] : 'I do believe in one God, the Creator and Governor of the Universe, the Rewarder of the good and the Punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine Inspiration.'[11]

Only those affirming the "Divine Inspiration" of the New Testament (and the doctrines it advocated) could hold office in the Pennsylvania legislature—and Pennsylvania was joined by all the other states in similar affirmations in their respective state constitutions. Unlike the deism that Thomas Paine later embraced, the overwhelming majority of America's Founding Fathers believed—like the constitution of Pennsylvania—"in one God" who was both "Creator and Governor of the Universe." Since deism teaches that God walked away from what he made, it did not believe God continued to govern the world, nor did it believe that the "Old and New Testament to be given by Divine Inspiration," because deism denied that God related to the world in any way. Further, Pennsylvania's first constitution affirmed that God was taking account of world affairs and would bring to account every individual in a future state as "the Rewarder of the good and the Punisher of the wicked." Clearly Pennsylvania and the other states were not ashamed to integrate Christian doctrine into their constitutions.

Conclusion: Paine and Irreligious Betray America

But secularists, atheists, agnostics, deists, and the irreligious cannot look to Thomas Jefferson in defense of Thomas Paine either. Just as Benjamin Franklin is falsely touted as a deist and advocate of secular government, so ill-informed secularists also seek to co-opt Thomas Jefferson into their scheme to blaspheme America's Christian heritage by attempting to ascribe America's origin to irreligious beginnings. Thomas Jefferson, however, will have nothing to do with such uninformed opinions. In one of his first books, Jefferson clearly identified his understanding of the place religion or Christianity must be accorded in human government—that the liberties of America were a "gift from God," not a right granted by any human court:

And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever.[12]

President John Adams also clearly identified the fact that the War of Independence was waged under the influence of Christian principles. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson dated June 28, 1813, Adams wrote:

The general principles, on which the [Founding] Fathers achieved independence, were . . . the general principles of Christianity, in which all those sects [or Christian denominations] were united; and the general principles of English and American liberty, in which all those young men united, and which had united all parties in America, in majorities sufficient to assert and maintain her Independence.[13]

How then did Thomas Paine and how do secularists betray America? By denying the Christian principle that the right of human government is both given and sustained by God—something that was argued in the first two paragraphs of America's first organic law, the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776):

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men…[14]

America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

"Anchor Elements" are concepts, events, individuals, terms, or other important components that are featured in this article and which act as reference points for use in other articles throughout our site.

[1] "Thomas Paine," Wikipedia, accessed January 27, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Paine.

[2] "Thomas Paine."

[3] John Sanderson, Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: R. W. Pomeroy, 1823), 4:285.

[4] Alyn Brodsky, Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician, 1st ed. (New York: Truman Talley Books, 2004), 5.

[6] "Rights of Man," Wikipedia, accessed January 27, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rights_of_Man.

[8] Elias Boudinot, The Age of Revelation, or, the Age of Reason Shewn to Be an Age of Infidelity (Philadelphia: Asbury Dickins, 1801), xii, xiv, xv.

[9] "Thomas Paine."

[10] Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson denied that Jesus Christ was God, as taught in Scripture and by orthodox Christians.

[11] "American Minute with Bill Federer," April 17, 2015.

[12] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, A New Edition ed. (Richmond, VA: J. W. Randolph, 1853), 174-175.

[13] Original orthography updated. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 6, Retirement Series, 11 March to 27 November 1813 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 236-39.

[14] "Declaration of Independence: A Transcription," National Archives: America's Founding Documents, accessed December 30, 2016. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.