- 3

- 4shares

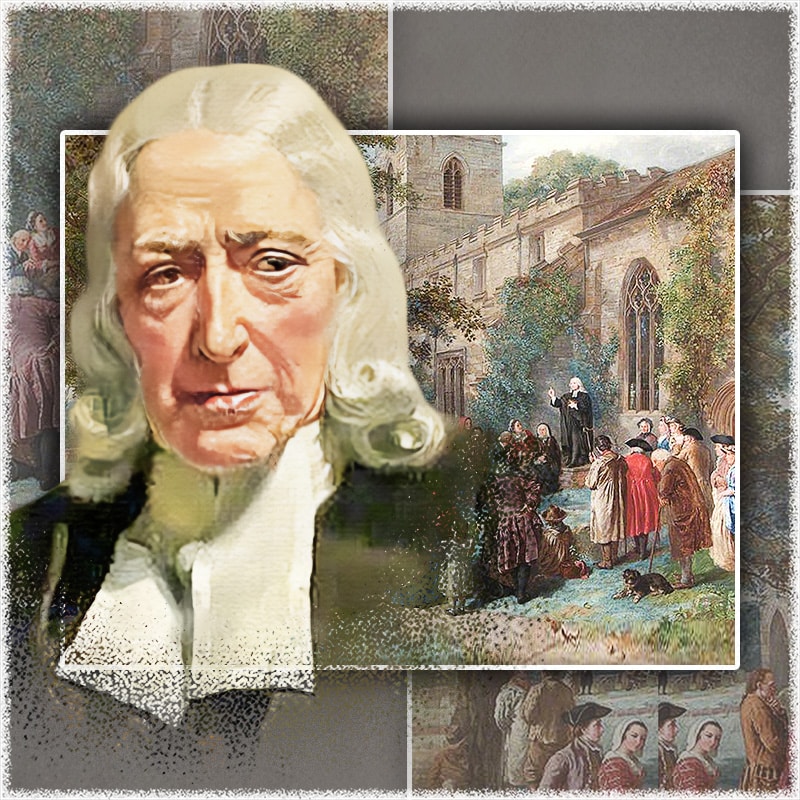

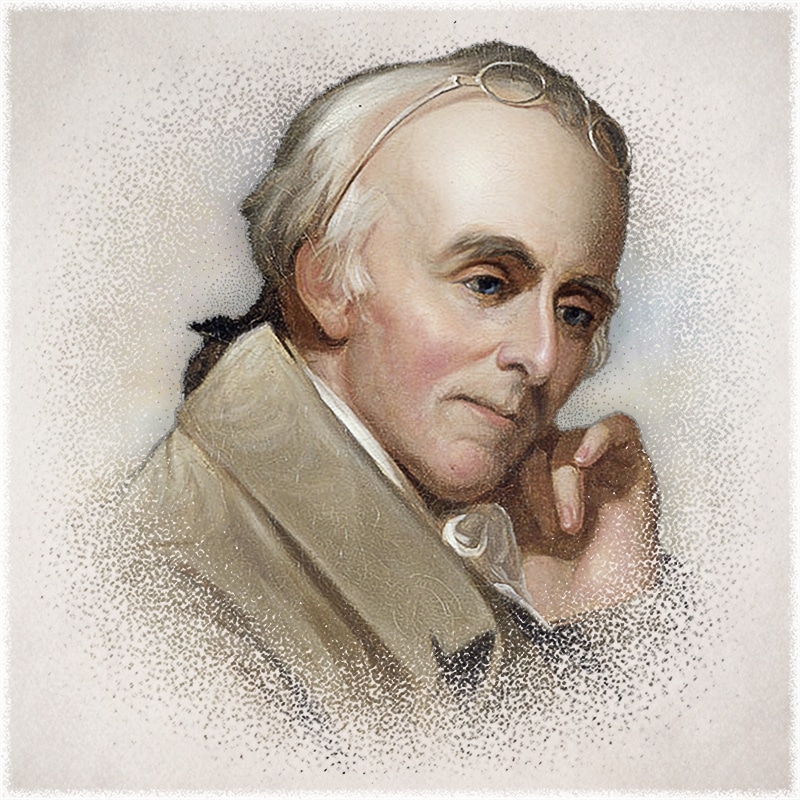

John William Fletcher is often referred to as the “First Theologian of Methodism.” He earned this popular title as a result of having vigorously defended John Wesley’s Arminianism against Calvinistic polemical rivals. In the early- and mid-1770s, Fletcher undertook the defense of Wesley against Calvinists who charged Wesley with Pelagianism or works righteousness. Fletcher insisted that Wesley affirmed the aphorism, “All salvation is of God in Christ through faith; all damnation is of self,” not the result of God or Satan. The following pages are an attempt to roughly sketch his life.

I. Birth at Nyon, Switzerland (September 12, 1729)

John William Fletcher was born in a French-speaking canton in Nyon, Switzerland on September 12, 1729.

II. Education at Geneva College (ca. 1740-41?)

At the age of eleven or twelve, Fletcher was sent to live in Geneva and was enrolled in the Geneva College, a bastion of Calvinism.

III. Matriculation to Geneva University (1746-48)

In 1746, at the age of seventeen, Fletcher enrolled at the University of Geneva and graduated two years later (1748) with a degree in philology—a degree which prepared students for studies in law or theology. However, he left the university before entering into theological studies, choosing rather to enter into a military career.

Early Years in England (1750-1760)

I. Learns English (1750-1751)

Having become discouraged over his inability to secure a military career, Fletcher left Switzerland for a trip to England. Upon entering England in the summer of 1750, Fletcher spent more than a year learning the English language.

II. Begins Life as a Tutor (1751)

After becoming more acquainted with the English language, Fletcher was employed as a tutor, in the autumn of 1751, to the two sons of Thomas Hill, a member of the English Parliament. Fletcher remained with the Hill family until 1760. From late 1751 to 1760, Fletcher—along with the Hill family—traveled to London where they remained, generally, from November to May. In April or May Fletcher would accompany the family to their summer home outside of Shrewsbury, Shropshire.

III. Contact with Methodists (1753, Autumn)

In the autumn of 1753, Fletcher sought out the Methodists at West Street and Hog Lane in London after a contact with a godly woman who was believed by the Hill family to be a Methodist.

IV. Conversion under Methodists (January 24, 1754)

Soon after coming into contact with the Methodists of London, Fletcher came under conviction for his sin, and after intense struggle was converted on January 24, 1754.

Entrance into the Priesthood (1757)

I. Initial Inquiry (November 24, 1756)

While a tutor for the Hill family, Fletcher began to sense a call into the priesthood of the Anglican Church. In a letter to John Wesley, Fletcher invited Wesley to pass judgment on Fletcher regarding his qualifications for the ministry. Though no written response to Fletcher’s inquiry is extant, it is believed that Wesley encouraged Fletcher to pursue the priesthood.

II. Ordination as Deacon (March 6, 1757)

Fletcher was ordained deacon at the chapel in Spring Gardens, Westminster (London).

III. Ordination as Priest (March 13, 1757)

One week after he was ordained a deacon, Fletcher was ordained a priest at the royal chapel of St. James, Westminster (London).

IV. Appointed to Madeley Curacy (March 14, 1757)

The day after his appointment to the priesthood, Fletcher was appointed to the curacy of Madeley parish, Shropshire and declared his commitment to the liturgy of the Anglican Church. However, he remained in the home of the Hill family and the tutor of the two Hill boys. Not until after the two boys left home for the university did Fletcher leave the Hills to assume his responsibilities full-time in Madeley parish (1760).

V. “Heads of Examination for Adult Believers” (September 1758)

Early in his relationship to Methodism, Fletcher was invited to participate in the discussions which led to early Methodism’s most definitive statements concerning Christian perfection. On August 10, 1758, Wesley’s fifteenth Conference was convened in Bristol. One of the main points of discussion was the doctrine of Christian perfection was again considered.[1] In summary, the Conference concluded . . .

1. That Christian Perfection does not “exclude all infirmities, ignorance, and mistake.”

2. That those who think they have attained Christian Perfection, in speaking their own experience, should “speak with great wariness, and with the deepest humility and self-abasement before God.”

3. That young preachers, especially, should “speak of Perfection in public, not too minutely or circumstantially, but rather in general and scriptural terms.”

4. That Christian Perfection “implies the loving God with all the heart, so that every evil temper is destroyed, and every thought, and word, and work springs from, and is conducted to the end by, the pure love of God and our neighbour.”[2]

A month after his Bristol Conference, Wesley convened an informal meeting with some of his preacher, of which Fletcher was a part, to again discuss the subject of Christian perfection. In his journal entry for September 9, Wesley writes,

I wrote the account of an extraordinary monument of divine mercy, Nathaniel Othen,[3] who was shot for desertion at Dover Castle, in October, 1757. In the following week, I met Mr. Fletcher, and the other preachers that were in the house, and spent a considerable time in close conversation on the head of Christian perfection. I afterwards wrote down the general propositions wherein we all agreed.”[4]

The result of this meeting, until recently, has been relatively unknown. This informal meeting focused its attention primarily upon standards whereby the claims of perfect love may be established objectively. One short work resulting from this meeting between Wesley and his preachers has been found in Fletcher’s collective Works since the early nineteenth century: “The Test of a New Creature, or, Heads of Examination for Adult Christians.”[5] The original, varying slightly from the published form, bears the date, “Bristol, Sep: 1758,” and appears to be the distillation of this meeting. Contrary to the impression of its published title, the original work was not intended to be used as a means of the spiritual examination of oneself, but an objective means of evaluating the claims of one professing to be made perfect in love.[6] While it expects a believer to be made perfect in love in an instant, it also emphasizes the necessity of growth in grace:

Many consider that “perfect love which casteth out fear” as instantaneous: all grace is so; but what is given in a moment, is enlarged and established by diligence and fidelity. That which is instantaneous in its descent, is perfective in its increase.

This is certain,—too much grace cannot be desired or looked for; and to believe and obey with all the power we have, is the highway to receive all we have not. There is a day of pentecost for believers; a time when the Holy Ghost descends abundantly Happy they who receive most of this perfect love, and of that establishing grace, which may preserve them from such falls and decays as they were before liable to.

Jesus, Lord of all, grant thy purest gifts to every waiting disciple. Enlighten us with the knowledge of thy will, and show us I the mark of the prize of our high calling.” Let us die to all thou art not; and seek thee with our whole heart, till we enjoy the fullness of the purchased Possession. Amen![7]

Wesley’s 1758 August Conference, informal meeting with Fletcher and other preachers in Bristol, and August Conference of 1759 in London were important contributions to Wesley’s understanding of Christian perfection. Works such as “Thoughts upon Christian Perfection” and A Plain Account of Christian Perfection[8] were the fruition of these meetings.

Life as Vicar of Madeley (1760-1785)

I. Instituted as Vicar of Madeley (October 7, 1760)

On October 7th, 1760, Fletcher was instituted to the Madeley parish as vicar at the bishop’s palace. On the 17th, he was inducted at Madeley, and on Sunday the 26th, he began his ministry as vicar.

II. President of Trevecka College (1768-1771)

In the late 1750s, Fletcher became well acquainted the leaders of both the Calvinistic and Wesleyan Methodists. It was through these circles of influence that Fletcher first came into contact with Lady Huntingdon, the patroness of the Calvinistic Methodists. In 1768, Lady Huntingdon engaged Fletcher as the first president of Trevecka College in Wales. This relationship was, however, to be short lived due to the theological controversy which began in 1770.

III. The Minute Controversy (1771-1775)

Controversy with the Calvinists began in 1770 over Wesley’s Minutes of his Conference of that year. In 1771, Fletcher attempted to avert misunderstanding and penned the first of his six Checks to Antinomianism. The controversy lasted for years, pitting Fletcher against Richard and Rowland Hill and Augustus Toplady, to mention only a few of his combatants.

John Fletcher had been part of the Minute Controversy, in support of John Wesley, since July of 1771. The controversy lasted a number of years between the Calvinists and Arminians of the Anglican Church. Finally, in 1775, Fletcher dealt an enormous blow to the Calvinistic anti-perfectionism with his Last Check to Antinomianism.

IV. Recuperation in Switzerland (1777-1781)

In an attempt to recover his health, Fletcher returned to his home in Nyon, Switzerland. Though away from his parish from 1777 to 1781, he remained the vicar of the parish.

V. Marriage to Mary Bosanquet (1781)

Upon returning to England from Switzerland, Fletcher married Mary Bosanquet, someone who he had admired for a number of years. The wedding took place on November 12, 1781 in the parish church at Batley.

VI. Fletcher Dies (1785)

John and Mary Fletcher were married for nearly four years before he passed away on August 14, 1785 in Madeley.

VII. Baptism of Spirit in Portrait of St. Paul (1790)

Fletcher’s Portrait of St. Paul was published posthumously. It was written following the Minute or antinomian controversy of the early 1770s. In order to recover his health, Fletcher returned to his homeland of Switzerland. During his four year stay in Switzerland, he wrote his classic pastoral theology. The Portrait of St. Paul contains some of Fletcher’s most mature thoughts concerning the work of the Spirit in the perfecting of the believer. The baptism of the Holy Spirit, for Fletcher, in its fullest sense refers to the perfecting of the believer in love. The twentieth century Pentecostal movement derives its use of this phrase from those sympathetic to the holiness message at Oberlin. It is likely that the use of this phrase, in America, originated with Fletcher. However, it is the belief of this writer, that Fletcher may have borrowed the phrase from a Quaker in Shropshire, England by the name of Abiah Darby.

VIII. Mary Fletcher Dies (1815)

Mary Fletcher remained in the vicarage following John’s death and maintained a vital Methodist-styled ministry to the people. Thirty years after John’s death, Mary passed away in Madeley.

For a detailed listing of the writings of John and Mary Fletcher, please click to see "John William and Mary Fletcher: A Bibliography."America deserves to know its true heritage.

Please contribute today!

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

* John William Fletcher *

- 3

- 4shares